• Research / Analysis of the human rights situation in Ukraine / Human rights in Ukraine – 2006. Human rights organizations’ report

Human rights in Ukraine – 2006. VII. The Right of access to Information

We would note that the Ministry of Justice did prepare a draft law on amendments and additions to the Law “On information” which was posted on the Ministry’s website for public discussion and also sent to the Council of Europe for comments. Both the public and the Council of Europe were severely critical of the draft law which was then considerably reworked in February – March 2007 with the participation of human rights organizations. However it was not then tabled in parliament as a result of the political crisis.

The preparation and debate over this draft law once again vividly highlighted two conflicting trends with regard to openness from the authorities: the demand from the public to know everything about the activities of the government and its officials pitched against the firm aversion of the latter to openness and wish to conceal their activities. On the other hand, talk about “transparency of governance” has in recent years become popular not only among specialists on access to information and academic circles. These days, all of Ukrainian society is caught up, in different roles, in the “performance: “Information openness: Ukraine: dream and reality”. High-ranking public officials at all of the highest-level international meetings assure the European and world community of their commitment to democratic values and in official speeches they declare a course towards information openness. Yet when members of the public demand that they stop unlawfully classifying information, it transpires that the talk about how it is the government’s direct duty to safeguard the right of access to information was just that – mere words and even those were for international consumption and not for their own community.

While some try to draw up mechanisms for ensuring the right to information, others assert the need for information security of the State above all else, understanding by this totally classifying information about the activity of the authorities. The latter do not understand that in fact such an interpretation of information security is outdated in the modern world. Safeguarding information security as an element of national security means, first and foremost, ensuring the right to know what the authorities are doing since only “wide access to information enables members of the public to form an adequate view and critical assessment of the state of the society which they live in and of the authorities in charge. This encourages people to take an informed part in issues of public importance, fosters greater efficacy and efficiency from administrative agencies and helps to support their integrity and avoid corruption. It is a factor which confirms the legitimacy of the bodies of governance as State services and strengthens public confidence in the authorities”[3].

In 2006 human rights organizations continued training the authorities and bodies of local self-government to adhere to legislation and respond to information requests and letters. These activities are part of a joint project entitled “Access to information about the work of the authorities and bodies of local self-government” begun in 2005. In order to carry out an analysis of the state of play with access to information, the following 19 organizations formed a network: the “Maidan” Alliance; the Podillsk Human Rights Centre (Vinnytsa); the Kirovohrad Association “Civic Initiative”; the children’s environmental organization “Flora” (Kirovohrad); the Odessa, Kherson and Luhansk regional branches of the Committee of Voters of Ukraine; the environmental-humanitarian association “Zeleny svit” [“Green World”] (Chortkiv, Ternopil region); the Ukrainian environmental association “Zeleny svit”; the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group; the Kherson regional youth organization “Youth Centre for Regional Development”; Donetsk Memorial; "Legal Education Centre (Kalush, Ivano-Frankivsk region); the Committee on Monitoring Press Freedom in the Crimea; the East Ukrainian Centre for Civic Initiatives (Luhansk); the International Society for Human Rights – Ukrainian Section; the NGO “For the rights of each of us” (Kremenchug); the Civic Organization “M’ART” (Chernihiv); and the Chernihiv Civic Committee for the Protection of Human Rights. During 2005, 2006 and the first two months of 2007, they sent information requests and appeals to regional authorities and bodies of local self-government with the same previously agreed questions. The letters to the central authorities were sent by the “Maidan” Alliance together with the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group.

The aim of the study was not merely to ascertain the general situation in the country with access to information, but also to identify any trends over recent years towards greater openness among the authorities and bodies of local self-government, as the latter maintain are evident, and to also establish the main reasons and factors at play with violations of the right to information. Analysis of responses to information requests also makes it possible to identify the failings, gaps and clashes in information legislation. The monitoring enabled us to assess the impact of the human factor (the general level of awareness and openness of public officials and civil servants, their level of knowledge of legal regulation regarding access to information, the grounds for limitation). As a result we were able to prepare recommendations for improving the mechanisms of access to information. The project covered the entire network of government agencies and bodies of local self-government. The information requests were sent to the Verkhovna Rada, the Constitutional Court, the High Council of Justice, the President and his Secretariat, the Cabinet of Ministers, central and local authorities, law enforcement agencies, the judiciary and bodies of local self-government. All regions of Ukraine, as well as the Autonomous Republic of the Crimea were covered.

In assessing the general level of availability of information about this or that structure, the following factors were taken into account: 1) the overall number of responses to the information requests; 2) the number of such requests for information actually complied with; 3) the number of refusals to provide the information or document; 4) the number of requests simply not responded to; 5) the substantive nature, fullness and accuracy of the response; and 6) whether the information or document was provided within the stipulated time frame.

We also analyzed the reasons why the recipients refused to provide the information.

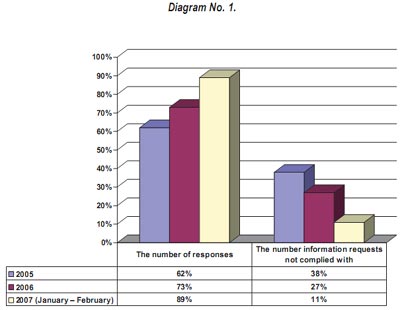

In detail, then, throughout 2005, 2006 and January – February 2007, a total of 1,528 information requests were sent: 376 in 2005; 1,041 in 2006; and 111 in the first two months of 2007. Human rights groups sent 15 information requests to the Verkhovna Rada; 17 to the President and Presidential Secretariat; 15 to the Cabinet of Ministers; 2 to the Constitutional Court; 2 to the Accounting Chamber; 4 to the National Television and Radio Broadcasting Council; 596 to Ministries and State Committees and central executive bodies with special status; 382 requests to local executive offices of territorial agencies of Ministries and State Committees; 149 to local and appellate courts; 89 to prosecutor’s offices; 149 to bodies of local self-government (including the Crimean Parliament and Council of Ministers); 7 to National Deputies (MPS) and 1 request was sent to the Kyiv city directorate of Ukrposhta [the Ukrainian Postal Service].

Overall 604 requests for information were complied with; another 242 were partially met. In 2005 we received 178 responses; in 2006 – 612; and for the first two months of 2007 – 56. These results would seem cause for some optimism and one might even think that at the beginning of 2007, in comparison with 2005, the situation as far as safeguarding the right to information is concerned had improved considerably.

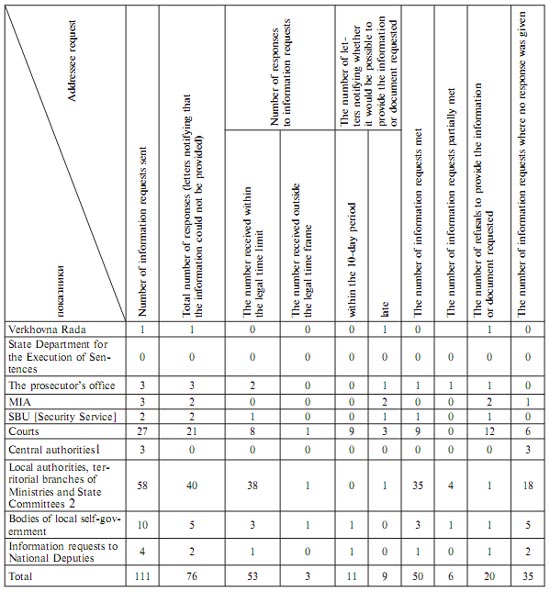

However the fact that in percentage terms the largest number of responses received was at the beginning of 2007 does not, regrettably, indicate that the work of the authorities in Ukraine has become more transparent. On closer analysis of the situation with access to information regarding the work of the authorities a quite different picture begins to emerge. For example, in 2007 not one of the requests for information sent to the Verkhovna Rada, the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) or the central authorities was met. Only 9 responses, against 27 were received from local and appellate courts. National Deputies ignored their electorate with only one response received from 4 requests, while the bodies of the territorial communities disregarded their own communities, with only 4 of the 10 requests sent this year being met. Thus, in January – February 2007 satisfactory results regarding provision of information were received only from the local authorities, with these meeting 67% of the requests. However if one compares this figure with that for 2006, one sees that it has actually fallen by 2 %.

Table summarizing the results for all authorities in January – February 2007

Taking information requests for the entire monitoring period into account (2005- February 2007), we see that the right of access to information via information requests is most often infringed by National Deputies – 71%; the Verkhovna Rada – 67%; prosecutor’s offices – 66%; the President and his Secretariat – 65%; the Security Service (SBU) – 58%; the Cabinet of Ministers – 54%; and the State Department for the Execution of Sentences – 51%.[6]

In 2005 the least forthcoming with information were the Security Service, the appellate and local courts, the prosecutor’s office, and the State Department for the Execution of Sentences. Not one information request was met by SBU. The courts refused to give information in response to 68% of the requests, and simply ignored another 8%. The prosecutor’s office did not meet 74% of the requests sent did not elicit the information. This is despite the laws regulating the work of these bodies all proclaiming that their work is based on the principle of openness (information transparency). These are the laws “On the prosecutor’s office” (Article 6.5; “On the State Department for the Execution of Sentences” (Article 2.8); and “On the Security Service of Ukraine” (Article 3).

However, only the Ministry of Internal Affairs (in comparison with other law enforcement and judicial bodies) in 2005 conscientiously fulfilled its duty to inform the public about its activities. This was in compliance with Article 3 of the Law “On the police” which states that “the activities of the police shall be open. They shall inform civic organizations and the public about their work, about the situation with public order and measures on improving this”.

In 2005 the most forthcoming with information were the central authorities, as well as the Accounting Chamber and the Constitutional Court. Yet by 2006 it had become more difficult to obtain information about the central authorities. And the Accounting Chamber and the single body of constitutional jurisdiction completely refused to provide the information requested.[7] The Constitutional Court, for example, refused to provide information about the number of appeals from individuals or legal entities it had received, as well as information about the number of decisions taken to institute proceedings and the number of refusals to do so. It is the responses to information requests from Ukraine’s Constitutional Court which can serve as a litmus test for the transparency of the entire State mechanism, since it occupies the main position in the mechanism for protecting the rights of the individual, including his or her right to information. The question necessarily arises, therefore: if the single body of constitutional jurisdiction in Ukraine, whose main task is to guarantee the primacy of the Constitution as the Main Law of the land over all Ukrainian territory refuses to adhere to the Constitution and safeguard the right to information enshrined therein, can one expect other government institutions to not violate this fundamental right?

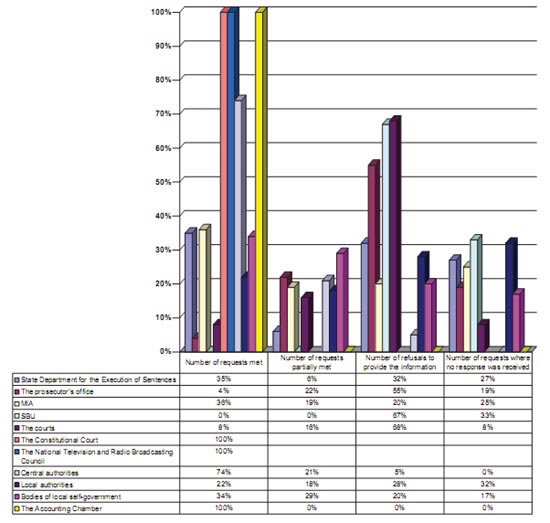

One can point to a positive trend in 2006 in the number of proper responses to information requests addressed to law enforcement and judicial bodies. In the ratings as far as being open with information is concerned, top place was taken by the judiciary, second in terms of requests met went to local authorities, while the National Television and Radio Broadcasting Council took third place.[8] .

Table showing the level in percentages of compliance by the authorities and bodies of local self-government with information requests, 2005-2007 (January-February).

| Recipient | Number of requests met | Number of requests partially met | Number of refusals to provide the information

| Number of requests where no response was received |

| Verkhovna Rada | 33% | 0% | 7% | 60% |

| National Deputies | 29% | 0% | 29% | 42% |

| The President and the Presidential Secretariat | 29% | 6% | 6% | 59% |

| Cabinet of Ministers | 33% | 13% | 47% | 7% |

| Constitutional Court | 50% | 0% | 50% | 0% |

| Accounting Chamber | 50% | 0% | 50% | 0% |

| National Television and Radio Broadcasting Council | 75% | 0% | 25% | 0% |

| Central authorities | 55% | 9% | 21% | 15% |

| Local authorities and territorial branches of ministries and State departments | 40% | 21% | 18% | 21% |

| The courts | 45% | 12% | 34% | 9% |

| The prosecutor’s office | 22% | 12% | 57% | 9% |

| SBU | 28% | 14% | 44% | 14% |

| MIA | 42% | 19% | 28% | 11% |

| The State Department for the Execution of Sentences | 42% | 7% | 26% | 25% |

| Bodies of local self-government | 32% | 28% | 21% | 19% |

Graph showing the information requests met in 2005

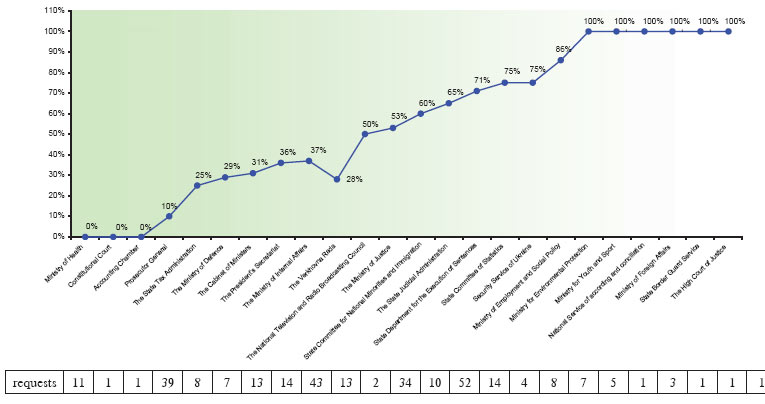

Graph showing the number of proper responses from high-level government offices and central authorities as a percentage of the number of information requests (2006).

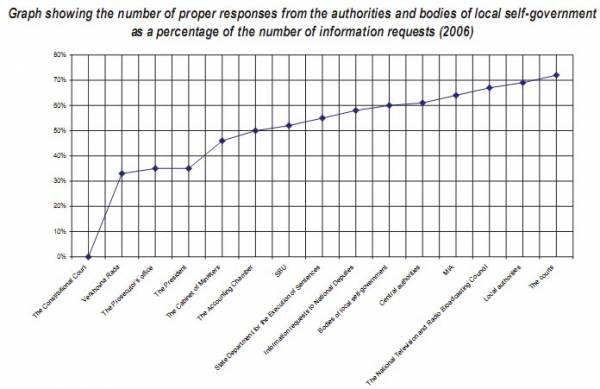

Graph showing the number of proper responses from the authorities and bodies of local self-government as a percentage of the number of information requests (2006)

A request shall be met within a month, unless otherwise provided by law. (Article 33 of the Law “On information”)

Given the specific nature of information, the fact that it spoils quicker than milk left in the sun, it is not only important whether a request is met, but also how quickly the information or document is provided. During the entire project 677 responses were provided in the time stipulated by law, this meaning that 169 responses were late. On average they came 2 – 3 weeks late, although there were occasions where the period reached three months. For example, the National Television and Radio Broadcasting Council responded to a request from 11 August 2006 near the New Year, on 14 December, despite there being no objective grounds for such a delay. The said Council had been asked for information about the number of licensed television and radio organizations. Incidentally, “notification of postponement in meeting a request when the period for providing the information exceeds the legally established period” throughout the entire monitoring only came a few times. We can thus state that the norm binding the authorities in case pf postponement to inform the person requesting the information in written form (Article 24 of the Law “On Information” is hollow.

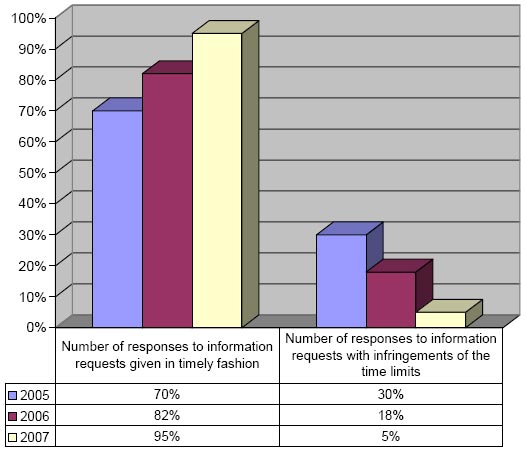

In general with each year the authorities become better at providing the information requested within the time limits.

Diagram No. 2

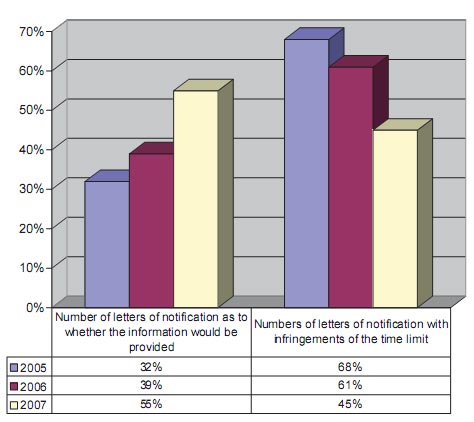

The monitoring showed that public officials and civil servants systematically infringe Article 33. § 1.2 of the Law “On Information” which states that “The terms for addressing such request shall not exceed ten calendar days[9]. During this period a State body shall inform in writing the requestor that his/her request will be addressed or that the document required cannot be disclosed”. The project researchers gained the impression that the authorities and bodies of local self-government refused to meet a request precisely in the time frame stipulated by law for meeting a request, i.e. within a month, and that they were not aware of the 10-day limit for notifying that a request would not be met. Furthermore, the authorities ignore the requirement to send notification that the “request is being processed and the information sought will be provided within the established period”. During the monitoring we received no more than twenty such letters. There were also oddities as when the notification that the information would be provided arrived, but the information never appeared.

Diagram No. 3

Do public officials and civil servants not know which law regulates procedure for issuing information?!

From processing the responses which arrived from the authorities or bodies of local self-government, it became clear that public officials and civil servants do not know which law regulates procedure for responding to information requests. For example, the SBU Division in the Kirovohrad region, in giving reasons why it could not provide the information, referred to Article 5 of the Law “On citizens’ petitions”, a “written petition must be signed by the petitioner with the date indicated. A petition which does not comply with this shall be returned to the petitioner”. However, the petition was, firstly, prepared correctly with the signature of the petitioner and the date, and, secondly, the Law “On citizens’ petitions” is not aimed at exercising the right to information (Article 34 of the Constitution), but the right to file individual or collective petitions (Article 40 of the Constitution), and this is, by its juridical nature, a different right. The Law “On citizens’ petitions” regulates the exercising in practice by members of the public of their right as set down in the Constitution to submit to the authorities or civic organizations in accordance with their charter proposals on improving their activities, to identify shortcomings in their work, appeal against the actions of public officials, government or public agencies. The Law ensures that Ukrainian citizens have the opportunity to take part in governance of State and public matters, to contribute to an improvement in the work of the authorities and bodies of local self-government, enterprises, institutions and organizations regardless of their form of ownership, in order to uphold their rights and legitimate interests and to reinstate these should they have been infringed. According to Article 1 of this Law petitions should be understood as meaning verbal or written proposals (comments), applications (petitions) and complaints.[10] The procedure for receiving information by submitting an information request is regulated by the Law “On information”, in particular Articles 32-37. Further proof that civil servants do not see a difference between the right to information and the right of petition can be found in the response from the Kaluha City Council Executive Committee in the Ivano-Frankivsk region.[11]. Instead of information “where there are internal instructions on the procedure for information requests”, the Executive Committee provided information about the procedure for citizens’ petitions.

The fact that public officials and civil servants in considered information requests to the authorities or bodies of local self-government apply the Law “On citizens’ petitions” is, regrettably, proof of the low level of professional training of Ukrainian lawyers and the fact that the authorities and bodies of local self-government lack specialists on working with information requests regarding access to official documents and requests for written or verbal information.

What a ping pong has in common with an information request

On 9 September 2006 the Prosecutor General was sent an information request seeking the number of established cases where the time limits for administrative detention have been exceeded and information about the reaction to such cases. Instead of the information expected, the Prosecutor General’s office notified that the request had been passed on to the State Committee of Statistics since the reporting by prosecutor’s offices does not envisage the information sought. In its turn the State Committee of Statistics refused to provide the information due to the lack of the data requested. The latter’s response stated: “The State Committee cannot agree with the Prosecutor General’s office having redirected your information request to it from 09.09.2006 and notifies of the following. Since 1995 State Statistics agencies have implemented State statistical observation in accordance with form 1-AP “report on the examination of cases on administrative offences and administrative charges against individuals” (Order of the State Committee of Statistics from 19.10.95 №266). The main aim of this observation is to collect information regarding established cases involving administrative offences. At the same time, your letter raises the question of ensuring the rules for proceedings into administrative offences which in accordance with Article 250 of the Code of Administrative Offences is part of the prosecutor’s office ’supervision which is carried out by prosecutors or their deputies. Detected cases of such violations, for example, as regards exceeding the time limit for administrative detention and the results of responses to these cases can be establishing only from the documents of a prosecutor’s check. The State Committee of Statistics does not, therefore, have the information to provide an answer to your request”.

From this text one can conclude that a vicious cycle has emerged and there is no way of receiving information regarding the number of established cases where the time limits for administrative detention have been exceeded and information about the reaction to such cases Since neither the Prosecutor General’s office nor the State Committee of Statistics deem it necessary to record cases where a fundamental human and civil right – to freedom and personal inviolability (Article 29 of the Constitution) has been violated. This prompts one to think that either the Prosecutor General’s office does not wish to provide the information requested, or the prosecutor’s office is generally not fulfilling in proper manner its overseeing functions linked with the observance of the law as regards administrative detention. .

The information requested is confidential?!

The Kherson regional youth organization “Youth Centre for Regional Development” approached the Kherson Regional Council and the Henichesk District Council of the Kherson region asking for a list of their deputes (their last name, first name and patronymic, date of birth, place of work when elected deputy, what party faction they were voted in on, party affiliation, which faction they actually joined, date and reason for relinquishing their mandate early). However the request was turned down because the addressees deemed this information to be confidential. Such refusals to provide information are not only grave infringements of the right of access to information, they are also patently absurd. Regional and district councils are bodies of local self-government which represent the common interests of territorial communities and not their own interests (Article 10 of the Law “On the status of National Deputies”). It is incomprehensible how individuals who represent the interests of a territorial community can remain unknown to the latter. Even a person not up on the law understands that information about the makeup of the deputy corps, including names, cannot be confidential. Nor was it deemed confidential by the deputies themselves and the media during and after the election campaign. Furthermore, Article 36.8 of the Law “On the election of deputies of the parliament of the Autonomous Republic of the Crimea, local councils, and village, settlement and city mayors”, one of the conditions for registering candidates for the office of deputy in multi-mandate districts is the person’s consent to biographical information being made public.

How much information costs

Two information requests sent in October and November 2006 to the Kakhovske City Council by the Youth Centre for Regional Development failed to elicit the information expected, but instead a letter from the Executive Committee asking them to pay 3 thousand UAH for it, without giving any reason whatsoever for the charge. The director of the Centre M.V. Honchar correctly notes that according to Article 36 of the Law “On information” “The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine or other state institutions shall determine payment procedures and fees for the collection, search, preparation, creation, and supply of requested written information, provided the said fees do not exceed the expenses actually entailed to meet such requests”, while Articles 35 and 36 of the Law only directly mention fees for copying documents. The Executive Committee overcharged for such services.

Can naming an alternative source where the information can be found be regarded as meeting the request for information?

A common reason given for not providing the information is that the information can be found elsewhere. Firstly, however, the right of access to information can be exercised in different ways, and the fact that bodies of local self-government are obliged to publish information about their activities through official publications, on their websites, and so forth (passive access) does not absolve them of the duty to provide information via formal requests for information. Secondly, even if one allows that it may be possible to meet a request for information when, instead of actually providing the said information, a place where it can be found or an official document is named, the response must give not only the name of the sources, but also if it is a particular body’s official publication the number, year and pages where the information or document can be found. In cases where a website is suggested as source, the specific address should be given. Otherwise obtaining the information from the other source will be problematic, if not actually impossible.

For example, in a response from 07.11.06 No. 205/3 to a request from 25.09.06 “to provide information about the yearly budget and how it was applied”, the Odessa City Council replied that the information requested had been published in the Council’s newspaper “Odessa Herald” and on its official website (www.city.odessa.ua). However it did not indicate in which specific issues of the newspaper the budget and information about its use had been published. Moreover, the website address was wrong and the information was available on the information site of the city at: http://misto.odessa.ua/ , and given the lack of number or date of the resolution (adopting the budget), finding it among the 164 resolutions in 2006 on the site was a fairly difficult task. It was even harder to find information about how the budget had been spent.

One can also cite the refusal to provide information requested which came from the Nova Kakhovka City Council. The refusal was justified on the grounds that “the information requested is constantly published in the newspaper “Nova Kakhovka” and other local publications”.

We are convinced that one cannot regard a request for information to have been complied with if an alternative source is given instead of the actual information. The draft law “On information” prepared by the Ministry of Justice does in fact state that “an information request is considered to have been met by the holder of the information who received the request, if the information can be obtained from another source without difficulty and quickly, and the requestor is informed of this”. We believe, however, that this norm should be withdrawn from the draft law since it gives a formal excuse for executive bodies to avoid providing information and could thus undermine such an extremely important means of access to information as information requests. Furthermore, given that a considerable part of Ukraine’s population lives in rural areas or small towns, in many of which there are no libraries holding these official publications, the local authorities do not have special premises or simply places where those requesting information can work with the documents, and there simply is no access to the Internet, the inclusion of such a norm in the law would adversely affect access to information in Ukraine.

The information requested cannot be provided since …

Most of the letters informing of a refusal to provide the information requested began with this phrase or variations on it. With regard to grounds given for not providing the information, the project participants were particularly disturbed by the fact that the addresses refused to provide information which is on open access, and the grounds given did not comply with Article 34 of the Constitution, and infringe the constitutional right of access to information.

Among the reasons given by prosecutor’s offices for not providing information requested are the following gems:

· It is not within the jurisdiction of the Svitlovodsk inter-district prosecutor’s office (Kirovohrad region) to provide information to legal entities in order for them to carry out programmes supported by foreign governments.

· The Prosecutor’s offices are not part of the legislative, executive or judicial branches of power and therefore are not obliged to provide information in response to the requests set out in Article 32 of the Law “On information” [access to official documents].

· In accordance with Article 9 “Every citizen shall be ensured free access to information relating to that citizen, except in cases envisaged by the laws of Ukraine”. At the same time, from the content of your letter, it is not clear which specific rights, liberties and legitimate interests the organization which you hear needs the information requested to exercise, or how the information concerns you personally. Therefore your right as a citizen and as the head of the Odessa Regional Branch of the Committee of Voters of Ukraine to receive the information has not been confirmed. Due to this there are no legitimate grounds for providing the information. The issuing of expert assessments to citizens is not foreseen by current legislation.

· This information is provided only to high-level bodies of the prosecutor’s office.

Some explanations from the prosecutor’s office are capable of both depressing and arousing mirth. As mentioned earlier, the prosecutor’s office quite often refuses to meet information requests because it is not part of any branch of power. If one follows their line o f thinking further, one could come to the conclusion that the prosecutor’s office is not a body of State power since according to Article 6 of the Constitution “State power in Ukraine is exercised on the principles of its division into legislative, executive and judicial power”. So, dear citizens, if you, God forbid, are summoned to the prosecutor’s office, you can legitimately turn down this “invitation” since the prosecutor’s office does not belong to any branch of power.

The same prosecutor’s office has also refused to provide information or documents on the following grounds:

· Due to the fact that these figures are not foreseen in statistical reporting;

· Due to the lack of such information

· The information is confidential;

· The information is on restricted access[12];

· Documents are not provided on the basis of Article 37.5 of the Law “On information” ;

· In accordance with Article 37 of the Law “On information”», the information requested is not subject to compulsory access to official documents as per request;

· The information sought is information about operational or investigative work of prosecutor’s offices and its disclosure could jeopardize operational measures, intelligence or detective work into criminal cases.

In some cases no grounds whatsoever are given for the failure to provide part of the information.

It is interesting that the same information was on some occasions provided and on others withheld for different reasons. Law enforcement agencies, furthermore, are reluctant to provide copies of documents.

The most common reason for not providing information given by divisions of SBU was that the information requested was on restricted access, for example:

1. According to SBU Order No. 245/DSK[13] from 05.11.1999 the statistical data which you have asked for is confidential information;

2. According to Articles 30 and 37 of the Law “On information” the information is on restricted access;

3. Reference to the Cabinet of Ministers Resolution from 27.11.1998 No. 1893 “On approving instructions for the registration, storage and use of documents, cases, publications and other material forms of information containing confidential information held by the State”;

4 Pursuant to Article 20 of the Law “On information” the information and documents which you ask us to send are nor for mass information and cannot therefore be provided.

The MIA refused to provide information on two main grounds: a) because they didn’t have the information requested and b) the information was on restricted access.

Divisions of the State Department for the Execution of Sentences explained their refusals to provide information in the following ways:

1. The information is internal documentation (divisions of the Crimea, the Donetsk, Zhytomyr and Odessa regions);

2. To receive the necessary information the requestor must agree the issue with the State Department for the Execution of Sentences (divisions of the Ivano-Frankivsk and Rivne regions);

3. The regional nature of the activities of the organization (State Department for the Execution of Sentences);

4. The information can only be provided with the consent of the State Department for the Execution of Sentences (Zhytomyr region division);

5. A rather interesting explanation was given by the Donetsk regional division of the State Department. We give their text in full:

«In compliance with Article 40 of the Constitution we would inform you that the information which you have asked for on the activities of the Donetsk regional division of the State Department, pursuant to Article 38 of the Law “On information” is the property of the Department and of the State. The grounds for the right of ownership of this information are the creation of the given information by the Division and at State expense. In accordance with current legislation “The owner of information shall have the right to appoint a person to possess, use and dispose of this information, as well as to determine the rules of processing these data and access thereto, along with determination of other terms and conditions relating thereto». It has been established as a result of the response received that the project you are carrying out is nongovernmental. As a result of this a copy of this project was not presented. We were thus prevented from familiarizing ourselves and studying the given project to check its compliance with current legislation. One can also assume that the given project is aimed at collecting information which according to Article 37 of the Law “On information” is restricted information”.

We thus see that among the listed reasons, there is not one legal argument entitling the State Department for the Execution of Sentences to refuse to provide the information requested.

The central authorities had a very simple way of explaining their refusal to provide information – they said that they didn’t have it. And the State Committee on Nationalities and Migration and the State Department on Religious Affairs, rather than responding to the information requests, sent letters with advice to find the information which the requestor was seeking on their official websites.

Judges explained their refusals to provide information in the following ways: by claiming that the information was secret or confidential (19 refusals); saying that statistical data was not available (14 refusals); due to technical impossibility (3 refusals); claiming the need to provide confirmation of the authority of the person making the request (1 refusal). 13% of the letters refusing to provide the information did not give any reason at all.

Bodies of local self-government gave the following explanations for not giving the information:

1. lack of data;;

2. technical impossibility of providing the necessary amount of information;

3. That on the basis of Article 8 of the Law “On information” the information demanded is not one of the “Objects of Information Relationships” which the Law covers and which citizens have the right to receive (Kherson City Council);

4. the information is on restricted access;

5. the need to pay 3 thousand UAH for the information.

Analyzing the grounds on which the public authorities and bodies of local self-government refuse to provide the information requested, we established that one of the reasons for unwarranted restriction (that is, violation) of the right of access to information is flawed legislation in this area. For example, according to Article 37 of the Law “On information” “Compulsory access to official documents as per request shall not apply to documents containing: information not to be disclosed pursuant to other legislative or normative acts”. However Article 34 § 3 of the Constitution stipulates that the exercise of these rights may only be restricted by law. Article 37.7 of the Law is therefore not in line with the Constitution. One should note that it is specifically on the basis of Article 37.7 that law enforcement agencies and the State Tax Inspectorate refused to provide information on request.

The Odessa State Tax Inspectorate [STI] for example justified its refusal to provide information about the number of checks of people involved in business activities, as well as information about whether there is internal procedure for bringing proceedings against personnel of tax offices or the tax police for violations of the law by referring to Article 37.7 of the Law “On information”. On the basis of this norm in the Law, the Inspectorate cited Regulations on tax information in the State Tax Service, approved by Order of the STI from 02.04.1999 No. 175 “On approving Regulations on tax information in the State Tax Service of Ukraine”, according to which the given information may not be provided. It is interesting that the actual Regulations No. 175 were not published, meaning that in accordance with Article 57 of the Constitution, the given Regulations are not valid at all. The State Tax Inspectorate does not have the right on the basis of these Regulations to refuse to provide information. Yet even were the STI to publish the Order, it would still run counter to Article 34 of the Constitution.

Table summarizing the results for all bodies of power, 2005

Addressee

Number of information requests sent

Overall number of responses (letters of notification saying that the information could not be provided)

Number of responses to information requests received

Number of replies received on time

Number of replies received late

Number of letters notifying whether the information could be provided

Within the ten-day time limit

Late

The number of information requests met

The number of information requests partially met

The number of refusals to provide the information

The number of information requests which received no answer

ПО-МОЕМУ, ВЕЗДЕ ОДИНАКОВО – ЕСЛИ НЕТ, ТО ПИШИТЕ

|

показники Адресат Запиту | кількість надісланих запитів | Загальна кількість відповідей (повідомлення Про не можливість задоволення інформаційного запиту

|

кількість відповідей на інформаційний запит

| Кількість повідомлень запитувача щодо можливості надати запитувану інформацію чи документ | Кількість задоволених запитів | Кількість частково задоволених запитів | Кількість відмов в задоволенні запиту

| кількість запитів залишених без відповіді | ||

| кількість своєчасно отриманих відповідей на інформаційні запити | кількість відповідей на інформаційний запит з порушенням строку | у 10 денний термін | з порушенням терміну | |||||||

| State Department for the Execution of Sentences | 63 | 46 | 23 | 3 | 9 | 11 | 22 | 4 | 20 | 17 |

| Prosecutor’s Office | 27 | 22 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 15 | 5 |

| MIA | 64 | 48 | 21 | 14 | 2 | 11 | 23 | 12 | 13 | 16 |

| SBU | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| The courts | 25 | 23 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 13 | 2 | 4 | 17 | 2 |

| The Constitutional Court | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The National Television and Radio Broadcasting Council | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| The central authorities [14] | 19 | 19 | 11 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| The local authorities and territorial offices of ministries and State departments[15] | 104 | 71 | 29 | 13 | 12 | 20 | 23 | 19 | 29 | 33 |

| Bodies of local self-government | 65 | 54 | 26 | 15 | 4 | 11 | 22 | 19 | 13 | 11 |

| The Accounting Chamber | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 376 | 290 | 125 | 53 | 37 | 80 | 110 | 68 | 112 | 86 |

Table summarizing the results for all bodies of power, 2006

|

Адресат Показники Запиту | Кількість надісланих запитів | Загальна кількість відповідей (повідомлення Про не можливість задоволення інформаційного запиту

|

кількість відповідей на інформаційний запит

| Кількість повідомлень запитувача щодо можливості надати запитувану інформацію чи документ | Кількість задоволених запитів | Кількість частково задоволених запитів | Кількість відмов в задоволенні запиту

| Кількість запитів залишених без відповіді | ||

| Кількість своєчасно отриманих відповідей на інформаційні запити

| Кількість відповідей на інформаційний запит з порушенням строку | у 10 денний термін | з порушенням терміну | |||||||

| State Department for the Execution of Sentences | 63 | 48 | 30 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 30 | 5 | 13 | 15 |

| Prosecutor’s Office | 159 | 147 | 47 | 9 | 41 | 50 | 40 | 16 | 91 | 12 |

| MIA | 179 | 168 | 86 | 28 | 13 | 45 | 80 | 34 | 54 | 11 |

| SBU | 21 | 19 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 2 |

| The courts | 97 | 92 | 66 | 4 | 11 | 13 | 56 | 14 | 22 | 5 |

| The central authorities [16] | 173 | 146 | 86 | 21 | 17 | 22 | 94 | 13 | 39 | 27 |

| The local authorities and territorial offices of ministries and State departments [17] | 220 | 192 | 128 | 25 | 23 | 23 | 96 | 57 | 39 | 28 |

| Bodies of local self-government | 74 | 62 | 29 | 15 | 11 | 14 | 22 | 22 | 18 | 12 |

| The Verkhovna Rada | 14 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| The President and President’s Secretariat | 17 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| The Cabinet of Ministers | 15 | 14 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 1 |

| The National Television and Radio Broadcasting Council | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| The Constitutional Court | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| The Accounting Chamber | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Information requests to National Deputies | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| The Kyiv City Directorate of the Ukrainian Postal Service | 1 | 1 | 1

| 0

| 0

| 0

| 1

| 0

| 0

| 0

|

| Total | 1041 | 908 | 499 | 113 | 124 | 192 | 444 | 168 | 296 | 133 |

Table summarizing the results for all bodies of power – January – February 2007

|

Адресат запиту Показники

| Кількість надісланих запитів | Загальна кількість відповідей (повідомлення Про не можливість задоволення інформаційного запиту

|

кількість відповідей на інформаційний запит

| Кількість повідомлень запитувача щодо можливості надати запитувану інформацію чи документ | Кількість задоволених запитів | Кількість частково задоволених запитів | Кількість відмов в задоволенні запиту

| Кількість запитів залишених без відповіді | ||

| Кількість своєчасно отриманих відповідей на інформаційні запити

| Кількість відповідей на інформаційний запит з порушенням строку | у 10 денний термін | з порушенням терміну | |||||||

| The Verkhovna Rada | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| State Department for the Execution of Sentences | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Prosecutor’s Office | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| MIA | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| SBU | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| The courts | 27 | 21 | 8 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 0 | 12 | 6 |

| The central authorities | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| The local authorities and territorial offices of ministries and State departments[18] | 58 | 40 | 38 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 35 | 4 | 1 | 18 |

| Bodies of local self-government | 10 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Information requests to National Deputies | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 111 | 76 | 53 | 3 | 11 | 9 | 50 | 6 | 20 | 35 |

Table summarizing the results for all bodies of power

|

Адресат запиту показники

| кількість надісланих запитів | Загальна кількість відповідей (повідомлення Про не можливість задоволення інформаційного запиту

|

кількість відповідей на інформаційний запит

| Кількість повідомлень запитувача щодо можливості надати запитувану інформацію чи документ | Кількість задоволених запитів | Кількість частково задоволених запитів | Кількість відмов в задоволенні запиту

| кількість запитів залишених без відповіді | ||

| кількість своєчасно отриманих відповідей на інформаційні запити | кількість відповідей на інформаційний запит з порушенням строку | у 10 денний термін | з порушенням терміну | |||||||

| State Department for the Execution of Sentences | 126 | 94 | 53 | 8 | 12 | 21 | 52 | 9 | 33 | 32 |

| Prosecutor’s Office | 189 | 172 | 55 | 10 | 46 | 61 | 42 | 23 | 107 | 17 |

| MIA | 246 | 218 | 107 | 42 | 15 | 58 | 103 | 46 | 69 | 28 |

| SBU | 29 | 25 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 13 | 4 |

| The courts | 149 | 136 | 80 | 5 | 23 | 29 | 67 | 18 | 51 | 13 |

| The central authorities | 195 | 165 | 97 | 28 | 17 | 23 | 108 | 17 | 40 | 30 |

| The local authorities and territorial offices of ministries and State departments [19] | 382 | 303 | 195 | 39 | 35 | 44 | 154 | 80 | 69 | 79 |

| Bodies of local self-government | 149 | 121 | 58 | 31 | 16 | 25 | 47 | 42 | 32 | 28 |

| The Verkhovna Rada | 15 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| The President and President’s Secretariat | 17 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| The Cabinet of Ministers | 15 | 14 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 1 |

| The National Television and Radio Broadcasting Council | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| The Constitutional Court | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| The Accounting Chamber | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Information requests to National Deputies | 7

| 4

| 1

| 1

| 1

| 1

| 2

| 0

| 2

| 3

|

| The Kyiv City Directorate of the Ukrainian Postal Service | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 1528 | 1274 | 677 | 169 | 172 | 281 | 604 | 242 | 428 | 254 |

Conclusions

In summarizing the results above, the following conclusions would seem warranted.

1. At present in Ukraine the right of access to information is merely declared, yet not guaranteed.

2. Public officials and civil servants treat information as their own property (despite the fact that it is prepared at the taxpayer’s expense).

3. Public officials and civil servants regularly breach the time frames stipulated for information requests, especially as regards the period for informing that an information request cannot be met.

4. The norm of Article 34 of the Law “On information” which obliges the authorities where provision of information as per request is to be postponed to notify the requestor of this in writing with an explanation of how to appeal against this decision is not complied with at all.

5. Infringements of the right to information are of a systemic nature and provision of the information or official documents requested in full and within the stipulated time frames are rather the exception than the rule. Movement therefore towards greater openness as regards information is not significant and it would be too early to speak of any significant changes.

The main reasons for lack of openness from the authorities with respect to information are, in our opinion, the following:

1. The low level of professional training of public officials and civil servants.

2. Lack of knowledge of information legislation.

3. The inability of public officials and civil servants to correctly interpret the norms of the law which results in their faulty understanding of both the letter and the spirit of the Constitution and laws of Ukraine.

4. The lack of a mentality based on information openness among the authorities “as the result of a legacy of a State “of great illusions and rotten morality”

5 The absence of proper legal regulation in the area of access to information, with the Law “On information” and other normative legal acts having significant shortcomings and not complying with international standards for freedom of information.

6. It should be noted that the failure to provide information because it is deemed to be confidential on the basis of Articles 30 and 37 of the Law “On information”, as has already been stressed on many occasions, is unwarranted since the above-mentioned norms do not comply with the Constitution nor with international standards in this sphere. We would furthermore draw attention to the fact that the list of items of information with the stamp restricting access “For official use only” [DSK] but which do not constitute State secrets, if they are compiled are not always made public. One thus has the paradoxical situation where we do not have access to official documents providing a list of items of information which are confidential, in other words, we can’t know what it is that we are not supposed to know.

[1] Prepared by the head of the UHHRU Board and co-chair of KHPG Yevhen Zakharov, PhD student in constitutional law at the Yaroslav Mudry National Law University Oksana Nesterenko and legal adviser to the “Maidan” website Oleksandr Severyn.

[2] „Human Rights in Ukraine – 2004, Kharkiv. Folio, 2005, Human Rights in Ukraine – 2005. Kharkiv. Folio, 2005. These are available in English and Ukrainian at the UHHRU site: www.helsinki.org.ua and that of KHPG www.khpg.org .

[3] Freedom of information and the right to privacy in Ukraine. V.1: Access to information: hic et nunc! / Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Kharkiv. Folio, 2004

[4] Not including the law enforcement agencies and the Department for the Execution of Sentences

[5] Not including the law enforcement agencies and the Department for the Execution of Sentences

[6] See the table: Level of compliance by the authorities and bodies of local self-government with information requests in percentages..

[7] See the graph on the number of proper responses from high-level government offices and central authorities as a percentage of the number of information requests (2006).

[8] See the graph showing the number of proper responses from the authorities and bodies of local self-government as a percentage of the number of information requests (2006).

[9] See Diagram No. 3

[10] Article 3, § 2, 3, 4 of the Law “On citizens’ petitions”: “Proposals (comments) are citizens’ petitions which express advice, recommendations on the activity of the authorities or bodies of local self-government, deputies at all levels, public officials; and also present opinions on regulation of public relations and living conditions for citizens, improvement of the legal foundations of State and civic life, socio-cultural and other spheres of activity of the State and society.

An application (petition) is an appeal from citizens seeking the exercise of their rights and interests as enshrined in the Constitution and current legislation, or notification of a violation of current legislation or shortcomings in the functioning of enterprises, institutions and organizations regardless of their form of ownership, of National Deputies, deputies of local councils, public officials, as well as expressing an opinion regarding improvement of their work. A petition is an appeal in writing requesting recognition of the relevant status, rights and liberties, etc.

A complaint is an appeal demanding restoration of the rights and protection of the legitimate interests of citizens violation through the actions (omissions) or decisions of government bodies or bodies of local self-government, enterprises

[11]Response from 26.10.06 to an information request from 29.09.06

[12] Although the information requested was that categorized as being on open access

[13] DSK means for official use only [translator]]

[14] Not including the law enforcement agencies and the Department for the Execution of Sentences

[15] Not including the law enforcement agencies and the Department for the Execution of Sentences

[16] Not including the law enforcement agencies and the Department for the Execution of Sentences

[17] Not including the law enforcement agencies and the Department for the Execution of Sentences

[18] Not including the law enforcement agencies and the Department for the Execution of Sentences

[19] Not including the law enforcement agencies and the Department for the Execution of Sentences