Move to sharply curtail peaceful gatherings in Russian-occupied Crimea

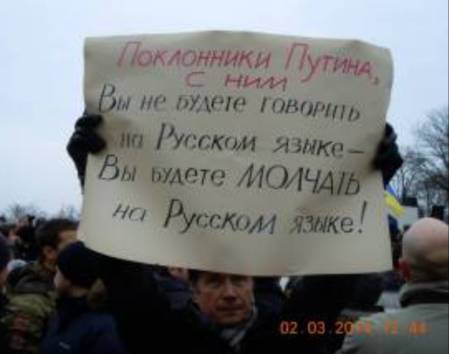

On one of the demonstrations between Russia’s invasion and ‘formal’ annexation. The words that were tragically unheeded read: “Supporters of Putin! With him you won’t SPEAK in Russian, you will be SILENT in Russian!

On one of the demonstrations between Russia’s invasion and ‘formal’ annexation. The words that were tragically unheeded read: “Supporters of Putin! With him you won’t SPEAK in Russian, you will be SILENT in Russian!

The number of places where in theory meetings can be held has halved throughout Crimea, while in some places, like Kerch, the restrictions are much more extreme.

The Crimean Human Rights Group reports that the de facto authorities in occupied Crimea have reduced the number of places in virtually every city and district where peaceful gatherings can at least in theory be held. In theory, since permission will still be required, and may be withheld. The designated places are likely to be far away and will not be seen by the people they are trying to address

In 2014 717 places were designated, where permission to hold a peaceful gathering was possible. On July 4, 2016 the so-called Cabinet of Ministers adopted a resolution, halving this number, with such meetings possible now in only 366 places. In some cities freedom of peaceful assembly has been restricted even more radically. In Kerch, for example, the number of places is now 5 times lower, and peaceful protests have been banned altogether near city authorities’ buildings.

No reason was provided.

None should be expected, since Russia under President Vladimir Putin has been systematically restricting all civil liberties over the last 16 years, including freedom of peaceful assembly.

Within months of Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea, the occupiers formally banned all public gatherings around the seventieth anniversary of the Deportation of the Crimean Tatar People on May 18. Soldiers and armed paramilitaries were present in large numbers to prevent any Crimean Tatars gathering in the centre of Simferopol where around 50 thousand people had always gathered to honour the victims of the Deportation.

Although the occupation authorities ‘allowed’ people to gather for prayer on the outskirts of Simferopol and Bakhchysarai, military helicopters ostentatiously flew overhead throughout.

There were also detentions then, and have been on subsequent anniversaries. If some other pretext is not thought up, then the participants are charged with ‘infringing the procedure for holding gatherings’.

Often, however, other grounds are used. On March 9, 2015, three Ukrainians were detained at a totally peaceful gathering to mark the great Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko’s birthday. All three were later sentenced to 40 hours’ community work, with the police officers having seriously suggested and the court accepted that Ukrainian flags were ‘prohibited symbols’.

The organizer of a small picket calling for the release of, among others, Ukrainian filmmaker Oleg Sentsov and civic activist Oleksandr Kolchenko was detained on July 13 and is now facing an administrative sentence over supposed infringement of the rules on holding rules on holding a public gathering. The video here shows how the young men were simply standing in a row with placards in defence of political prisoners.

A month earlier, on June 4, around 50 Crimeans were violently dispersed while trying to hold a peaceful protest. On that occasion, the greatest shock was probably experienced by Pavel Stepanchenko, a communist deputy in Alushta who had played an active role in supporting Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea.

He and some other protesters were clearly confused by the brutal side suddenly demonstrated by the Russian authorities they had supported. They can be heard shouting “shame on Russia” and, much less comprehensibly, calling the police violently dispersing them “Banderovtsi!”. The latter refers to supporters of the Ukrainian nationalist Stepan Bandera and has long been used in all Russian and pro-Russian anti-Ukrainian rhetoric.

It was clear from the outset that even those Crimeans who had supported Russia’s annexation had no idea what this would entail, including the effective end to civic protest.