• Topics / Human Rights Abuses in Russian-occupied Crimea

Ukrainian Orthodox Church in occupied Crimea under imminent threat following Russian Supreme Court decision

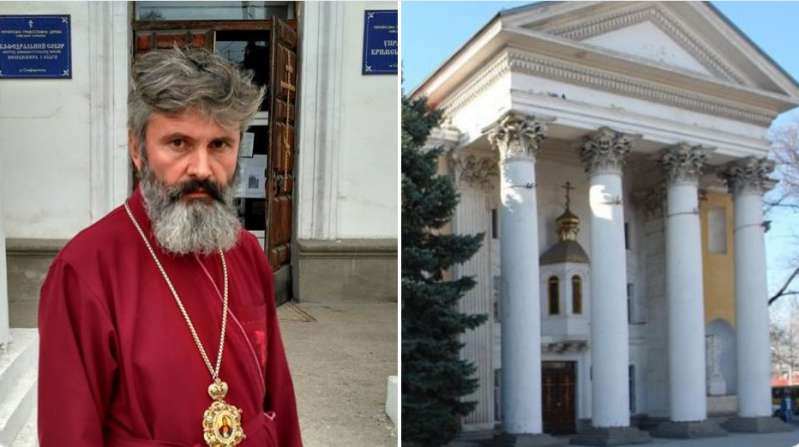

A week after Archbishop Klyment was threatened with criminal prosecution if he did not demolish a Ukrainian Orthodox chapel in Yevpatoria, Russia’s Supreme Court has taken a decision which places in jeopardy the very existence of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in occupied Crimea. On 4 August 2020, the Supreme Court refused to reconsider the decision to evict the congregation of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine from the Cathedral of St Vladimir and Olga in Simferopol which Russia has been trying to take over since its invasion and annexation in 2014.

Serhiy Zayets, the lawyer representing the Ukrainian Orthodox congregation, reported the decision saying that it is time to sound the alarm. The Supreme Court’s decision, he believes, “essentially means the total dissolution of the Ukrainian Orthodox community in Crimea. This is not formally genocide, but it borders on it. Russia is destroying yet another Ukrainian religious and cultural group and is continuing to purge Crimea of all that is Ukrainian”.

Archbishop Klyment has long warned of the danger and of the consequences if Russia is allowed to destroy the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Crimea. In December last year, the warning was stark: “If there is no Diocese and no Cathedral (of Saints Vladimir and Olga), it will not be possible to speak of anything Ukrainian having been preserved in Crimea.”

This is, unfortunately, exactly what Russia is seeking to achieve, and it is no accident that it was the Ukrainian Orthodox Church that first came under pressure from the occupation regime. It is immensely frustrating that the Ukrainian government has been so slow to take measures aimed at protecting the Church and Ukrainian believers under occupation.

With Russia systematically trying to eliminate any elements of Ukrainian identity from occupied Crimea, it was inevitable that the Ukrainian Church should have become for many Crimeans a place they could come to hear, speak and to worship in Ukrainian. Klyment recently spoke of the Church having become the only island of Ukrainian identity and spirituality on the occupied peninsula.

The Archbishop has said that, despite many Ukrainians having left for mainland Ukraine, the number of believers has not significantly fallen, with new people, some of them not ethnic Ukrainians, but clearly feeling Ukraine to be their homeland, joining the congregation.

It is this Ukrainian identity which Russia has sought to eliminate. It is, however, likely that the Church and its Archbishop were also viewed as ‘the enemy’ due to their openly pro-Ukrainian position and to the public statement from the Church on 11 March 2014, condemning Russian occupation of Crimea.

During the first year after Russia’s invasion, 38 out of the 46 parishes under what was then still the Kyiv Patriarchate ceased to exist. In at least three cases, churches were seized by the occupation regime: in Sevastopol; Simferopol and in the village of Perevalne.

Although western countries reacted very weakly to Russia’s invasion, Moscow probably feared a more active reaction to open persecution of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, and instead used so-called ‘reregistration’ under Russian legislation as a weapon, and set about physically removing the Church’s property.

It should be said that the Ukrainian government was much too slow to take obvious measures to protect the Church. It was only in the Spring of 2020 that the government finally took measures to officially transfer the Cathedral in Simferopol to state ownership. Although this was unlikely to change Russia’s illegal behaviour, the move was important in providing an instrument, so that Ukraine could call upon international partners and approach international courts to defend Ukraine’s Cathedral and its believers from the occupiers.

The move should have been taken immediately after annexation. Instead, since the land had under Ukrainian law, been the property of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, the Russian occupiers claimed it to be ‘federal Russian property’ which the Archbishop was illegally occupying.

The battle to seize control of the Cathedral of Vladimir and Olga effectively began soon after Russia’s invasion, with Klyment reporting that he was initially offered 200 thousand dollars to give the Cathedral up.

Then in January 2016, the Russian-controlled Crimean Arbitration Court issued a ruling ordering the Church to vacate 112 m² of the premises (the ground floor) and to pay a prohibitive half a million roubles, which were claimed to be for communal services.

The attempts to totally evict the Diocese and the congregation date back to 2019. Zayets writes that the original eviction notice was in the summer of 2019, however Klyment reported on 8 February 2019 that he had received a writ ordering that he vacate the Cathedral within 30 days. The Archbishop then warned that this was likely to lead to eight parishes in rural areas also being forced to close.

On 28 June 2019, the de facto ‘Crimean Arbitration Court’ ordered the dissolution of the lease agreement for the Cathedral signed in 2002 between the Ukrainian authorities (the Crimean Property Fund) and the Crimean Diocese of what was then the Orthodox Church under the Kyiv Patriarchate.

The real attempts to evict the Church, Zayets says, began at the end of August 2019, although they swiftly hit what should have been a formidable obstacle. In September 2019, the UN Human Rights Committee intervened, applying Rule 94 to halt the eviction of the congregation.

Russia had appeared to be hesitating, with the Supreme Court in December 2019 halting implementation of the eviction order. Zayets says that, after the same Supreme Court twice (in March and in June 2020) extended the period for consideration of the appeal, there had been some grounds for hope. There may have been some political reason for the delay, however the decision on 4 August suggests that the situation is now critical.

Reaction from both Kyiv and the international community is absolutely vital. Russia has already demonstrated its willingness to harass and even detain the Archbishop. If Moscow does not encounter real resistance from the West, the next step will almost certainly be persecution of the Archbishop and of Ukrainian members of the Church.