Russia extends terror and abductions from occupied Crimea and Donbas to all of Ukraine

Since its total invasion of Ukraine on 22 February 2022, the Russian military have been seizing Ukrainian civilians in all areas that fall under their control. In the Zaporizhzhia oblast alone, there had, as of 11 May, been 271 abductions, with 118 Ukrainians, including one child, still held hostage. This is without counting the huge number of people, especially from Mariupol, whom the Russians have taken by force to Russia or occupied parts of Donbas.

None of this should come as any surprise since Russia has been applying such methods of terror in Crimea since its invasion in late February 2014. As for Russia’s proxy ‘Donetsk and Luhansk people’s republics’ [‘D-LPR’], even before 24 February this year, a minimum of 300 civilian hostages, as well as some prisoners of war, were in captivity while others had disappeared after being seized by these Russian-controlled illegal armed formations.

In December 2021, Crimea SOS reported that there had been 44 cases of enforced disappearance in occupied Crimea, with the fate of fifteen men, including two who were very young unknown. In none of these cases have the occupation authorities taken any real measures to find the missing people and / or their abductors, almost certainly because they know perfectly well who was behind their disappearance.

It is exactly six years since, on 24 May 2016, Crimean Tatar civic activist Ervin Ibragimov was abducted by men in Russian traffic police uniform near his home in Bakhchysarai. He has not been seen since, with the Russian occupation regime not only failing to investigate the abduction, but also telling cruel, or scurrilous, lies about Ibragimov and other Crimean Tatar victims of enforced disappearances.

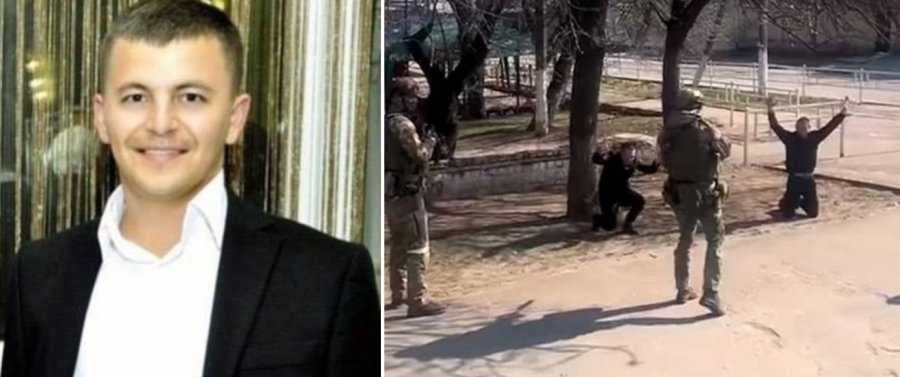

Although only 30 when abducted, Ervin had been a deputy of the Bakhchysarai City Council prior to Russia’s invasion, and was also a member of the Executive Committee of the World Congress of Crimean Tatars. He had arranged to travel in the morning of 25 May 2016 to the trial of four young men prosecuted for an event in remembrance of the victims of the Crimean Tatar Deportation.

Ervin’s father sounded the alarm the following morning after Ibragimov failed to return home. His car was found fairly near his home with the key in the ignition and door open. CCTV recordings were obtained from a shop nearby which showed Ibragimov being stopped by men in traffic police uniform. He clearly understood he was in danger and tried to flee, but was seized and forced into the men’s van.

There are several reasons for suspecting the occupation regime of being behind Ibragimov’s disappearance. The young Crimean Tatar had noticed being under surveillance before his disappearance and men in police uniform had stopped outside his home. The FSB also refused to accept the family’s official report that Ibragimov was missing and only initiated a formal investigation after hundreds of Crimean Tatars gathered outside police headquarters demanding action. Just over a year before Ibragimov’s abduction, another human rights activist, Emir-Usein Kuku had been subjected to what was probably an attempted abduction. He managed to call for help and a crowd gathered, after which the abduction turned into an FSB ‘search’ (and beating). Within a year, Kuku had been arrested on preposterous ‘terrorism’ charges and is now a recognized political prisoner and Amnesty International prisoner of conscience..

Timur Shaimardanov was 33 when he disappeared on May 26 2014. A civic activist, he had been actively involved in peaceful protest against Russia’s annexation of Crimea and had been taking food and cigarettes to trapped Ukrainian soldiers. 33-year-old Seiran Zinedinov disappeared a week after Shairmardanov, on May 30. Vasyl Chernysh, an Automaidan activist from Sevastopol was last seen on March 15, 2014, the day before the so-called ‘Crimean referendum’. Ivan Bondarev and Valery Vashchuk were both young Maidan activists in their early 20s. They disappeared in Simferopol on 7 March 2014, having phoned their families and said that they had been detained by ‘the police’.

Islam Dzhepparov was just 19 when he was abducted in Crimea on 27 September, 2014, together with his 23-year-old cousin Dzhevdet Islamov. Despite the fact that they were seen being forced into a dark blue Volkswagen Transporter and taken away in the direction of Feodosia, and that the police even had the minivan’s registration number, neither the young men, nor their abductors have ever been found.

With respect to the abduction, savage torture and killing of Reshat Ametov, everything is known, yet nothing has been done to punish the perpetrators, despite clear video footage of his abduction. The 39-year-old Crimean Tatar father of three, was abducted by pro-Russian paramilitaries in on 3 March 2014 from his lone picket in protest at Russian occupation outside the Crimean parliament. His badly mutilated body was found almost two weeks later.

Russia is claiming that Crimea is part of its territory, with this probably why the number of enforced disappearances is not higher. Instead, however, there are an ever-increasing number of Crimean Tatar or other Ukrainian political prisoners, with the figure already over 130.

Moscow has constantly denied direct control over the so-called ‘D-LPR’ and tried to foist the idea that the conflict in Donbas is a ‘Ukrainian civil war’. It is frustrating that so many western media continue to talk about ‘separatists’, since Russia has manned, armed and totally financed these illegal armed formations since 2014.

The methods now used by the Russian military against local leaders, civic activists, journalists, etc in areas that have fallen under their control are essentially identical to those used by the proxy ‘republics’ since 2014. Many hostages have simply vanished, with their whereabouts becoming known only thanks to those few hostages who have been part of an exchange. While in a number of cases, people have probably been taken hostage in order to extract ransom, to steal their property, or similar, on many other occasions, people have been seized and savagely tortured at the Izolyatsia secret prison in Donetsk, or similar for their Ukrainian position (details can be found here).

While pointlessly denying any attacks on civilians and still pushing the narrative about the pseudo ‘republics’, Russia can no longer pretend it is not directly and pivotally involved in the conflict, with that including the huge numbers of enforced disappearances or abductions.