Human Rights in Ukraine - 2005: I. The Right to Life

1. LEGAL REGULATION

The right to life is unequivocally one of the most important of all human rights. It is guaranteed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 3): «Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person». Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights also recognizes the right of every person to life, adding that this right «shall be protected by law» and that «no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of life». The right to life of those under the age of 18 and the obligation of States to guarantee this right are both specifically recognized in Article 6 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

These provisions of a universal nature should be interpreted in the context of other treaties, resolutions and declarations, adopted by UN competent bodies as well as those of regional organizations. These include in the first instance the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, Article 2 of which affirms the right to life and to protection by law of this right. The same Article stresses that “Everyone’s right to life shall be protected by law. No one shall be deprived of his life intentionally save in the execution of a sentence of a court following his conviction of a crime for which this penalty is provided by law”. Protocol 6 to this Convention establishes the abolition of the death penalty, however “a state may make provision for the death penalty in respect of acts committed in times of war or of imminent threat of war; such penalty shall be applied only in the instances laid down in the law and in accordance with its provisions. The State shall communicate to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe the relevant provisions of that law.”

On 28 November 2002 Ukraine ratified Protocol No. 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights which prohibits the use of the death penalty under any circumstances.

Here one should note that neither in Article 2 in which the right to life is affirmed, nor in Protocol 6 which sets out the requirement to abolish the death penalty, is the protection of life itself safeguarded, nor a certain standard of life. These provisions are aimed only at protecting an individual from arbitrary deprivation of human life by the state.

Point 1 of Article 2 of the European Convention affirms that ““Everyone’s right to life shall be protected by law”. In accordance with this law, member states must apply legislation that classifies as crimes deliberate killing carried out by individuals or by state officials exceeding their authority. This, however, does not mean that the state must provide personal police protection or bodyguards for individuals threatened with violence (for example, victims hunted by terrorists), or all of those living in areas of political instability (for example, in Northern Ireland).

The Constitution of Ukraine also states that «The human being, his or her life and health, honour and dignity, inviolability and security are recognised in Ukraine as the highest social value. (Article 3) and «Every person has the inalienable right to life. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of life». (Article 27).

In a Ruling from 29 December 1999, following a constitutional submission from 51 Ukrainian State Deputies asking for judgment as to the conformity with the Constitution of Ukraine (constitutionality) of the provisions in Articles 24, 58, 59, 60, 93 and 101 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine in the part which allowed for the use of the death penalty as a form of punishment (the case on the death penalty), the Constitutional Court of Ukraine declared the death penalty to be in contravention of the Constitution of Ukraine.

The right to life imposes the following duties on a state:

- to not deprive any person of life arbitrarily or where not on the basis of law (a negative duty of the state);

- to prohibit the extradition of a person to a country where they could face the death penalty;

- to prohibit the deportation of a person to a country where their life could be in danger;

- to criminalize murder and other instances involving the violent and arbitrary deprivation of life (the positive duties of the state);

- to ensure the protection of the right to life in conditions where there is a very high likelihood that a person’s life will be in danger (the positive duties of the state);

- to ensure effective and swift investigations into cases involving deprivation of life (the positive duties of the state);

2. UKRAINE’S FULFILMENT OF ITS COMMITMENTS WITH REGARD TO DEFENDING THE RIGHT TO LIFE

In the first instance, the state’s obligations should be directed at protecting citizens from arbitrary and illegal deprivation of life. This in particular concerns crimes against life: Articles 115 – 121 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (CCU).

In 2005 3194 crimes were recorded in Ukraine with criminal cases[2] being opened under Article 115 of the CCU (premeditated murder).[3] In comparison with 2004 (when 4006 cases were initiated), there was some reduction, however all this still says nothing about the effectiveness of protection in Ukraine of the right to life, especially if one takes into account the fact that the success rate of investigations into these crimes remains low.

According to information provided by the Minister of Internal Affairs, Yury Lutsenko, “in 2005 over 90% of murders and cases of grievous bodily harm resulting in death were solved”

According to statistics from the State Court Administration in 2005, criminal charges were brought against 4323 people for crimes against life, of whom:

2,031 people were charged under Article 115 of the CCU (premeditated murder);

71 people under Article 116 of the CCU (premeditated murder in a highly disturbed emotional state);

13 people under Article 117 of the CCU premeditated murder by a mother of her new-born child;

160 people under Article 118 of the CCU (premeditated murder through exceeding the bounds of necessary defence, or through exceeding the measures needed to detain a criminal;

312 people under Article 119 of the CCU (causing death through careless behaviour);

7 people under Article 120 of the CCU (driving somebody to suicide);

1729 people under paragraph two of Article 121 of the CCU (premeditated grievous bodily injuries leading to the death of the victim, or committing this as a contract crime, or in a group.

A significant problem is the reluctance of law enforcement agencies to launch criminal cases into murder. The detective enquiry is often carried out in a superficial manner, various circumstances are not taken into consideration and witnesses are not questioned. This is partly connected with the lack of desire to launch criminal cases involving murders that will be difficult to solve, and that will further spoil the general showings of the work of the law enforcement body.

There were no cases reported of politically-motivated murders committed by those in power or their agents in 2005, however the press wrote about at least four cases where people detained in custody were beaten to death.

On 7 April police officers in Zhytomyr beat to death a 36-year-old man whose identity has not been established. He had been detained on a charge of petty hooliganism. The mass media reported that the Prosecutor’s office in the Zhytomyr region had launched criminal proceedings against several police officers (the exact figure was not given)) on charges of inflicting “premeditated grievous bodily injuries " and “exceeding their authority”.

On 26 September the newspaper “Kyevskye vedomosti” [“Kyiv Gazette”] reported that a person suspected of theft had been beaten to death in the city of Kherson. The newspaper noted also that the police officer implicated had been detained.

At 4 in the morning on 8 December police officers from the Chervonozavodsky District Police Station

In Kharkiv detained Oleh Dunich and took him to the station from where, at 8 a.m. he was taken by ambulance to a hospital where he died a day later from injuries incompatible with life[4].

According to reports in the mass media, on 17 December in the Kharkiv pre-trial detention unit, 21-year-old Armen Melkonyan, whose case was under investigation, was beaten to death.[5] The press wrote that the head of the unit, Serhiy Tkachenko, was attempting to cover up the incident. High-ranking officials of the Kharkiv region informed representatives of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group (KHPG) of the results of the autopsy which confirmed that Melkonyan had died as a consequence of physical violence, which contradicted the assertions of Tkachenko who claimed that the young man had died of natural causes. The immediate cause of death was “asphyxiation through blockage of the respiratory tract due to vomiting”. In addition, the results of the court medical investigation indicated that Melkonyan had suffered serious head injuries. Following insistent demands from KHPG and the relatives of the deceased man, on 23 December the Prosecutor’s officer finally launched a criminal investigation.

No progress was recorded in the case involving the death of resident of the city of Melitopol, Mykola Zahachevsky who died in suspicious circumstances in April 2004 while remanded in custody pending trial.

One should note that fatal incidents continue to occur in the army although officials claim that no military serviceman has died as a result of physical violence. The Ukrainian Ministry of Defence stated that over 6 months of 2005 6 servicemen had committed suicide while carrying out military service duties. The Ministry of Defence notes in this respect that there is a clear trend towards a decrease in the number of such cases[6].

In spite of the fact that army officials talk about the lack of cases of deaths as the result of physical violence among military servicemen, the Union of Soldiers’ Mothers of Ukraine (USMU) are convinced that violence in the army remains a widespread occurrence and report that one conscript from the Zhytomyr region who was doing his military service in Kyiv was beaten to death during just such an incident in January 2005.. Those who are senior often beat up new conscripts and take their money away, as well as things they’re sent from home – the malaise known as “didovshchyna”. According to the USMU, the army prosecutor’s office frequently do not react to complaints about such bullying, accept bribes to not interfere, procrastinate with beginning a review of the case or wait until the culprits are demobilized. The USMU also draws attention to the at least three cases – in the cities of Simferopol, Luhansk and Sumy, when the efforts of the army prosecutor led to servicemen who had complained about bullying being placed in psychiatric hospitals.[7]

There is no evidence of the new leadership’s intention to continue investigations into a number of murders committed under Kuchma’s regime which formed the grounds for accusing the latter of implication in criminal activities. Law enforcement agencies have refused to provide either the public, or a special parliamentary investigative commission with any supplementary information regarding the death in August 2003 of the deputy leader of the “Ukrainska narodna partiya” [“Ukrainian People’s Party”], Ivan Havdydy. There is no indication whatsoever that the law enforcement agencies are looking into the circumstances behind the death in November 2003 of the leader of the party “Reforma I poryadek” [“Reform and Order”] in the Khmelnytsky region, Yury Bosak, who was found hanging from a tree in a forest. His death was recorded as suicide The Prosecutor General of Ukraine is continuing to avoid investigating the circumstances behind the death in December 2003 of Volodymyr Karachevtsev, the head of an independent union of journalists in Melitopol, and the deputy chief editor of the independent newspaper “Kuryer” [“Courier”]. Volodymyr Karachevtsev, who had on many occasions written about the corruption of local officials, was found with a noose formed from a sweater around his neck and attached to the handle of the refrigerator. Despite clear evidence rejecting the version of suicide, the local authorities claim that the journalist took his own life.

By the end of the year there had still been no verdict into the case involving the murder in 2001 of the director of one of the regional television channels in the Donetsk region, Ihor Aleksandrov. This crime remains at the centre of public attention. According to reports in the media, the court review into Aleksandrov’s murder is continuing as are attempts to mislead the investigation. There are twelve people who are accused of various crimes in connection with the case. Following a ruling from the Supreme Court which expressed no confidence in the Donetsk Regional Court where hearings into the Aleksandrov case had begun, the matter was passed to the Luhansk Appeal Court. The murder of Ihor Aleksandrov, who had broadcast a number of critical feature items regarding Donetsk politicians, and had actively criticized corruption in local law enforcement agencies, is believed to have been linked with his professional activities.

During the year several serious steps were taken in the investigation into the still unsolved murder of Georgiy Gongadze. The prominent journalist’s beheaded body was discovered in November 2000, two months after he disappeared. On 2 March 2005 the Prosecutor General announced that three police officers who had taken part in Gongadze’s abduction had been arrested and that they had given a detailed account of the circumstances around the journalist’s murder. Their trial was scheduled for January 2006. The Prosecutor General also stated that a fourth high-ranking accomplice to the crime, Police General Oleksiy Pukach, who had left Ukraine, had been placed on the international wanted list. Government sources also informed that on 4 March the former Minister of Internal Affairs, Yury Kravchenko, had shot himself at his home in Kyiv on the day that he was supposed to appear for questioning over his role in the Gongadze case. Despite the fact that two gunshot wounds to the head were found, the official version remains that Kravchenko committed suicide. The opinion expressed by the media and by Gongadze’s widow is that it was specifically former Minister Kravchenko who, carrying out the instructions of the then President, Leonid Kuchma, gave the instruction to have Gongadze murdered. Those, however, who ordered the killing remain unknown, and a proper investigation into their search is still not being carried out.

Meanwhile the European Court of Human Rights in a Judgement from 5 November 2005 in the Case of Gongadze v. Ukraine unanimously agreed that the Ukrainian authorities had on several occasions violated the rights of the journalist’s widow, Myroslava Gongadze. They had not, for example, protected Georgiy Gongadze’s life, and the investigation into the circumstances around his death had been inadequate.

“178. The Court observes that the applicant maintained that the investigation into the disappearance of her husband had suffered a series of delays and deficiencies. Some of these deficiencies were acknowledged by the domestic authorities on several occasions.

179. The Court considers that the facts of the present case show that during the investigation, until December 2004, the State authorities were more preoccupied with proving the lack of involvement of high-level State officials in the case than by discovering the truth about the circumstances of the disappearance and death of the applicant’s husband”.[8]

The Court also accepted the lack of effective remedies in Ukraine for protecting the right to life in this case in the understanding of Article 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

The European Court of Human Rights thus found that Ukraine had violated Articles 2, 3 and 13 of the European Convention, and bound it to pay Myroslava Gongadze 100 thousand Euros in respect of pecuniary and non-pecuniary damage.

The results of a drawn-out parliamentary investigation into the case were made public in the Verkhovna Rada on 20 September by State Deputy, Georgiy Omelchenko.

Indeed, from a human rights point of view, this case is a classic example of methods of stalling and of the ineffectiveness of law enforcement agencies in murder investigations.

In February, April and May leading newspapers again ran articles suggesting that a special unit of law enforcement officers, known as “perevertni”[9] had been implicated in the abductions and murders committed in previous years. There was no sign that such assertions were actively investigated.

Politicians and politically engaged businesspeople and journalists have been subjected to forms of pressure, sometimes resulting in their death or serious damage to their health, with political overtones. At the same time, business, politics and crime are so closely intertwined in Ukraine that it is often difficult to ascertain the true motives for a crime. For example, on 20 November the press reported that the former governor of the Lviv region, Stepan Senchuk had been shot by unidentified individuals, probably hired killers, in one of the villages on the outskirts of Lviv. Senchuk, a businessman, had joined the People’s Union Our Ukraine [Nasha Ukraiпa] at the beginning of the year.

A no less important aspect of protecting the human right to life is investigations into disappearances. In 2005 there were no reports of any politically motivated disappearances. It should, however, be noted that there was no progress in the investigation into the disappearance in December 2003 of Vasyl Hrysyuk, a journalist from the newspaper “Narodna sprava” [“People’s matter”] which is published in the district centre, the town of Radekhiv, in the Lviv region. By the end of the year there was still no sign that the case was being actively investigated.[10]

The European Court of Human Rights reviewed several cases against Ukraine in 2005 involving violation of the right to life. On 28 June 2005 the Court postponed review of the merits in the case lodged by Serhiy and Svitlana Khailo (application No. 39964/02), in which the applicants complain about the lack of an effective and independent investigation into the death of the brother of one of the applicants.

In the case of Tetyana Petrivna Muravska against Ukraine (Application № 249/03), the Court decided on 13 September to defer judgement on the grounds of insufficient information. In this case the applicant’s case is over the ineffective and clearly drawn-out investigation into the murder of her son, who disappeared on 23 January 1999. On 1 February she learned that he had been beaten up and that he had died as a result of his injuries. His body was found in a lake on 18 March 1999. The next day a forensic medical examination was called, however the forensic expert claimed to be unable to establish the cause of death, saying that the person at the time he died had been intoxicated. Since then the applicant has been trying to have criminal proceedings initiated against the forensic expert for issuing a manifestly untruthful medical expert assessment. The Prosecutor on 26 March refused to institute a murder investigation. These decisions were later revoked. A supplementary investigation on 11 November 1999 established that the person had been killed. From then on there were numerous forensic medical examinations. The applicant therefore, in March 2005, tried to bring a suit against the actions of the investigators in the Voroshilovsky District Court in Donetsk. The Court however refused to admit her claim. This refusal was challenged in the Donetsk Region Appeal Court. The Prosecutor General on 8 April 2005 stated that the investigation into the case was being delayed because forensic medical examinations had still not been completed. The examinations in this case had thus lasted 6 years (!).

Within the framework of the Fund for the Protection of Victims of Human Rights Violations (strategic litigations) the UHHRU provided legal aid in a case involving the death of an employee of the law enforcement agencies in the city of Kovel in the Volyn region. The dead man’s widow had been refused access to the material in the criminal case. In addition, the conclusions of the forensic medical examination also seemed somewhat questionable. At the present time the case is being considered by the Volyn Regional Appeal Court.

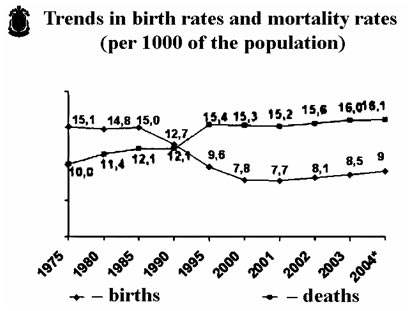

An important part of safeguarding the rights of individuals to life is providing an efficient system of health care, a safe environment and other aspects which can pose a real threat to life. In this respect, it is worth considering the general trends as regards the birth rate and mortality rate, as well as the main factors in the mortality figures in Ukraine.

The European Court of Human Rights on 10 January 2006 refused to admit the application of Svitlana Volodymyrivna Pronina (Application No. 63566/00) in the part asserting violation by Ukraine of Article 2 of the European Convention (the right to life) in which the applicant claimed that the size of her pension which was her sole means of existence, presented a threat to her life. In this case the Court stressed that the right to life did not guarantee a particular standard of living[11] and said that the application had not proven that this really did place her life in direct danger.

The program of the present government gives issues of health care an appropriate place since it proclaims “the faith of citizens in the future will change as the life expectancy figures rise, the number of new births increases and mortality figures drop”

However, unfortunately, it must be acknowledged that 5 years after the publication of a Strategy Plan for the development of health care in Ukraine, there are very few positive steps in health care. This is graphically illustrated in the following figures regarding the numbers of births and deaths. .

Trends in birth rates and mortality rates (per 1000 of the population)

- births - deaths

The Mortality rate of the population broken down into causes of death and the ratio between births and deaths in Ukraine for 2003, 2004 and the first 6 months of 2005[12]

| 2003 | 2004 | January – June 2005 | |

| Deaths as a result of industrial injuries[13] | 1 874 | 1 935 | х |

| Deaths as a result of domestic injuries | 71 534 | 70 354 | 35 082 |

| Murders | 5 267 | 4 989 | 2 332 |

| Suicides | 12 322 | 11 259 | 5 455 |

| Infant mortality in the first year of life | 3 882 | 4 024 | 2 068 |

| Death from tuberculosis | 10 421 | 10 787 | 6 387 |

| Death from HIV/AIDS | 1 831 | 2605 | 1716 |

| Births | 408 589 | 427 259 | 204 081 |

| Deaths | 765 408 | 761 261 | 413 403 |

| Ratio of births and deaths (how many born per 100 deaths in %) | 53,4 | 56,1 | 49,4 |

3. RECOMMENDATIONS

1 To change criminal procedure legislation in order to provide more rights to victims, including to the families of those killed, and to increase their impact on the course of the investigation;

2 To introduce effective independent mechanisms for investigating deaths, especially those caused by the actions of law enforcement officers and the staff of medical institutions;

3 To publish an annual report on investigations into crimes against life;

4 To ensure the availability of independent forensic medical examinations for assessing causes of death.

5 To pass a Law of Ukraine “On patients’ rights” providing safeguards for the observance of patients’ right to life.

[1] Prepared by Volodymyr Yavorsky and Maksim Shcherbatyuk, UHHRU

[2] In Ukrainian launching a criminal case (kryminalna sprava) may correspond to either launching a criminal investigation or actually beginning criminal proceedings. Where this may not be clear, and in cases where the authorities are refusing to acknowledge a crime per se, we use “case”. (translator’s note)

[3] Letter from the Ministry of Internal Affairs on the number of cases solved under Article 115 of the CCU from 4 April 2006. Available on the “Maidan” website: http://maidanua.org/static/news/1144564489.html.

[4] More detail about this case can be found in Section II (translator’s note)

[5] V. Chystylin: “Emergency on a city scale” // The newspaper “Bez tsenzury” [“Without censorship”] No. 1, 12 January 2006

[6] A letter from the Central Department of military service of law and order in the Armed Forces № 306/ІАС/87 from 11 January 2006 in response to a formal request for information.

[7] Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the US State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, March 8, 2006

.

[8] The Judgement of the European Court of Human Rights from 8 November 2005 in the case Gongadze v. Ukraine, is available in Ukrainian on the Ministry of Justice’s official site: http://minjust.gov.ua. In English it can be found at: www.echr.coe.int

[9] “Pereverten”, literally a “werewolf” is a word used about police officers and the like who use their position to engage in corrupt and criminal activities (translator’s note)

[10] Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the US State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, March 8, 2006

[11] See the Case of the European Court of Human Rights Wasilewski v. Poland, no. 32734/96, 20 April 1999

[12] Letter from the State Committee of Statistics No. від10/2-2-8/415 from 26 September 2005 in response to a formal request for information.

[13] Either from accidents recognized as connected with industry, or those which took place at plants, etc, but were not connected.