Freed Ukrainian POWs collect money for Russian activist Konstantin Kotov who helped them & is now jailed himself

For the 24 Ukrainian POWs who spent nine long months imprisoned in Moscow, the moral and material support they received from Konstantin Kotov and other Russian activists was of enormous importance. On their release, the men learned that Kotov himself has now been imprisoned under Russia’s most repressive anti-demonstration law and their response was immediate. Within just three days they had collected 12,400 UAH, which Nikolai Polozov, the lawyer who coordinated their defence team, will take to Moscow for them and ensure that it is used to help Kotov as he once helped them. All but two of the former POWs are Ukrainian naval seamen, whose motto, Polozov notes, is “We don’t abandon our own people”, adding, quite rightly, that this applies fully to Kostya Kotov who helped to bring them parcels every second week, attended their court hearings. “The thought that they were not forgotten, that there were people outside who were concerned about them, made it possible for the seamen to worthily and firmly endure the hardship and deprivation”.

It was not only the seamen who had reason to be grateful for Kotov’s acts of solidarity and active assistance. Lutfiye Zudiyeva, one of the coordinators of Crimean Solidarity, recalls how Kotov came to support the huge number of Crimean Tatar activists detained for peaceful solidarity with four political prisoners on 10 and 11 July this year. He even ran to the police building where the detained men were being forced into a police van and gave them biscuits, fruit juice and sweets. Zudiyeva notes that he waited until late in the evening because “he couldn’t do otherwise”. Kotov was invariably present at all demonstrations in Moscow demanding the release of Ukrainian political prisoners.

Kotov’s unwavering solidarity with Russia’s Ukrainian victims of persecution may well have contributed to his arrest on 12 August and subsequent four-year sentence, passed, Polozov says, with the speed of the notorious ‘troiki’ that passed death sentences during Stalin’s Terror. It is surely no coincidence that the only two men so far imprisoned under a draconian law passed in 2014 both actively spoke out in defence of Ukraine and the Kremlin’s Ukrainian hostages.

Ildar Dadin was the first Russian to receive a prison sentence on 7 December 2015 under a new Article 212.1 of the Russian Criminal Code, introduced in July 2014. That envisages a sentence of up to 5 years if a court has issued three rulings on administrative offences within 180 days. With detentions and administrative prosecutions on fictitious charges of ‘infringing the rules for holding a public event’ standard, it is very easy to accumulate such prosecutions, even for holding supposedly legal single-person pickets.

His case gained international publicity, especially after he was subjected to torture and then faced reprisals for having talked about his treatment. The Kremlin clearly decided it was better to have him released and in February 2017, Russia’s Supreme Court revoked the sentence. Almost simultaneously, the Constitutional Court recommended amendments to the norm and stated that criminal liability for infringements at public events should be commensurate with the danger to the public of the actions. Criminal liability should not be applied in cases where the infringements were merely formal and caused no harm. The court was also told that the person’s intent to infringe established procedure for organizing or holding a public event needed to be proven.

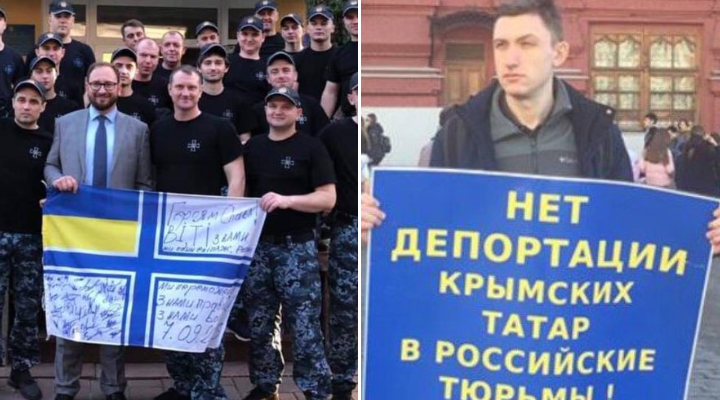

Konstantin Kotov with a placard in defence of Crimean Tatar political prisoners. It reads: No deportation of Crimean Tatars to Russian prisons!

Konstantin Kotov with a placard in defence of Crimean Tatar political prisoners. It reads: No deportation of Crimean Tatars to Russian prisons!

For some time after Dadin’s release, the article was not applied. However the regime has recently begun cracking down very hard on peaceful protesters, and three people have already been charged under 212.1 this year. It is, however, noticeable that Kotov is the first person to date to have been imprisoned immediately, even before the ‘court’ had passed a verdict. Details about the specific administrative prosecutions can be found here. None of them comply with the Constitutional Court’s guidelines for which 212.1 can be used, yet on 5 September 2019, less than three weeks after his arrest, Kotov was sentenced by ‘judge’ Stanislav Minin from the Tverskoy District Court to four years’ imprisonment. He has been recognized as a political prisoner by the Memorial Human Rights Centre and Amnesty International has called the verdict in Kotov’s ‘trial’ a verdict on human rights in Russia.

The 24 Ukrainian seamen had been seized when Russia attacked three Ukrainian naval boats in the Kerch Strait on 25 November 2018. After initiatives launched by Crimean Tatars elicited a huge amount of money, clothes, food products, etc., often from ordinary Crimeans, not known for any civic activism, Russia moved the men to Moscow where it brought preposterous charges of illegally crossing ‘Russia’s border’ against all of them.

The men were well-represented, and all held out wonderfully, refusing to ‘cooperate with the investigators’ and simply reiterating that they were prisoners of war and citing the Third Geneva Convention. Russia had been ordered by the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea to release the men back on 25 May 2019, but was ignoring this, until 7 September, when all 24 men, together with 11 political prisoners were returned to Ukraine. It was a 35 to 35 prisoner exchange, but there seem grounds for believing that the Kremlin’s sudden willingness to release political prisoners, like Oleg Sentsov, whom it had held for over five years, as well as the POWs, was likely linked with Ukraine’s capture of Volodymyr Tsemakh, a Donbas militant commander who is at least a witness, possibly a suspect in the criminal investigation over the downing by a Russian BUK missile of MH17 and the swift removal of the BUK missile launcher back to Russia.