Death brought to Donetsk under a Russian Flag

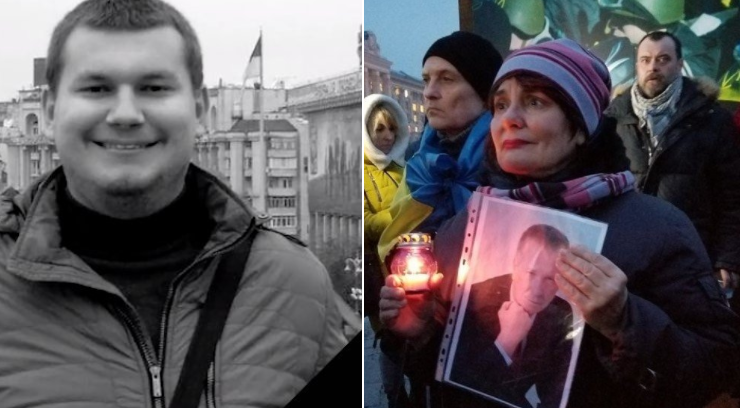

Ukrainians gathered in Kyiv on March 13 to remember the first victim of Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine in Donbas, and all other civilians killed during the senseless conflict. Many of those present had themselves been forced into exile or fled for their lives after Russian and Russian-backed militants seized control in March – April 2014.

Dmytro Cherniavsky was just 22 when he was knifed to death by Russian or pro-Russian protesters who broke through a police cordon in the centre of Donetsk. The young man, who was spokesperson for the Donetsk oblast branch of the VO Svoboda party, had been one of around 100 Self-Defence activists at a peaceful demonstration in support of Ukrainian unity. In contrast to the earlier rallies, especially that on March 5, pro-unity demonstrators were outnumbered by a parallel rally calling for the Donetsk oblast to be joined to the Russian Federation.

According to Artur Shevtsov, who was in Self-Defence with Dmytro, the trouble began after the end of the pro-unity rally. He, Pastor Sergey Kosyak and many others who were present that day all confirm that this was no ‘brawl’, but an attack by the pro-Russian demonstrators on anyone with a Ukrainian flag, orange tape, identifying them as Self-Defence, etc. The police finally yelled to the Self-Defence activists to get into the three police buses, so that they could get them out. This, Shevtsov said, had worked on 5 March, but this time did not, with the pro-Russian activists not backing off enough to get the men to safety.

Shevtsov is convinced that the attack had been planned in advance, and that the majority of the pro-Russian activists were in fact Russians who had been brought in across the border. He says that they stood out because of their accent, their watches which were set to Russian time and also the fact that they didn’t know the way to Lenin Square.

Many people who observed the attempt to seize control in Kharkiv, and the successful seizure of power in Sloviansk and Kramatorsk, have also said that they were sure that the people involved in the seizure were, at least, not local. There were even moments which, in less grave situations, would have been comical, such as when the ‘tourists’, as they were called, from Russia got mixed up and tried to seize the Kharkiv Opera Theatre, mistaking it for the Town Hall.

Father Sergey Kosyak was one of the organizers of the Prayer Marathon in which people of different faiths met together in the centre of Donetsk under the Ukrainian flag to pray for peace and unity. Recalling that first bloodshed four years later, he says that it took place on what was the 17th day of the Prayer Marathon. Unlike the 10 thousand-strong rally for Ukraine on 5 March, this demonstration had not been well-organized, and attracted a much smaller number. With only around 100 Self-Defence activists, they were out-flanked by the Russian and pro-Russian demonstrators who called themselves ‘anti-fascists’. .

There were already several people lying on the ground motionless, he recalls, and these so-called ‘anti-fascists’ kept kicking them and hitting them with sticks. He stepped forward and told them to stop: “You’ve just killed a person, leave those who are lying on the asphalt. I’m a priest, show at least that modicum of sympathy.”. They did stop beating those lying on the ground, he says.

He and others began lifting the injured into an ambulance. Later, standing on Lenin Square, he saw the body of Dmytro Cherniavsky being placed in another ambulance. There was a crowd of people around the statue of Lenin who were giving interviews to people with video cameras.

He was sickened when he understood what was going on. These were Russian TV channels, and he heard one pro-Russian “stand and cry to the journalists about how they’d been peacefully standing and how out of the blue they’d been attacked by pro-Ukrainian activists whom they had to courageous fight off”.

Exactly the opposite of what had, in fact, been the case, he continues, and it was these lies that were fed to Russian viewers.

It was only a few weeks before well-armed fighters under former Russian military intelligence officer Igor Girkin (Strelkov) seized control of Sloviansk and, soon, of other parts of the Donetsk oblast. In absolutely every newly seized city, one of the first things the fighters did was to cut off all Ukrainian media, replacing them with pro-Russian or Russian state-controlled channels. The lies and propaganda on such channels were toxic and very dangerous (examples here and here, with the blood on their hands acknowledged later by some Russian journalists).

Sergey Kosyak says that such “long-term and lying propaganda in Donetsk achieved its end, with many Donetsk people, incited by Russian nationalists who were ferried in their hundreds into our region, to view with hatred those who stand for Ukrainian unity,”

The effect of anti-Ukrainian propaganda was also observed by a human rights mission, with representatives from the Kharkiv Human Rights Group, Russian and German human rights groups. Over the last 3 months of 2014, it made several visits to cities which had been under ‘DNR’ control, including Sloviansk and Kramatorsk during the last three months of 2014.

They found that after months when the Kremlin-backed militants had done everything to scare the population with reports of ‘punitive Ukrainian forces’, people had awaited the Ukrainian armed forces with great trepidation.

“The residents of Krasny Lyman, the city liberated first on June 4 recounted how they had awaited with terror ‘purges’; arrests; repression from the Ukrainian armed forces. However the ‘purge’ was confined to a simple viewing of flats, without even checking documents, and the first day of Sloviansk’s liberation began with free sausages being handed out. There were no reports later either of repression against the local population in liberated cities.”

Except, one assumes, on Russian state-controlled television.