“They’re killing my father!” Daughter of 63-year-old Ukrainian imprisoned for opposing Russian occupation of Crimea

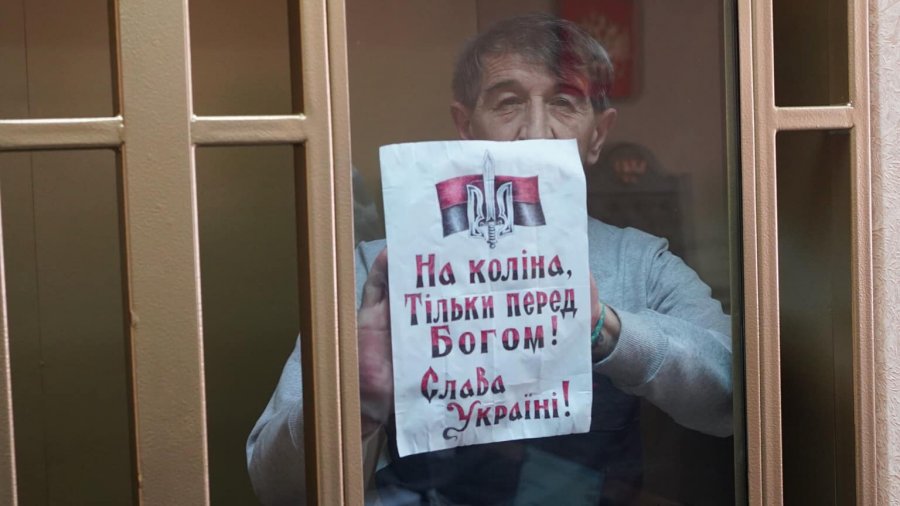

Oleh Prykhodko’s wife and daughter were allowed a three-hour meeting with the Ukrainian political prisoner on 18 January, and report that the 63-year-old is in a terrible state after torture and ill-treatment in Russian captivity. Prykhodkho’s daughter, Natalia told Crimean Realities that her father himself says that they are killing him, and that he will not get out alive.

As feared, the worst treatment appears to have been during the gruelling journey in stages from Rostov-on-Don, where Prykhodko’s ‘trial’ took place to the Vladimir Prison, one of the worst of Russia’s penal institutions. Natalia recounts that in prison colony No. 7, her father “was tortured through electric currents; had water poured over him; and was held with his arms twisted, in handcuffs”. This appears to have an attempt to torture out of him a ‘confession’ which they dictated to having, supposedly, fought in various hotspots.

After arriving at the Vladimir prison, Prykhodko was placed in quarantine in a solitary cell. There he sat and fell asleep in sitting position, for which he was then thrown into a punishment cell, where the conditions are especially bad. Natalia herself calls this silent murder, and quotes her father, who told them: “I’m being killed, and won’t get out of here. They won’t even give you my body.”

They were aghast at how shocking Prykhodko is looking. In his letters, he had not answered their questions about his state of health. Natalia assumes that if he had, the letters would simply not have got through. He is not receiving any of the medication they send, with this including medicines for his stomach and urinary system. Prykhodko complained of painfully swollen legs several months ago, and his daughter was struck by the extent of swelling. Prykhodko told them that he has complained on many occasions of pain, but the doctor simply turns up and says that everything is fine.

For several months in 2021, Prykhodko’s family and lawyers heard nothing from him at all. It was only in the second half of October, three months after Prykhodko had arrived in Prison No. 3 in Russia’s Vladimir oblast that lawyer Sergei Legostov was finally able to see him. Legostov reported that, in violation of Prykhodko’s rights, there had been a prison employee present and videoing the entire conversation. The men were also separated by a glass barrier with the connection for speaking of poor quality, which was a major problem since Prykhodko has hearing difficulties. They were stopped after 25 minutes because it was the lunch break, and Legostov was not allowed to return to continue the conversation. This was all very clearly deliberate, since Legostov himself had arrived at the gates of the prison much earlier, but had been forced to wait outside, in the rain, for two hours.

There were other violations with potentially grave ramifications. Legostov had brought important documents for Prykhodko to sign, including one about a cassation appeal against his five-year sentence, and another authorizing the lawyer to represent Prykhodko at the European Court of Human Rights. He also needed to sign a form permitting his lawyers to reveal information about medical records; personal data and his answers to questions about the prison conditions. The prison staff refused to let him hand the documents over, with this potentially meaning that they could miss crucial deadlines.

Prykhodko is one of at least three Crimeans, all with strong pro-Ukrainian views, who were arrested in the first three months after Russia’s last release of Ukrainian political prisoners.

The FSB came for Prykhodko on 9 October 2019, and charged him with planning to blow up the Saki City Administration building. Prykhodko’s open opposition to Russian occupation had already led to earlier administrative prosecutions and he had every reason to expect FSB visitations and searches, with this just one of the reasons for profound scepticism regarding the bucket with explosives that the two FSB officers claimed to have found in his garage. Another was that he is a blacksmith and metalworker by profession, who used both garages for welding and soldering work. He would have been suicidal to hold flammable substances near his equipment.

It was also telling that the officers did not want to search Prykhodko’s second garage. This would only make sense if they knew in advance that they would find nothing, because the only explosives or illegal items were those that they had brought with them. Fingerprints were allegedly not taken from the bucket, nor did the investigators ever explain how Prykhodko was supposed to have obtained items which were not freely on sale.

A few months later it became clear that the ‘investigators’ were also claiming that Prykhodko had planned to set fire to the Russian general consulate building in Lviv, Western Ukraine, with the alleged ‘proof’ of this lying in a telephone and a memory stick.

Prykhodko was charged under three articles of Russia’s criminal code: Article 205 § 1 - planning terrorist acts (supposed plans to blow up both the Saki Administration in Crimea and Russian general consulate in Lviv); Article 223.1 - illegally preparing explosive substances; and 222.1 § 1 (purchasing or storing explosives).

If the only ‘proof’ for the first charge, namely the explosives, seemed extremely suspect, that for the supposed plan to blow up the Russian general consulate was almost comically implausible. It was asserted that he had discussed, via telephone and text messages, these ‘plans’ with an unidentified individual in mainland Ukraine. Prykhodko had extremely basic knowledge of how to use both a smartphone and a computer, and would certainly have had no idea how to send a text message or use a memory stick. The defence was able to demonstrate, via billing records, that the telephone, allegedly found during the search, and the one supposedly used by the person in Lviv, had been bought in the same Simferopol shop shortly before the supposed communication. The lawyers also showed that the phone call which was supposed to have been made by this mystery individual from Lviv, during which he had hinted at Prykhodko’s purported terrorist plans, had, in fact, come from the Kherson oblast, more precisely somewhere around the administrative border with occupied Crimea. Such a call could easily have been made by the FSB, which would explain why the latter showed no wish to identify the mystery person, or to try to ascertain why the phone which was supposed to be Prykhodko’s was registered in another name altogether. The defence also produced an experiment that showed that, when a Ukrainian sim-card is used in occupied Crimea, any call or message received is seen as having come from a Ukrainian user. This means that there would be nothing to stop all of the alleged text message ‘correspondence’ having been generated in occupied Crimea.

In declaring Prykhodko a political prisoner, the authoritative Memorial Human Rights Centre also considered some phone calls allegedly recorded. These used very heated language, but gave no indication of plans to commit any specific actions. The human rights group points out that the only specific details were from the alleged text messages which could very easily have been fabricated. It was these which were found in an expert assessment to “be of a terrorist nature”.

Prykhodko was tried at the same Southern District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don (Russia) which has been involved in most politically-motivated trials of Crimean Tatar and other Ukrainian political prisoners. In December 2020, prosecutor Sergei Aidinov claimed that the charges had all been proven and demanded an 11-year sentence and fine of 200 thousand roubles. On 3 March 2021, presiding ‘judge’ Alexei Abdulmazhitovich Magomadov; together with Kyrill Nikolayevich Krivtsov and Sergei Fedorovich Yarosh, found Prykhodko guilty of all charges, however removed the charge under Article 223.1 (preparing explosives) as being time-barred. They sentenced him to five years’ harsh-regime imprisonment with the first year to be served in a prison, the worst of all Russian penal institutions. He was also ordered to pay a still prohibitive 110 thousand rouble fine. On 17 May 2021, ‘judge’ Sergei Viacheslavovich Vinnik from Russia’s military court of appeal upheld the sentence. The defence is planning to apply to the European Court of Human Rights.

PLEASE WRITE TO OLEH PRYKHODKO!

Letters send an important message, telling him that he is not forgotten, while also showing Moscow and the prison staff that people from all over the world are watching their treatment of him. Letters need to be in Russian, and on ‘safe’ subjects. If that is a problem, you could copy out the letter below, maybe attaching a photo or picture of your own. Please do give a return address, so that Oleh can reply.

Sample letter

Привет,

Желаю Вам здоровья, мужества и терпения, надеюсь на скорое освобождение. Простите, что мало пишу – мне трудно писать по-русски, но мы все о Вас помним.

[Hi. I wish you good health, courage and patience and hope that you will soon be released. I’m sorry that this letter is short – it’s hard for me to write in Russian., but you are not forgotten. ]

Address

The envelopes can be written in Russian or English as below.

600020 г. Владимир, ул Большая Нижегородская, д.67, ФКУ Тюрьма-2,

Приходько Олегу Аркадьевичу 1958 г.р.

Russian Federation, 600020 Vladimir, ul. Bolshaya Nizhegorodskaya, No. 67, Prison No. 2,

Prykhodko, Oleh Arkadiyevich, b. 1958