Opposition journalist facing political persecution is in danger of extradition from Ukraine to Kazakhstan

Zhanara Akhmet, an opposition journalist and solo mother, is in immediate danger of being forcibly taken from Ukraine to Kazakhstan, where she would almost certainly face torture and political persecution. This follows a cassation appeal ruling by Ukraine’s Supreme Court and arguments which could just as well be used by Russia to justify its persecution of almost 100 Ukrainian political prisoners.

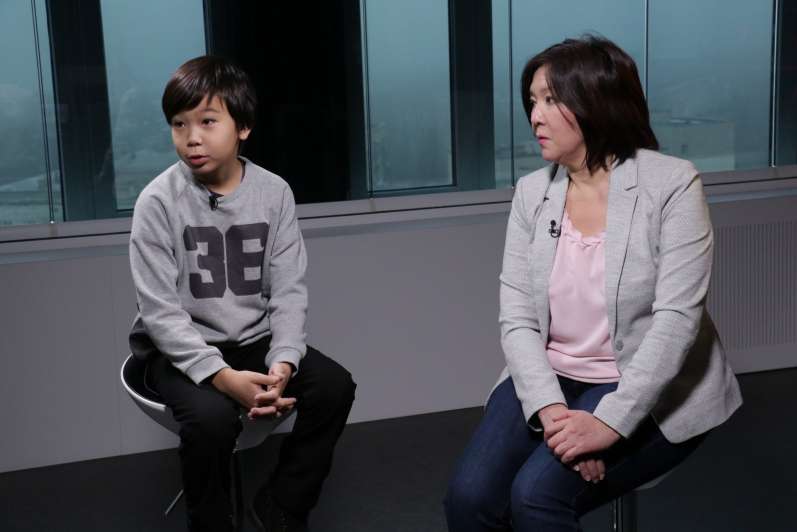

On 14 May, the Supreme Court Cassation Chamber revoked a ruling by the Sixth Administrative Court of Appeal in Kyiv which had obliged Ukraine’s Migration Service to once again review its refusal to consider Akhmet’s asylum application for herself and her son. The Migration Service instead lodged a cassation appeal which was granted in full on 14 May by the final level court, whose ruling cannot be appealed. Akhmet’s lawyers are now planning to apply to the European Court of Human Rights to apply Rule 39, to stay extradition until her case can be reviewed. The situation is especially critical since she is alone with her 12-year-old son.

The Migration Service was behaving to form when it stubbornly refused to accept that Akhmet faced political persecution. In various other cases, migration officials have often seemed oblivious to the widespread use of criminal charges against political opponents, including the use made by Moscow in its persecution of Crimean Tatars and other Ukrainians in occupied Crimea and Russia. It is frustrating that the Supreme Court allowed this line of argument, despite an appeal from prominent human rights organization and considerable evidence that it is Akhmet’s opposition activities that have activated the Kazakhstan authorities. Very worryingly, the court sat without Akhmet and / or her lawyers being present.

The human rights NGOs had condemned the Migration Service for shutting its eyes to the political context behind Akhmet’s prosecution, and warned that Ukraine would be in violation of international law by extraditing her. Fellow opposition activists in Kazakhstan have also taken the courageous step of issuing a public plea to Ukraine’s leaders to not hand Akhmet over to certain persecution.

Akhmet is a journalist and also one of the leaders of the opposition movement ‘Democratic Choice for Kazakhstan’. Although the Kazakhstani authorities are claiming that their prosecution is in connection with a 7-year sentence from 2009 for ‘fraud’, that sentence had been deferred until her son turns 14 (in 2021). In fact, the sudden decision to drop this deferment and other facts appear to confirm that Akhmet is being persecuted for the journalist and opposition activities that she has been engaged in since 2013. At the beginning of 2017, for example, Akhmet faced three administrative prosecutions and fines for supposed “publications on Facebook of calls to an unauthorized protest”. It was these evidently political prosecutions that were used as the excuse for cancelling the deferment on her sentence.

In March 2017, Akhmet and her son, Ansar arrived in Ukraine and asked for political asylum. The Kazakhstani authorities then declared her on the wanted list over the 2009 sentence.

On 21 October, 2017, in circumstances that raised concern and made Akhmet fear plans to abduct her and take her by force to Kazakhstan, the journalist was taken into custody.

During the detention hearing on 24 October 2017, the prosecutor produced a decision from the Migration Service rejecting her application for asylum. This was dated 18 October 2017, though neither she nor her lawyer had been informed of it. 2 November, 2017, an application from an MP Svitlana Zalishchuk and the Executive Director of the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, Oleksandr Pavlichenko for Akhmet to be released on their guarantee was rejected, and the prosecutor’s demand for the full period of extradition arrest allowed. There were distressing scenes in court with Akhmet’s son trying to hug his mother through the glass box that she was held in.

It took until 22 November for the Kyiv Court of Appeal to allow Akhmet’s appeal against the extradition arrest. She was released from custody, with Zalishchuk and UHHRU’s Oleksandr Pavlichenko acting as guarantors.

On 9 January 2018, the Kyiv District Administrative Court allowed Akhmet’s application to have witnesses from Kazakhstan questioned during the appeal against the Kyiv Regional Migration Service’s refusal to grant Akhmet refugee status.

Nonetheless, on 6 April the same court rejected Akhmet’s suit against the Migration Service for refusing her refugee status. Akhmet told Detektor Media that the court hearing had lasted over two hours, during which, in her view, they provided ample proof that she faced political persecution in Kazakhstan. The court took 10 minutes to reject this, asserting that the reason why she had left Kazakhstan was not political and there were no threats.

In September 2018, Zalishchuk reported that Ukraine’s Supreme Court had found the refusal of the Migration Service in her case unlawful. Although Zalishchuk said that they had ordered the Migration Service to grant her asylum, the Court did in fact only oblige them to reconsider their case. This they, purportedly, did, only to again repeat their rejection of her asylum application on 22 December 2018. It failed to even consider the facts that had been mentioned at appeal level and by the Supreme Court.

Akhmet applied to the court for a new review of her application, but this was rejected on 19 September 2019.

It had been hoped that the Migration Service would finally comply with the ruling of the appeal court on 25 February 2020, and this new ruling is a blow – for Akhmet and her son, and for Ukraine, since the latter’s reputation will be seriously stained if it extradites the opposition journalist.

In their appeal, Ukrainian NGOs, including UHHRU and the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, pointed out that Akhmet’s movement, the Democratic Choice of Kazakhstan, was labelled an ‘extremist’ organization by a Kazakhstan court in March 2018. A year later, in their resolution on human rights in Kazakhstan, the European Parliament spoke of the movement’s peaceful nature. The fact that the movement has been involved in only peaceful protests has not stopped the authorities from detained over six thousand people, including journalists and human rights activists.

There is every reason to believe that the Kazakhstan authorities’ attempts to get Akhmet extradited is politically-motivated, including their own words. The documents for her indictment actually call her “the leader of a banned movement”, and several Kazakhstani activists are facing criminal prosecution for reposting material from Akhmet’s Facebook page. There are equally strong grounds for believing that she would be subjected to torture if forcibly returned.