• Research / Analysis of the human rights situation in Ukraine / Human rights in Ukraine – 2006. Human rights organizations’ report

Human rights in Ukraine – 2006. V. The Right to privacy

The right to privacy is largely guaranteed by the Constitution of Ukraine. Article 30, for example, guarantees territorial privacy (inviolability of dwelling place), while Article 31 concentrates on privacy of communications (privacy of mail, telephone conversations, telegraph and other correspondence) and Article 32 – on privacy of information. (“No one shall be subject to interference in his or her personal and family life, except in cases envisaged by the Constitution of Ukraine. The collection, storage, use and dissemination of confidential information about a person without his or her consent shall not be permitted …”). In addition, Article 28 guarantees certain aspects of physical privacy (“No person shall be subjected to medical, scientific or other experiments without his or her free consent.”)

Constitutional norms providing an exhaustive list of grounds for intrusion into privacy and the conditions which must be met have not been sufficiently developed in laws and subordinate legislation. The rather unclear formulation, or indeed lack of regularization of permissible grounds for restricting the right to privacy, the scope and methods used remain the least resolved issues in legislative regulation of privacy with this leading in practice to countless violations.

Liability for infringements of the right to privacy is set down in criminal, civil and administrative legislation, yet the lack of clarity in this area makes such norms practically impossible to apply.

The situation is generally deteriorating especially as regards confidentiality of communications and information.

1. Communications privacy

Current legislation does not stipulate either any clear grounds for interception of information from communication channels (phone tapping, mobile tapping, Internet tapping or e-mail tracking), or the specific period when such information is intercepted, or the circumstances in which the information should be destroyed and how it can be used. There are clearly not enough guarantees of the lawfulness of interception of information from communication channels. Consequently, no one can control the number of permits and the necessity for listening-in, and the individuals, in relation to whom such measures have been applied, are not aware of this fact and can, therefore, neither challenge such actions in court nor otherwise defend their right to privacy.[2]

In March 2006 representatives of the electoral bloc “Nasha Ukraina” [“Our Ukraine”] Roman Zvarych, Roman Bessmertny and Petro Poroshenko, as well as the Minister of Internal Affairs Yury Lutsenko publicly stated that the former Head of the Security Service [SBU] Oleksandr Turchynov had used his official position to monitor telephone conversations involving public officials from different State authorities. According to Roman Bessmertny, transcripts of his telephone conversations had been circulated. In addition, international calls had been tapped. Oleksandr Turchynov denied having authorized any wiretapping of politicians and public officials from the highest State bodies. However the SBU publicly confirmed that there had been unlawful wiretapping, and the Prosecutor General launched a criminal investigation into this.

While reporting on the work of the Security Service during the first 9 months of 2006, the Head of the SBU stated that 10 cases of unlawful wiretapping had been uncovered, these having been carried out by State bodies or commercial outfits[3]

On 19 December, following a special operation in Kyiv, the SBU put a stop to the illegal activities of a commercial firm which had been carrying out unlawful wiretapping of members of the public and, it cannot be excluded, certain high-ranking public officials. A special device for tracking, tapping and recording conversations via the GSM cellular network was confiscated from an employee of the firm. According to specialists, the device was the most complex of its kind with a market value of nearly 420 thousand US dollars depending on its features. Security Service officers are looking into how it was brought here and where from.[4]

On 5 February 2007 the Deputy Prosecutor General V. Pshonka initiated a criminal investigation into a breach of privacy over a telephone conversation between Speaker of the Verkhovna Rada O. Moroz and the United Kingdom Ambassador, a run down of which had been published in January 2007 on the Internet. The Kyiv prosecutor has been made responsible for the pre-trial investigation into this criminal matter. The SBU was accused of the wiretapping which it was claimed had been commissioned by Ukraine’s President. The SBU categorically denied such charges, referring to information from an internal examination.[5]

It should be noted that in NOT ONE of these cases were those responsible punished, or at least the public have not been informed of any such cases. This demonstrates inadequate protection of privacy.

The press reported only one such case, although in fact it is difficult to gauge the scale of this. In May the Holosiyivsky District Court in Kyiv convicted a person from Kyiv detained by SBU officers for illegally making, installing and using a technical device for tacit unlawful wiretapping. The actual device had been removed by offices of the SBU Counter-espionage Department in October 2005. It was later established that the micro-transmitter installed in the firm had been ordered by business competitors. The Holosiyivsky District Court fined Oleksandr H. under Article 182 of the Criminal Code.[6]

On 11 September 2006 it was learned that the Prosecutor General had carried out a check of both the SBU and the Foreign Intelligence Service [SZRU, from the Ukrainian] for possible unsanctioned wiretapping of National Deputies and high-ranking officials. The check was carried out at the request of National Deputy Volodymyr Sivkovych who had stated that he was able to produce more than 100 hours of telephone conversations taped by the Security Services. The SBU categorically denied any involvement in intercepting politicians’ phone calls. The check did not find any evidence of the two Services having carried out such wiretapping[7]

Exact figures for the extent of wiretapping carried out in Ukraine are not available as official statistics are not provided by the authorities. However it did become known that in 2002 the courts had issued over 40,000 warrants for wiretapping. It was also officially confirmed that in 2003 the Appeal Court of the smallest region in Ukraine, the Chernivtsi region, had issued 823 warrants for the interception of information from communications channels.[8]. According to information from the Prosecutor General’s Office, the number of such warrants by September 2005 was in excess of 11 thousand, with the results of the wiretapping having been used in only 40 cases.[9] Following wide publicity over these facts, the SBU included such information in the “List of Items of information which constitute State secrets” [LIISS][10]. The Security Service thus, instead of protecting people’s rights, simply classified as secret information about infringements of their rights. .

In an interview given on 7 November 2006, the Head of the SBU stated: “At present the number of technical operations has approximately halved since last year, while the effectiveness of using the material as evidence in court has remained the same, or has even increased. We are thus paying attention to the quality, not the amount of such work. And I think that that is significant progress”.”[11] It follows from this that around 20 thousand interception warrants are issued per year which is 10 times more than in other democratic countries, where this information is made public in annual reports, and not classified as a 5State secret.

On 7 November 2005 President Yushchenko passed Decree №1556/2005 “On observance of human rights in carrying out investigative operational and technical measures”, however he continues to rely on institutional changes in the law enforcement agencies, and not on the establishment of procedural guarantees against abuses. Such measures appear superficial. The transfer of wire tapping of citizens to one body, in this case the SBU will not resolve the problem. In our opinion, none of the measures outlined in the Decree will improve the situation since they fail to take into account both the positive experience gained by other countries, and the standards set by the European Court of Human Rights.

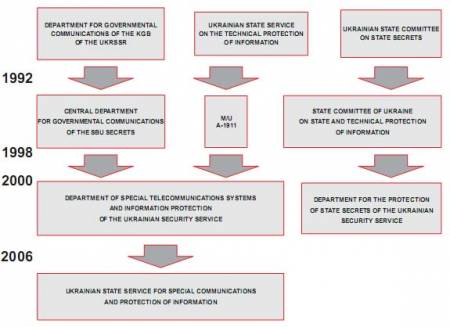

The President’s Decree speaks of the need to create a single State body entitled to intercept information from communication channels, this being a State Service for Special Communications and Protection of Information as a central authority with special status. Its key functions would be to implement State policy on protecting State-owned information resources in networks for transmitting data, to safeguard the functioning of the State system of governmental communications, a National system for confidential communications, cryptographic and technical protection of information.

One positive aspect can be noted in the fact that this Service is to be formally fully separate from the SBU, although it is effectively made up of its former employees.

History of the creation of the State Service for Special Communications

The first task after the creation of such a single State body was to transfer under its control all equipment for intercepting communications held by law enforcement agencies. Here an interesting situation emerged. It transpired that the latter were unable to account for the number of packs for intercepting communications they had. The SBU asked several times for all equipment to be handed over to the newly-created Service which now has the exclusive right to intercept communications in Ukraine.

„..When we began trying to establish what special packs they had for wiretapping, including mobiles, and for finding out where the owner of the mobile was at any point in time, it turned out that the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) had only used money from Budgetary allocations to buy 9 such packs, and yet 17 were handed over to the Ukrainian Security Service. That suggests that some other sources of financing may have been used to buy special technology. The possibility follows also that there was unsanctioned purchase and use of such devices, including with the aim of serving he interests of particular political forces or commercial structures. We are carrying out an internal investigation into this. According to operational information, 8 of these systems simply vanished prior to the change in management of the MIA. Where are they now? Which of us, esteemed citizens, is having our conversations tapped? Who is under surveillance? Unfortunately I didn’t inherit this information”, the Minister of the MIA told parliament at the beginning of 2007.[12]

On 26 November 2006 Parliament passed in its first reading the Draft Law “On amendments to some legislative acts of Ukraine on preventing interception of information from telecommunication channels”[13]. In March 2007 the draft law was ready for its second reading. Despite certain positive aspects, the given draft does not change the situation to any significant extent, since it does not establish any of the additional safeguards against abuse, recognized by international law, for example, the judgments of the European Court of Human Rights. The draft only broadens the limits of criminal liability for infringing confidentiality of correspondence.

In order to counter so-called “computer terrorism”, the SBU is carrying out measures aimed at monitoring the use of the Internet and regulating the Ukrainian segment of the network. Despite the lack of legally established powers of the SBU in this sphere, the latter is continuing to introduce technical possibilities for monitoring the use of the Internet.

In accordance with Order No. 122 of the State Committee on Communications from 17 June 2002, only Internet providers which have installed a state system of monitoring (analogous to the Russia SORM – “System of ensuring investigative activity”) and have received the appropriate certificate from the SBU may provide access to global information networks to institutions and organizations which receive, process, circulate and store information which is the property of the state. Internet providers were particularly critical of the demand of the SBU that such equipment be installed at the providers’ expense. It is impossible to separate the traffic of state and non-state users of their services and protect the latter from monitoring. In this way all clients of companies which agreed to install the equipment would automatically be exposed to permanent monitoring by the SBU.

The change of leadership in Ukraine did not bring any change in this area. The SBU in 2005 sent letters to state institutions instructing them to connect to “correct” providers.[14] The open joint stock company “Ukrtelekom”; the joint enterprise “Infocom”; the Limited Liability Company (LLC) “Global Ukraine”; LLC "Elvisti"; LLC "UkrSat"; LLC "Luckynet"; LLC "Citynet"; LLCC "Maket"; LLC “Golden Telecom”; LLC “Adamant” and LLC “Optima special communications”. The last three were joined to the list in 2006.

According to specialists, the SBU already illegally intercepts messages and carries out constant surveillance over approximately 50 % of the Ukrainian traffic. The level of surveillance, moreover, at the regional level can rise to 90% since regional providers find it harder to stand up to the SBU.

The Ministry of Justice of Ukraine, in response to a letter from the Internet Association of Ukraine regarding the legality of Order No. 122 of the State Committee on Communications stated that it was legal, however later, on 23 November 2005, this time answering the same question posed by the UHHRU, it declared it unlawful.[15]

“At the same time, with regard to the issue of the Order of the State Committee for Communications No. 122 of 17.06.2002, we would state that the Ministry of Justice in a letter dated 13 October 2005 No. 37229-24 called upon the Ministry of Transport and Communications within a five-day period to declare no longer in force the Order No.122 of the State Committee for Communications and Computerization of Ukraine from 17.06.2002”. .

And indeed, in accordance with Conclusion of the Ministry of Justice from 4 August 2006 No. 13/71, Order No. 122 was removed from the State Register of normative legal acts on 21 August 2006. The given normative act has thus become null and void. Yet regardless of this, all the activities carried out on the basis of that Order continue to this day. No equipment has been dismantled, and the list of providers is in fact still functioning.

UHHRU approached the Security Service of Ukraine asking on what grounds the Internet was continuing to be monitored when Order No. 122 had been revoked. The SBU’s reply stated that such activities were on the basis of the Law on investigative operations. However, given the functioning of a monitoring system, doubts arise as to whether constant monitoring is really carried out solely within the boundaries of investigative operations launched. The point is that the specific nature of the monitoring demands constant surveillance of traffic, and not selective surveillance, largely of a specific person.

2. The Case of Volokhy v. Ukraine[16]

In this case, the applicants Olga and Mykhaylo Volokh who live in Poltava complained about the interception and seizure of their postal and telegraphic correspondence and the violation of their right to of their right to respect for their correspondence as provided in Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

The Circumstances of the case

In May 1996 the Poltava Regional Police Department (hereinafter – the PRPD) instituted criminal proceedings for tax evasion against Mr V., who is, respectively, the son of the first applicant and the brother of the second applicant. On 28 May 1996 the investigator placed Mr V. under an obligation not to abscond.

On 4 September 1996, following the failure of Mr V. to appear for interrogation and in the absence of information about his whereabouts, an arrest warrant for Mr V. was issued.

On 6 August 1997 the PRPD investigator issued an order for interception and seizure of the postal and telegraphic correspondence of the applicants (hereinafter – “the interception order”) on the following grounds:

“The private entrepreneur Mr V., during the period between 1 January 1994 and 1 January 1996, intentionally did not pay taxes to the State budget in the amount of UAH 12,889[17], having caused damage and substantial losses to the State. On 28 May 1996 the preventive measure – obligation not to abscond – was ordered in respect of Mr V., but, having been summoned by the investigator, Mr V. did not come to him, and his whereabouts at the present are unknown. On 4 September 1996 the preventive measure – detention – was ordered in respect of Mr V. ... Mr V. may inform his mother and brother about his whereabouts, using the postal and telegraphic correspondence.”

On 11 August 1997 the President of the Zhovtnevyy District Court approved the interception order by having signed it. The applicants maintained that they had learned about this order by chance at the end of 1998.

On 4 May 1998 the criminal case against Mr V. was terminated as being time-barred.

According to the applicants, Mr V. had appeared in summer 1998 and met with the investigator in his case. During this meeting he found out about the interception order. On 28 May 1999 the PRPD investigator cancelled the interception order on the grounds that the criminal case against Mr V. had been closed and there were no further need to intercept the applicants’ correspondence. This cancellation was approved and signed by the President of the Zhovtnevyy District Court the same day.

By letter of 19 July 1999, the Poltava Regional Prosecutor’s Office, in reply to their complaint, informed the applicants that the interception of their correspondence had been ordered lawfully and therefore the law-enforcement officers incurred no liability…. By letter of 6 January 2000 to Mr V., in reply to his complaints about the criminal proceedings against him, the General Prosecutor’s Office noted, inter alia, that the interception order was not well-founded. By letter of 1 February 2000, the first applicant was informed that on 15 August 1997 (15 September 1997 according to the Government) a letter addressed to her had been intercepted by the police but, as it contained no information about the whereabouts of Mr V., it was not seized but was forwarded to her.

17. On 20 January 2000 the applicants claimed compensation from the Head of the PRPD for the damage caused by ordering the interception of their correspondence. By letter of 27 January 2000, the Head of the PRPD informed the second applicant that the interception order had been lawful and that, therefore, there were no grounds to award damages.

21. On 18 February 2000 the applicants lodged a claim with the Leninsky District Court of Poltava against the PDPR seeking compensation for the moral damage caused by the interference with their correspondence. In support of their claim, they referred to the letter of the GPO of 6 January 2000, where it was acknowledged that the interception order lacked grounds.

On 11 October 2001 the Leninsky District Court found against the applicants. The court concluded that the interception order had been lawful and well-founded, the criminal proceedings against Mr V. having been terminated on non-exonerative grounds (нереабілітуючі обставини), and that the applicants did not prove that they had suffered any moral damage due to the interference with their correspondence. The court held that the applicants’ claim was unsubstantiated and that the General Prosecutor’s Office’s letter of 6 January 2000 could not be a ground for awarding them any damages. It, therefore, rejected the applicants’ claim in full.

On 8 January 2002 the Appellate Court of Poltava Region upheld the decision of the first instance court. On 9 February 2004 the panel of three judges of the Supreme Court rejected the applicants’ request for leave to appeal in cassation.

19. By letter of 19 November 2000, the Head of the PRPD informed the second applicant that the seizure of correspondence had been in compliance with the law and that the applicant had no right to compensation, given that the criminal case against his brother had been terminated on non-exonerative grounds. By letter of 21 November 2000, the Poltava Regional Prosecutor’s Office informed the second applicant that the issue of compensation was within the competence of the courts

II. Alleged violation of Article 8 of the Convention

A. Whether there has been an interference

42. It was not disputed by the parties that the decision on interception of the applicants’ correspondence constituted “an interference by a public authority” within the meaning of Article 8 § 2 of the Convention with the applicants’ right to respect for their correspondence guaranteed by paragraph 1 of Article 8.

B. Whether the interference was justified

The cardinal issue that arises is whether the above interference is justifiable under paragraph 2 of Article 8. … The Court reiterates that powers of secret surveillance of citizens in the course of criminal investigations are tolerable under the Convention only in so far as strictly necessary.[18]

If it is not to contravene Article 8, such interference must have been “in accordance with the law”, pursue a legitimate aim under paragraph 2 and, furthermore, be necessary in a democratic society in order to achieve that aim.

The Government maintained that the decision on interception of the applicants’ correspondence had been given in accordance with Article 187 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. The applicants did not contest this argument, but maintained that the provisions of Article 31 of the Constitution had not been respected.

The Court notes that Article 31 of the Constitution, Article 187 of the Code of Criminal Procedure and Article 8 of the Law “on search and seizure activities”[19] provided for the possibility to conduct interception of the correspondence in the framework of criminal proceedings and the search and seizure activities (see paragraphs 25-27 above).

There was, therefore, a legal basis for the interference in domestic law.

49. As regards the requirement of foreseeability, the Court reiterates that a rule is “foreseeable” if it is formulated with sufficient precision to enable any individual – if need be with appropriate advice – to regulate his conduct. The Court has stressed the importance of this concept with regard to secret surveillance in the following terms [20]

“The Court would reiterate its opinion that the phrase ‘in accordance with the law’ does not merely refer back to domestic law but also relates to the quality of the ‘law’, requiring it to be compatible with the rule of law, which is expressly mentioned in the preamble to the Convention ... The phrase thus implies – and this follows from the object and purpose of Article 8 – that there must be a measure of legal protection in domestic law against arbitrary interferences by public authorities with the rights safeguarded by paragraph 1 ... Especially where a power of the executive is exercised in secret, the risks of arbitrariness are evident ...

Since the implementation in practice of measures of secret surveillance of communications is not open to scrutiny by the individuals concerned or the public at large, it would be contrary to the rule of law for the legal discretion granted to the executive to be expressed in terms of an unfettered power. Consequently, the law must indicate the scope of any such discretion conferred on the competent authorities and the manner of its exercise with sufficient clarity, having regard to the legitimate aim of the measure in question, to give the individual adequate protection against arbitrary interference.”

51. The Court notes in this connection that the requirements of proportionality of the interference, and of its exceptional and temporary nature were stipulated in Article 31 of the Constitution and Article 9 of the Law of Ukraine “on Search and Seizure Activities” of 18 February 1992 (see paragraphs 25 and 27 above). However, neither Article 187 of the Code of Criminal Procedure in its wording at the time of the events, nor any other provision of Ukrainian law contained a mechanism which would ensure that the above principles were respected in practice. The provision in question (see paragraph 26 above) contains no indication as to the persons concerned by such measures, the circumstances in which they may be ordered, the time-limits to be fixed and respected. It cannot therefore be considered to be sufficiently clear and detailed to afford appropriate protection against undue interference by the authorities with the applicants’ right to respect for their private life and correspondence

Furthermore, the Court must be satisfied that there exist adequate and effective safeguards against abuse, since a system of secret surveillance designed to protect national security and public order entails the risk of undermining or even destroying democracy on the ground of defending i.[21]). Such safeguards must be equally established by law in unequivocal manner and be applied to the supervision of the relevant services’ activities. Supervision procedures must follow the values of a democratic society as faithfully as possible, in particular the rule of law, which is expressly referred to in the Preamble to the Convention. The rule of law implies, inter alia, that interference by the executive authorities with an individual’s rights should be subject to effective supervision, which should normally be carried out by the judiciary, at least in the last resort, since judicial control affords the best guarantees of independence, impartiality and a proper procedure[22]

In the instant case, the Court observes that the review of the decision on interception of correspondence under Article 187 of the Code of Criminal Procedure was foreseen at the initial stage, when the interception of correspondence was first ordered. The relevant legislation did not provide, however, for any interim review of the interception order in reasonable intervals or for any time-limits for the interference. Neither did it require or authorise more involvement of the courts in supervising interception procedures conducted by the law-enforcement authorities. As a result, the interception order in the applicants’ case remained valid for more than one year after the criminal proceedings against their relative Mr V. had been terminated and the domestic courts did not react to this fact in any way.

The Court concludes that the interference cannot therefore be considered to have been “in accordance with the law” (see paragraph 49 above) since Ukrainian law does not indicate with sufficient clarity the scope and conditions of exercise of the authorities’ discretionary power in the area under consideration and does not provide sufficient safeguards against abuse of this surveillance system.

It follows that there has been a violation of Article 8 of the Convention arising from the interception of the applicants’ correspondence.

Alleged violation of Article 13 of the Convention

55. The applicants complained about a lack of domestic remedies to seek redress for the unlawful interference with their correspondence. They relied on Article 13 of the Convention.

58. The Court recalls its reasoning in the Klass case (cited above, §§ 68-70), in which it observed that it was the secrecy of the measures which rendered it difficult, if not impossible, for the person concerned to seek any remedy of his own accord, particularly while surveillance was in progress. Nevertheless, in the Klass case it was established that the competent authority was bound to inform the person concerned as soon as the surveillance measures were discontinued and notification could be made without jeopardising the purpose of the restriction, and such person had a number of remedies available to him or her. Moreover, in the Klass case the Court took into account the existence of a system of proper control over surveillance measures and found no violation of Article 13.

59. From the Government’s submissions, it does not appear that the Ukrainian legal system offered sufficient safeguards to persons under surveillance, because there was no obligation to inform a person that he or she was under surveillance. Even when the persons concerned learned about the interference with their correspondence, like in the present case, the right to question the lawfulness of the decision on interception as guaranteed by the domestic law (see paragraphs 25 and 27 above) appears to be limited in practice, since the only implementing mechanism is provided by the Law of Ukraine “on the procedure for the compensation of damage caused to the citizen by the unlawful actions of bodies of inquiry, pre-trial investigation, prosecutors and courts”. In the Court’s opinion, this Law, which is worded in very general terms at least in so far as persons other than the accused are concerned, could have a remedial effect in situations comparable to the one of the applicants, touched by surveillance measures in the context of criminal proceedings against a third person. However, its application and interpretation by the domestic courts, as in the present case, does not appear to be sufficiently broad to encompass complaints of persons other than the accused.

The foregoing considerations are sufficient to enable the Court to conclude that the applicants did not have an effective domestic remedy, as required by Article 13, in relation to their complaints under Article 8 of the Convention about the surveillance measures involving their postal and telegraphic correspondence.

61. The Court therefore dismisses the Government’s preliminary objection and holds that there has been a breach of Article 13 of the Convention.

3. Information privacy and personal data protection

On 22 December 2005 parliament passed the Law “On access to court rulings”. From 1 June 2006 an information system has been accessible via the Internet containing rulings handed down by Ukrainian courts. Previously only parties to a specific case had access to the rulings. In order to protect the right to privacy of parties in court proceedings, the Law allows for personal information to be removed.

Ukraine has not become a signatory to the Council of Europe’s Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data, No. 108. However in 2005, a Ministry of Justice working group which includes nongovernmental organizations involved in defending the right to privacy began work in this field.

The Action Plan Ukraine – EU for 2005 stipulates the ratification of Convention No. 108 and the Additional Protocol to it, with the necessary amendments introduced at the same time to domestic legislation. This has yet to be implemented.

During 2005 and 2006 this working group drafted a Law “On Personal Data Protection” which incorporates the provisions of the above-mentioned Council of Europe Convention, the Directive 95/46/ЄС of the European Parliament and the Council of 24 October 1995 on the Protection of Individuals with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, the Directive 97/66/ec of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 December 1997 concerning the processing of personal data and the protection of privacy in the telecommunications sector, as well as the Recommendations of the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers concerning personal data. The Draft Law has still not been tabled in parliament.

During 2006 parliament continued its consideration of another draft law “On Personal Data Protection”[23]. This had been passed in its first reading back in 2003. In March 2006 it was passed in full. However it totally failed to take on board European standards of personal data protection, sometimes confusing these with technical protection of databases. The draft presented no serious safeguards of privacy in automated systems. A number of organizations approached the President asking him to use his power of veto, which he did. On 3 November an attempt was made to charge it through without taking the President’s suggestion into consideration, however the attempt failed and the draft was sent back for reworking. At that time Ministry of Justice personnel became involved in the process. They effectively used the variant drafted by the working group and took into account most European standards of personal data protection. On 9 January 2007 the draft law was passed in a significantly reworked and improved version and having taken into consideration the President’s suggestions. However, without any particular grounds, the President once again vetoed the draft. Then in February it was again not passed by parliament and sent back for further refinement.

Meanwhile, without a normative base for personal data protection, discussion of draft laws has been continuing in parallel to the actual creation of a Single State Automated Register of Individuals< as well as other state registers containing personal data, including a register of voters.

Parliament has in past years repeatedly rejected draft laws on creating such a Register.

In response to this and despite the lack of any legal grounds, on 30 April 2004 the then President issued Decree No. 500 «On the Creation of a Single State Register of Individuals» which sanctioned the creation and running of a Single Register The Decree empowered the Ministry of Internal Affairs to create and maintain this single register on the basis of a Single State Automated Passport System (hereafter – SSAPS), based on a concept approved by a Cabinet of Ministers Resolution back in 1997.

In order to carry out the work on creating SSAPS, the Ministry of Internal Affairs appointed the private company “Corporation “SSAPS”. This meant that personal data which Ukrainian citizens passed to a government agency were then passed on to a private structure. Later the MIA management also empowered this private structure with the issue of passport forms, the State Automobile Inspection [traffic police] database, and so forth.

President Yushchenko with his Decree No.457 from 10 March 2005 revoked President Kuchma’s Decree from 30 April 2004 «On the Creation of a Single State Register of Individuals», together with the plan for introducing a new style of passport in the form of a plastic card on the basis of SSAPS .[24]

Nonetheless on 15 December 2006 parliament passed in its first reading a draft law “On a National Demographic Register”.[25] This draft is a reworded version of the old draft laws on a Single State Automated Register of Individuals.

The main point of this and previous draft laws is to create a single automated database about members of the public whereby all information about any Ukrainian citizen gathered by any government body or State institution will be held under one number. Such a system will inevitably lead to violations of privacy. Precisely for that reason, the Hungarian Constitutional Court back in 1991 declared an analogous system unconstitutional. There is no such system in any developed democratic country. Yet parliament has begun creating it. Effectively, as can be seen from the above, the system is being created in practice, without any proper legal grounding.

At the beginning of 2007 parliament passed a law on a State Register of Voters. The draft law had been in parliament since February 2004. It should be noted that this draft law is particularly strong on observing the right to privacy although it does not contain procedure for independent control over the use of the register.

President Yushchenko instructed the Head of Ukraine’s Council of National Security and Defence (CNSD), Anatoly Kinakh to prepare a session of the CNSD on improving work connected with the preparation, registration and issue of passport documents and bringing them into line with international standards for systems of individual registration. On 23 February 2006, on the basis of an Instruction from the Secretary of the CNSD, the appropriate working group was created. Such a development shows that the issues of a passport system and personal registration are considered to have implications for national security.

However, despite the lack of legislative regulation and the cancellation of the relevant Presidential Decrees, the MIA is still continuing to create the Single State Automated Passport System, with financing from the State Budget being allocated for this, and passports for international travel are still issued according to the previously established format.

In October 2005 the MIA submitted a package of documents to the Cabinet of Ministers in order to “produce a Ukrainian citizen’s card, this being a plastic card with an inserted electronic chip which will be extremely secure. The chip will contain the card number which will be the same for the Tax Service, and for the Pension Fund. The chip will contain all necessary information about the person, and in addition it will be possible to add information about whether the person has a driving licence.”

In 2005 and 2006 implementation of this initiative had not formally begun although in practice the MIA have long been carrying it out without any legal basis.

In response to this initiative, the UHHRU sent a letter to the Prime Minister and also began a campaign collecting signatures for an open letter to those in power, which more than 100 people endorsed.[26]. The human rights activists were demanding what would seem at first glance to be simple things, which those in authority could simply not understand:

1) With regard to plastic cards

- that a Law on Personal Data Protection be passed;

- that such cards be prepared only by a STATE structure;

- that a person should be given the opportunity to learn what data was contained in;the card chip and to have it changed.

2) With regard to the individual identification code:

- that different codes should be used separately, and that a SINGLE code for accumulating all information about a person should not be created;

- that codes should be used ONLY for the purpose for which they were designed;

- that their use should be determined by a Law on Personal Data Protection.

At the present time the main electronic classifier on the basis of which personal data is gathered and processed is the identification code which is issued by the State Tax Administration. The sphere of its use is constantly being expanded and far exceeds the aim for which it was introduced, that is, tax registration. Without an identification code one cannot legally find work, have access to pensions, exercise ones right to education, receive a student grant or unemployment benefit, organize concessions, open bank accounts, register business activities, etc.

Therefore in reality we have a situation where the administrative practice of State executive bodies is knowingly violating the Law of Ukraine on a Single Register of Individual taxpayers, and is using the tax number for purposes not envisaged in by this Law.

Another serious problem is that the authorities and State institutions regularly divulge confidential information about individuals. It is a standard occurrence for information to be disclosed about a person’s state of health, their income and so forth.

You can obtain computer data containing confidential information anywhere. This can be seen from the following advertisement.

We draw your attention to the latest databases

Telephone: 8-066-295-91-36

1. State Customs Committee of Ukraine 2003/2004/2005/2006 Database on foreign economic activity (customs) * 250 UAH

Sender, address of: sender, recipient, recipient’s address, bank code, MFO [bank no.], address of the bank, account no., person responsible for financial regulation, his/her address; type of goods, weight, value, direction (import-export)

2 Ukraine – Ministry of Statistics – 2006.01.01 * 250 UAH

Organizations, addresses, telephones, institutions, staff, infringements, cases of liquidation

3. Physical persons * 250 UAH

Surname, first name, patronymic, date code was received, date of birth, place of birth, place of residence, telephone, sex

4. Income of physical persons in Ukraine 2004/2005 * 400 UAH

Income and taxes, place of work, information about employer

5. State Tax Administration 2005 * 250 UAH

Tax [Administration] of Ukraine 20045 + State Committee of Statistics of Ukraine

Database on Ukrainian registered businesses. All information on each business, including: name, legal and actual address, registration number, date of registration, registering body, size of statutory funds, information about the founders, etc 981,000 businesses. 1.5 Gb as of 20 December

6 State Register of Businesses * 250 UAH

Registration data about businesses, their founders, account numbers of the businesses, addresses, branches, foreign representative officers.

And also all databases on Russia

Yet the State Tax Administration [STA] which administers the majority of these databases maintains that they have no recorded leaks of information. On the other hand there is simply no other way of obtaining this information except through copying the database at the STA.

The investigation by law enforcement agencies into this case is continuing.

According to figures from SBU, over 2006 28 attempts to sell databases of State institutions and organizations containing confidential information held by the State were thwarted.[27] No more detail is available about these cases, for example, whether the individuals were convicted and what databases exactly were they trying to sell.

The All-Ukrainian Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS reports of many cases where medical diagnoses of people were HIV have been disclosed. In a lot of regions people with AIDS are issued with special documents which render the confidentiality of such diagnoses meaningless.

On 25 July 2006 the Pechersky District Court in Kyiv concluded its examination of the administrative claim lodged by Svitlana Yurivna Poberezhets, an anaesthetist and resuscitation expert from the Vinnytsa City Clinical Hospital against the Ukrainian Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Employment and Social Policy of Ukraine, the Social Insurance Fund for Temporary disability and the Industrial accident and occupational diseases which have caused disability Fund and the Ministry of Justice of Ukraine. She was demanding that the court recognize as unlawful the normative legal act in the form of a Joint Order of the administrative respondents “On approving the form and technical description of a medical certificate and instructions on the procedure for filling in the form on temporary inability to work”. In her administrative claim, Svitllana Poberezhets argued that the requirement to provide information about a person’s diagnosis and the code of their illness according to the International Classification of Diseases should be declared unlawful as it violated the constitutional right of Ukrainian citizens to privacy ((confidentiality of medical records).

The ruling was not appealed and has come into force. From now on Ukrainian doctors may not indicate the diagnoses of their patients on medical certificates, this meaning that those at work will not be able to find about what the employee’s illness was. In 2005 almost 11 million such medical certificates were issued in Ukraine.[28]

The Vinnytsa Human Rights Group (VHRG) considers the ruling of the Pechersky District Court in the case involving medical certificates to be an important precedent and a breakthrough in protecting personal information in Ukraine. At the same time, the VHRG notes that there are a whole range of other normative legal acts issued by the Ministry of Health which enable the disclosure of private information about a person’s state of health (for example, information about a person’s diagnosis is provided according to where they are studying by adding it to the section “Diagnosis” in the certificate for being released from lessons or lectures). Information about children’s health condition is virtually on open access in schools and there have been cases where such information was disclosed.

| The Case of Panteleyenko v. Ukraine The European Court of Human Rights in the Case of Panteleyenko v. Ukraine [29] found that the right to privacy had been infringed over disclosure of information. In December 2001 20. In December 2001 Mr Panteleyenko instituted proceedings in the Novozavodsky Court against the Chernigiv Law College and its Principal for defamation. He alleged that, during the Attestation Commission’s hearing on 14 May 2001, the Principal had made three statements about him which were libellous and abusive, including one rudely questioning his mental health. The applicant demanded apologies and compensation for moral damage. During the trial, one of the applicant’s main arguments was that he had never suffered any mental health problems. He adduced to this effect a certificate supposedly issued by a psychiatric hospital, attesting that the applicant had never been treated there. The case of the defence was that the Principal had never uttered the obscenities attributed to him by the applicant. However, they challenged the authenticity of the above certificate and asked the court to verify the applicant’s assertions. On 21 March 2002 this application was granted and the Chernigiv Regional Psycho-Neurological Hospital was requested to provide information as to whether the applicant had undergone any psychiatric treatment. On 3 April 2002 the hospital submitted to the court a certificate to the effect that for several years the applicant had been registered as suffering from a certain mental illness and underwent in-patient treatment in different psychiatric establishments. However, several years earlier his psychiatric registration had been cancelled due to long-term remission (a temporary lessening of the severity) of the disease. This information was read out by a judge at one of the subsequent hearings; however, no reference to this evidence was made in the final judgment. On 3 June 2002 the Novozavodsky Court rejected the applicant’s claim as unsubstantiated. The court found, inter alia, that the applicant had failed to prove that the defendant had made any remarks about his sanity. The applicant appealed, challenging, inter alia, the lawfulness of the court’s request for information about his mental state. 25. On 1 October 2002 the Court of Appeal upheld the judgment in substance. On the same day the court issued a separate ruling to the effect that the first instance court’s request for information concerning the applicant’s mental health from the public hospital was contrary to Article 32 of the Constitution, Articles 23 and 31 of the Data Act 1992 and Article 6 of the Psychiatric Medical Assistance Act 2000. In particular, it was indicated that information about a person’s mental health was confidential, and its collection, retention, use and dissemination fell under a special regime. Moreover, the court held that the requested evidence had no relevance to the case. Summing up the above considerations, the Court of Appeal found that the judges of the lower courts lacked training in the field of confidential data protection and notified the Regional Centre for Judicial Studies about the need to remedy this lacuna in their training programme. 26. On 24 June 2003 the Supreme Court rejected the applicant’s request for leave to appeal under the cassation procedure. 57. In the instant case, the domestic court requested and obtained from a psychiatric hospital confidential information regarding the applicant’s mental state and relevant medical treatment. This information was subsequently disclosed by the judge to the parties and other persons present in the courtroom at a public hearing. 58. The Court finds that those details undeniably amounted to data relating to the applicant’s “private life” and that the impugned measure led to the widening of the range of persons acquainted with the details in issue. The measures taken by the court therefore constituted an interference with the applicant’s rights guaranteed under Article 8 of the Convention (Z v. Finland, judgment of 25 February 1997, Reports of Judgments and Decisions 1997‑I, § 71). 59. The principal issue is whether this interference was justified under Article 8 § 2, notably whether it was “in accordance with the law” and “necessary in a democratic society”, for one of the purposes enumerated in that paragraph. The Court recalls that the phrase “in accordance with the law” requires that the measure complained of must have some basis in domestic law (cf. Smirnova v. Russia, nos. 46133/99 and 48183/99, § 99, ECHR 2003‑IX (extracts)). It is to be noted that the Court of Appeal, having reviewed the case, came to the conclusion that the first instance judge’s treatment of the applicant’s personal information had not complied with the special regime concerning collection, retention, use and dissemination afforded to psychiatric data by Article 32 of the Constitution and Articles 23 and 31 of the Data Act 1992, which finding was not contested by the Government. Moreover, the Court notes that the details in issue being incapable of affecting the outcome of the litigation (i.e. the establishment of whether the alleged statement was made and the assessment whether it was libellous; compare and contrast, Z v. Finland, §§ 102 and 109), the Novozavodsky Court’s request for information was redundant, as the information was not “important for an inquiry, pre-trial investigation or trial”, and was thus unlawful for the purposes of Article 6 of the Psychiatric Medical Assistance Act 2000. 62. The Court finds for the reasons given above that there has been a breach of Article 8 of the Convention in this respect.. |

4. Territorial privacy

A major problem with respect to territorial privacy is seen in the shortcomings in legislation and even worse administrative practice over carrying out body searches or searches of a person’s home or workplace. Article 8 of the Convention also mentions respect for each person’s home.

For example, in the case mentioned above of Panteleyenko v. Ukraine, the Court also found that there had been a violation of Article 8 with respect to the search procedure. Criminal proceedings had been instituted against Mr Panteleyenko and a search was carried out of his office during which certain items were seized. In January 2000 the applicant instituted proceedings against the Prosecutor’s Office, seeking monetary compensation for the material and moral damage suffered as a result of the allegedly unlawful search of his office (i.e. loss of or damage to personal items and the seizure of documents essential for his professional activity)..

On 28 August 2000 the Novozavodsky District Court of Chernigiv granted this claim. The court declared the search of the applicant’s office “to have been conducted unlawfully”. In particular, it established that in breach of Article 183 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (hereafter “the CCP”) the investigator, being well aware of the applicant’s whereabouts (at that time he was undergoing hospital treatment), had failed to serve the search warrant on him. Moreover, contrary to Article 186 of the CCP, the authorities, instead of collecting the evidence relating to the criminal case, had seized all the official documents and certain personal items in the applicant’s office. This had effectively denied the applicant the possibility of performing his professional duties until 6 August 1999, when the relevant documents and items were returned to him. The court awarded the applicant UAH 14,140[30] in material and UAH 1,000[31] in moral damages.

On 16 January 2001 the Chernygiv Regional Court, on an appeal by the Prosecutor’s Office, quashed the decision of 28 August 2000 and remitted the case for fresh consideration. … .

(18). On 26 December 2001 the Novozavodsky Court examined the applicant’s claim and rejected it as being unsubstantiated. The court, referring to the Prosecutor’s Office’s ruling of 4 August 2001, found that the applicant’s case had been closed on non-exonerative grounds, within the meaning of Article 2 of the Law of Ukraine “On the procedure for compensation of damage caused to the citizen by unlawful actions of bodies of inquiry, pre-trial investigation, prosecutors and courts” 1994, and therefore the applicant had no standing to claim compensation for any acts or omissions allegedly committed by the authorities in the course of the investigation.

It should furthermore be noted that the courts had not found the search to be lawful and had rejected it on the grounds that it had no relevance for this case. Despite the fact that the rights of the individual had been violated, he had been unable to receive compensation since it was stated that this was possible only where proceedings were terminated on exonerating circumstances [реабілітуючи обставини).

The European Court of Human Rights therefore found that the search had been carried out unlawfully and that there had been a violation of Article 8. The Court also found that the lack of a national effective remedy against violations of this right constituted a violation of Article 13 of the Convention.

5. Other aspects of privacy and respect for family life

In cases involving adoption, Ukrainian legislation does not take the interests of the adopted child into consideration. Confidentiality of adoption is guaranteed by the fact that the adoptive parents may register themselves as the child’s biological parents (Article 229 of the Family Code), change the information about the place of birth within 6 months of the child’s birth (Article 230 of the Family Code), while disclosure about a case of adoption is subject to criminal liability. (Article 168 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine). However the right of a child to know his or her biological parents (Article 7 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child) and the right to preserve his or her identity (Article 8 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child) are entirely forgotten. Even more, the law contains provisions for keeping the adoption secret from the child him or herself. (paragraph 2 of Article 226 of the Family Court).[32].

The issue continues to be problematical of the compulsory medical examinations, as well as the intrusion of law enforcement agencies into the family lives of people with non-traditional sexual orientation. For example, law enforcement agencies continue to notify the State Committee of Statistics about people they know to be homosexuals, and keep a register of them as a group at risk of AIDS.[33] In response to a formal request for information from the Vinnytsa Human Rights Group, the MIA officially notified that in 2005 131 homosexuals in Ukraine had been “identified” (!).

There are also problems with compulsory medical procedures, for example, centralized vaccination of children. If children don’t have such vaccinations, they are not accepted in a school or kindergarten. Yet the actual vaccination procedure is not without controversy. At present, the Ministry of Health carries out 12 such compulsory vaccinations and is planning to considerably increase this number.

There was also discussion in the media about voluntary medical examinations for people entering into marriage. In this case the voluntary nature of such examinations is stipulated[34]. In practice, however, sometimes no choice is given, and some public officials have spoken of possibly making such examinations compulsory.

The State Department of Ukraine for the Execution of Sentences on 25 January 2006 issued Order No. 13 “On approving instructions for checking the correspondence of people held in penal institutions and pre-trial detention centres”. Item 1.7 of this Order states that the envelope of outgoing letters should have the full address of the penal institution stamped on it. This is in our view an excessive restriction on the right to privacy both of prisoners and of their families. For example, a father will no longer write to his son from penal institution if the son is doing his military service.

In cases involving the application of Article 8 of the European Convention brought against Ukraine, violations of the right to ones own name, this being a part of the right to privacy, warrant mention. These issues were reviewed by the Court in the case of Bulgakov v. Ukraine which the European Court of Human Rights declared admissible on 22 March 2005. On 6 September 2005 the Verkhovna Rada passed in its first reading a draft law “On changing an individual’s name” (No. 7356 from 13 April 2005), however on 2 November 2006 this was withdrawn without any cogent reasons being provided.

During 2006 UHHRU received numerous complaints from prisoners saying that they were unable to get divorced or married while serving terms of imprisonment. According to legislation, to do this, people need to personally turn up with their identification documents at the State Register Office. This is clearly not possible for prisoners. At the same time the Register Office refused to go to penal institutions, while the penal administrations refused to take prisoners under escort to them. This situation is a violation of the right to marriage and family life.

UHHRU addressed an appeal to the Ministry of Justice requesting that the situation be resolved via normative acts regulating the work of the State Register Office. The Ministry entirely agreed and acknowledged the problem, however said in their response that the laws needed to be changed, “for which the preparation of the relevant draft has begun”. Almost a year has passed and there is still no sign of such a draft law.[35]

6. Recommendations

1) Adopt a law “On personal data protection” complying with modern European standards for the protection of privacy.

2) Ratify the Convention of the Council of Europe No. 108.

3) Pass a law “On interception of telecommunications” which will allow for independent monitoring of the activities of the Security Service of Ukraine in intercepting communications, publishing an annual report with depersonalized information regarding the interception of information from communications channels in the course of investigative operations. Remove generalised data on investigative operations from the “List of Items of information which constitute state secrets”.

4) Introduce amendments to legislation clearly stipulating in procedure for interception of communications (wiretapping of landlines and mobile telephones, surveillance of electronic mail, control over checks on information on the Internet), the following: ):

- Procedure for court warrants for such activities and the time limits they are valid for;

- Procedure for periodic review by the court of the warrant issued;

- Information to the person about communications having been intercepted after the procedure is over and a decision has been taken not to institute or to terminate criminal proceedings;

- The right of an individual to appeal against these actions and demand compensation if the actions of the authorities were unwarranted;

- Procedure for storage and later use of the data obtained.

5) Ensure that a Single State Automated Passport System is only introduced on a legal basis and taking into consideration the provisions of the Convention of the Council of Europe No. 108. The preparation of documents confirming citizenship of Ukraine, the creation of a SSAPS, and other activities involving confidential information, must only be carried out by government agencies.

Legislation on automated processing of personal data must reflect the following principles:

- different codes (databases of different authorities)must be used separately, and not allowing a SINGLE code for gathering all information about a person;

- a person must know what information is being gathered on any given database and have the right to change that information;

- the codes must be used ONLY for those purposes for which they were created;

- their use must be allowed for in the Law on protection of personal information;

- exchange of information gathered between the authorities must be clearly regulated. and carried out on the basis of a court order with the person both notified and able to appeal against the actions.

6) Stop the practice of illegally using taxpayers’ identification codes for other purposes than those stipulated by law.

7) The Ministry of Internal Affairs must stop the unwarranted collection of sensitive personal information about individuals (information regarding their political views, religious beliefs, sexual orientation, etc)

8) Stop the intrusion of state executive bodies into the activities of those involved in providing Internet services by forcing them to install equipment for the interception of telecommunications.

9) Abolish the licensing of IP-telephone systems.

10) Introduce amendments to legislation setting out separate divorce and marriage procedure for prisoners.

11) Pass a law and other normative legal acts protecting the rights of patients, in particular as regards compulsory medical procedure and confidentiality of information about a patient’s condition.

12) Establish procedure in criminal proceedings making it possible to appeal against the actions of law enforcement agencies in searching a person, his/her home or workplace, as well as providing the possibility of seeking redress if this procedure is infringed.

13) Change legislation on keeping adoption information secret even from the child involved.

14) Change Order No. 13 of the State Department of Ukraine for the Execution of Sentences from 25 January 2006 “On approving instructions for checking the correspondence of people held in penal institutions and pre-trial detention centres”, removing the requirement to place the full address of the penal institution on the envelope of outgoing mail.

[1] Prepared by Volodymyr Yavorsky, UHHRU.

[2] „Human Rights in Ukraine – 2004. – Kharkiv: Folio, 2006 (see the section on Privacy) http://khpg.org/en/1160759402

[3] SBU Press Centre information for the press from 2 October 2006, it is available on the SBU website (in Ukrainian):: www.sbu.gov.ua.

[4] SBU Press Centre report from 20 December 2006: www.sbu.gov.ua.

[5] SBU carries out searches of its subdivisions // UNIAN news agency: www.unian.net

[6] SBU Press Centre report from 24 May 2006: www.sbu.gov.ua.

[7] The Prosecutor General has checked out whether the Security Service wiretapped politicians // http://ua.proua.com/news/2006/09/12/121530.html

[8] Yevhen Zakharov:: “Investigative activities and privacy of means of communication”, available in English at: www.khpg.org.ua

[9] Prava Ludyny [Human Rights], No. 28, 1-15 October 2005

[10] New Item 4.4.8 of the “List of Items of information which constitute state secrets” (the amendments were passed by SBU Order №440 from 12.08.2005), classifies statistical information about investigative operations.

[11] Interview given by the Head of the Security Service of Ukraine Ihor Drizhchany on Oleksandr Kolodiy’s programme “First-hand details” on the television channel “Inter” on 7 November 2006. Available in Ukrainian on the SBU website www.sbu.gov.ua.

[12] Address given by the Minister of Internal Affairs V. Tsushko at a plenary session of the Verkhovna Rada on 23 February 2007 with regard to the situation in the Ministry of Internal Affairs // http://mvsinfo.gov.ua/official/2007/02/230207_2.html.

[13] Draft Law from 06.10.2006. No. 2288, tabled by National Deputy V.D. Shvets.

[14] The Internet publication “Maidan” http://maidan.org.ua/static/news/1113766876.html.

[15] The full text of the response is available at the UHHRU site: http://helsinki.org.ua/index.php?id=1132741095

[16] Judgment of the European Court of Human Rights from 2 November 2006 (No. 23543/02) The spelling of the names of people and places is that of the Judgment. Since some parts of the text are from the Judgment, but there are differences or omissions, the numbers of the ECHR document are only given where there is a large jump – translator)

[17] Equivalent of USD 7,045.09 in 1996

[18] see, mutatis mutandis, Klass and Others v. Germany, judgment of 6 September 1978, Series A no. 28, p. 21, § 42

[19] The law mentioned here Про оперативно-розшукову діяльність is also referred to in this text and elsewhere as the Law on Investigative Operations (translator)

[20] (see the Malone v. the United Kingdom judgment of 2 August 1984, Series A no. 82, p. 32, § 67, reiterated in Amann v. Switzerland [GC], no. 27798/95, § 56, ECHR 2000‑II):

[21] See the Klass and Others judgment cited above, pp. 23-24, §§ 49-50

[22] See the Klass and Others judgment cited above, pp. 25-26, § 55

[23] Draft Law No. 808 from 25.05.2006 (from 10.01.2003 No. 2618 prior to the 2006 parliamentary elections). Authors: M. Rodionov, S. Nikolayenko, I. Yukhnovsky and P. Tolochko).

[24] MIA Public Relations Department http://mvsinfo.gov.ua/official/2005/03/031805_1.html

[25] Draft law from 14.09.2006. No 2170. The authors were V. Tsushko, A. Semynoha, M. Onishchuk and othersі.

[26] More information available on the UHHRU website (in Ukrainian) http://helsinki.org.ua/index.php?id=1130842348, http://helsinki.org.ua/index.php?id=1128526519.

[27] SBU Press Centre report from 2 October 2006 // www.sbu.gov.ua. See also: : http://ssu.gov.ua/sbu/control/uk/publish/article?art_id=58025&cat_id=39574.

[28] Svitlana Poberezhets was represented in court by UHHRU lawyer Viacheslav Yakubenko and coordinator of the Vinnytsa Human Rights Group Dmytro Groisman. The case was supported by the UHHRU Legal Aid Fund for Victims of Human Rights Abuse which receives financial support from the International Renaissance Foundation. More information is available in English at: http://khpg.org/en/1156207989 and

http://khpg.org/en/1154644514.

[29] Judgment of the European Court of Human Rights from 29 June 2006 (No. 11901/02).

[30] 2,315 euros (EUR)

[31] EUR 165

[32] The right to respect for personal and family life: civil and legal aspects in Ukrainian legislation and court practice (in Ukrainian). Y. Petrova. The European Convention on Human Rights: Main provision and practical application, the Ukrainian context/ edited by O.L.Zhukovska. – Kyiv: “BIPOL”, 2004, p. 403

[33] The Report on the results of the work of law enforcement bodies in fighting prostitution, in identifying high-risk groups and the results of their testing for AIDS, approved by Order of the State Department of Statistics from 10 December 2002 No. 436

[34] Cabinet of Ministers Resolution No. 1740 from 16 November 2002.

[35] More details available in English at: http://helsinki.org.ua/en/index.php?id=1157539114 .