Human rights in Ukraine – 2006. XXII. The rights of refugees and asylum seekers

1. Overview

The annual reports Human Rights in Ukraine for both 2004 and 2005 pointed out that refugees and asylum seekers are among the most marginalized groups in Ukraine whose rights are most often violated. Unfortunately, no positive changes in this situation can be reported in 2006. Overall one can even speak of an increase in violations of refugees’ and asylum seekers’ rights.

Traditional routes controlled by an international mafia for illegal migrants, mainly from African and Asian countries heading towards Western Europe pass through Ukraine’s territory. The expansion of the European Union up to Ukraine’s border makes it the first country for international migration. Although Ukraine has traditionally always been a source country for migrants, its position as the “gate” between Europe and Asia, combined with its long, often unmarked borders and poor border control makes it increasingly attractive for people trying to illegally get to the EU.

Ukraine is presently experiencing pressure both on its eastern and western borders. The number of migrants and asylum-seekers trying to reach the EU from the East is rising. At the same time, ever more migrants and unsuccessful asylum-seekers are being returned to Ukraine from Poland, Slovakia and Hungary in accordance with bilateral readmission agreements. At the EU-Ukraine Summit in Helsinki on 27 October 2006 the completion was announced of negotiations on a Readmission Agreement between Ukraine and the EU. The entry into force of this Agreement has presently been delayed, however according to the agreed version Ukraine commits itself to readmit all illegal migrants which entered an EU country via Ukrainian territory. Given the lack of a fair system in Ukraine for granting refugee status, the enforcement of the readmission agreement will present a real danger that the fundamental principle of non-refoulement of asylum seekers returned to Ukraine under the readmission agreement may be violated. In parallel to this, Ukraine also signed a readmission agreement with Russia.

In the report prepared by the prominent human rights organization Human Rights Watch “Ukraine: On the Margins Rights Violations against Migrants and Asylum Seekers at the New Eastern Border of the European Union” ”[2], the Ukrainian authorities are sharply criticized for serious violations of the rights of asylum seekers and refugees; ill-treatment; the lack of fair procedure for designating refugee status; no legislative regulation for the status of asylum-seekers; corruption over granting refugee status; cases involving racism and discrimination against refugees, etc.

Despite difficulties and the extremely high likelihood that refugees’ rights will be violated, Ukraine continues to attract organizers of illegal migration. Reasons for this include shortcomings in migration legislation and endemic corruption among law enforcement officers, public officials and border guards.

According to official statistics from the Ukrainian migration service, 1,959 applications for refugee status were received in 2006 from 2,075 people (the figures are explained by the law including underage members of the family in an adult’s application). Only 55 applications were granted (according to unofficial data, the overall number of people who received refugee status, together with their children, came to 65). Among asylum seekers who received refugee status there were: 17 people from Afghanistan, 6 from Kazakhstan, 5 Iraqis, 4 Russian nationals (three being ethnic Chechens), 4 Uzbeks and 2 Belarusians. The overwhelming majority of asylum seekers were turned down at various stages of the review of their applications. For example, approximately one in ten did not even have his or her application for refugee status accepted while migration service offices refused to process the applications for refugee status of 57 percent of asylum seekers[3]. The rest were turned down after completion of official procedure at the level of the State Committee on Nationalities and Migration. Although the number of people granted refugee status in 2006 was up 30 percent on the figure for 2005 when 37 people received refugee status, in our opinion these statistics nonetheless reflect the unwillingness of the migration service to give objective consideration to asylum applications. They clearly demonstrate an intention to not grant refugee status to asylum seekers even where there are the grounds set down in international law.

At the beginning of 2006 the Vinnytsa regional migration service refused to process the applications for refugee status of two asylum seekers from Uzbekistan A. and B. The latter had left their country due to well-founded fears that they would face persecution over their participation in the crushing of a peaceful demonstration in Andijon on 13 May 2005 during which hundreds were killed. This decision was appealed in court and revoked as unlawful however that ruling from the first instance was later quashed by the Appeal Court. By March 2007 a final decision on the two applications had not been taken. It is indicative that in refusing to process documents for refugee status, the Vinnytsa regional migration service pointed to the fact that the two applicants had arrived on Ukrainian territory from the Russian Federation which they deemed to be a safe third country. This is despite the fact that even according to Ukraine’s Law on Refugees having been in a safe third country does not constitute grounds for refusing to initiate the application procedure for refugee status.

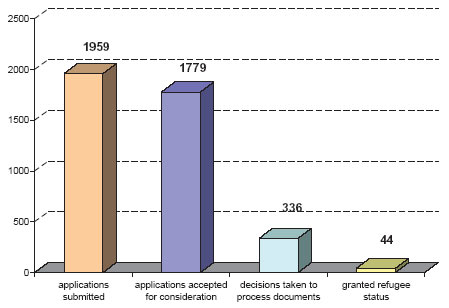

Overall in 2006 (as of 1 January 2007) the statistics for asylum applications were as follows:

applications submitted 1959

applications accepted for consideration 1779

applications not accepted for consideration 180

decisions taken to process the application 336

refusal to process the application 1237

refugee status granted 44

applications for refugee status turned down 488

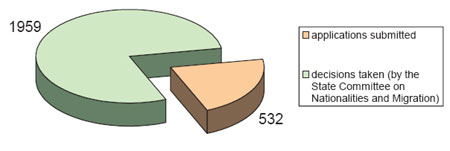

Results of the application procedure for refugee status in Ukraine in 2006 (as of 1.01.2007)

Results of the application procedure for refugee status in Ukraine in 2006 (as of 1.01.2007)

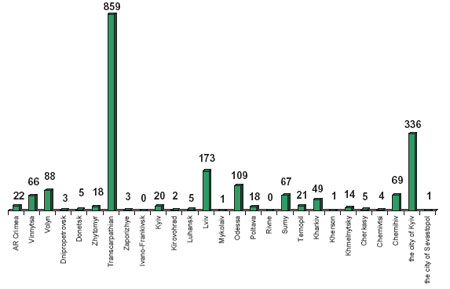

The number of applications for refugee status in Ukraine in 2006 by region, as of 1.01.2007 (in total 1959)

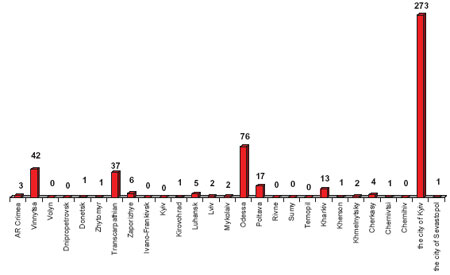

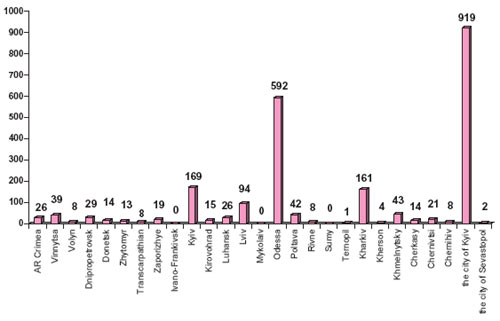

Application for refugee status turned down in 2006 by region, as of 1.01.2007 (according to figures from the State migration service – in total 488)

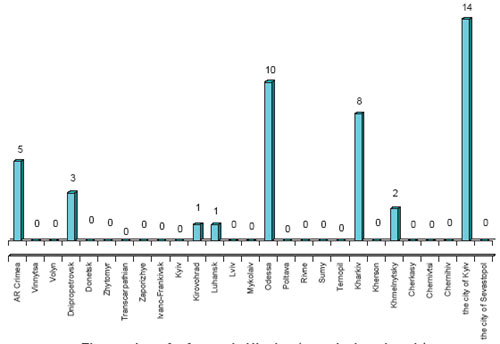

Granted refugee status in 2006 by region, as of 1.01.2007 (according to figures from the State Migration Service – in total 44)

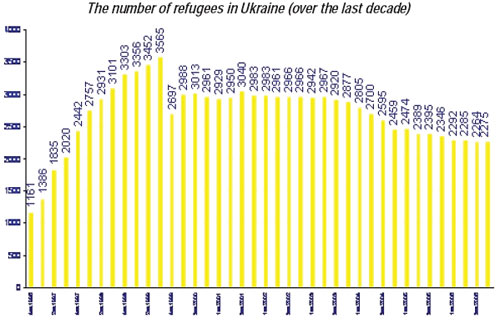

The number of refugees in Ukraine (over the last decade)

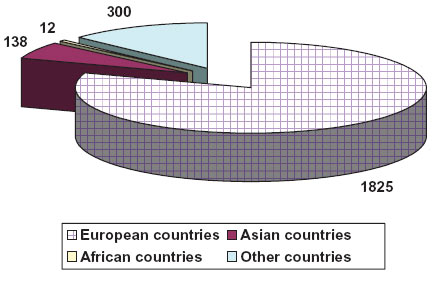

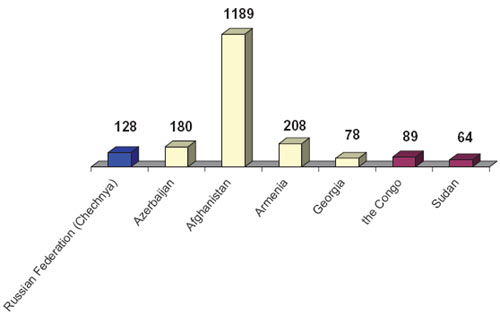

Refugee status applicants according to country of origin as of 1.01.2007

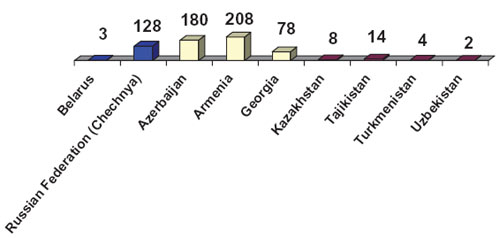

Refugee status applicants by regions as of 1.01.2007

Country of origin of the majority of refugee status applicants as of 1.01.2007

Refugee status applicants from CIS countries as of 1.01.2007

2006 saw yet another year of unsystematic and incomprehensible “reform” of the State Migration Service. During the entire year attempts continued to either place the migration service under the management of the Ministry of Justice or the control of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA), or to separate it entirely and raise it to the level of a ministry.

Despite its duty by law to defend the rights of refugees and asylum seekers, the State Committee on Nationalities and Migration, headed in 2006 by Serhiy Rudyk, effectively turned into an outpost of the battle against refugees. It can be said that as yet there has been no success in creating a just system for determining refugee status in Ukraine and the migration service headed by the central specially empowered State Committee on Nationalities and Migration is not able to efficiently and fairly consider applications from asylum seekers.

Throughout 2006, rather than carry out their official duties, the highest public officials of the State Committee on Nationalities and Migration occupied themselves with mutual recriminations and cheap intrigues. The management of the State Committee also publicly demonstrated arrogance, contempt and a discriminatory attitude towards refugees and asylum seekers.

| From an open letter by the Deputy Head of the State Committee on Nationalities and Migration of Ukraine Viktor Voronin to the SBU [Security Service], the MIA and Prosecutor General[4]: «The vast majority of asylum seekers come from regions which are dangerous from the point of view of terrorist activities or drug trafficking. These include Afghanistan, Iraq, Chechnya, Tajikistan, Nigeria, Palestine, Sierra-Leone, and so forth. There are among them, albeit an absolute minority, members of international terrorist organizations and of drug cartels, which the law enforcement agencies are aware of. … One can only guess at what such people may be up to during the extra months granted them by the State Committee on Nationalities and Migration – plans to destroy the Kyiv reservoir, a bacteriological attack, bombing the embassies of the US or European countries, seizure of hostages in Russia, arranging drug trafficking with heroin to the EU or its sale in Ukraine.”. I am alleging falsification by officials of documents and refugee files. What is behind this, is it Mr Rudyk’s general lack of professionalism? I am not making a statement as to whether there really are corrupt motives – his or another Committee member’s, that’s a matter for the investigation department. I would merely stress that such falsifications are simply impossible without the knowledge of the higher management of the State Committee on Nationalities and Migration. Why have I spoken out now? That’s very simple: on Thursday I signed a report on those cases I was aware of – no response. On Friday I wrote a second such report and said that there was a great risk that official documentation was being falsified. There was no reaction. I am left with no other option but to approach the law enforcement agencies. |

It is telling that, in spite of the public promise by the then Minister of Justice Serhiy Holovaty to investigate cases which Voronin alleged in May 2006 of falsification by employees of the State Committee on Nationalities and Migration of asylum seekers’ cases, the public were never told of the results of such an investigation.

Just at the end of 2006 there was another reform of the migration service which resulted, finally, in each Ukrainian region receiving its own subdivision. However the staff of the regional offices of the migration service is made up largely of former officers of law enforcement agencies who have a biased attitude to asylum seekers, seeing them as a threat to Ukrainian society. There is no system for regular professional development of the staff of regional migration services.

On 8 November 2006 Cabinet of Ministers Resolution No. 1575 reorganized the State Committee on Nationalities and Migration into the State Committee of Ukraine on Nationalities and Religion. Most of the management of the former State Committee on Nationalities and Migration were dismissed, and H.D. Popov became the acting Head of the newly formed Committee.

At present steps towards reforming the Ukrainian migration service remain unclear.

2. Legislative regulation

In the annual human rights organizations’ report “Human Rights in Ukraine – 2005”[5], a detailed analysis was given of legal regulation for safeguarding the rights of refugees and asylum seekers, and the problems arising in relation to this. No significant changes were made during 2006 to the legislation regulating the status of refugees and asylum seekers.

There are a considerable number of contradictory legislative acts of different levels in Ukraine which regulate the legal status of foreigners, including the status of asylum seekers. Some of this legislation, in particular subordinate legislation, for example some Orders, Instructions or Resolutions of Ministry of Internal Affairs agencies, the State Border Guard Service and the migration service, runs counter not only to the Constitution and laws of Ukraine, but to the country’s international agreements in the field of human rights. Despite such lack of compliance, these legislative acts continue to be actively applied which leads to wide-scale infringements of human rights.

Legislation on refugees in Ukraine is mainly found in the Constitution of Ukraine, international agreements to which Ukraine is a signatory and the Law of Ukraine “On refugees”.

At the constitutional level it is stipulated that “Foreigners and stateless persons may be granted asylum by the procedure established by law” (Article 26), however there is at present no Law of Ukraine “On asylum”[6]. Ukraine is a signatory to a whole range of international agreements which establish its commitments as far as protecting the rights of refugees and asylum seekers are concerned, in particular the : UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees of 1951, which Ukraine ratified in 2002, and the 1967 Protocol to this Convention..

. Regulation of the procedure for the granting, loss or withdrawal of refugee status, as well as legal and social guarantees for refugees and asylum seekers are set out in provisions of the Law of Ukraine “On refugees”. The first version of this Law was adopted by the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine in 1993 after an extremely large influx of refugees from the military conflict zone in the Transdniestr region of the Republic of Moldova. The second version, adopted in 2001, with minor amendments introduced in 2005, remains in force at the present time.

An analysis of the provisions of the Law “On refugees”, together with the amendments and additions introduced in 2005, makes it possible to conclude that the law does on the whole comply with international standards for protecting the rights of refugees and asylum seekers. The Law does however retain many norms which hamper the provision of international protection to refugees and asylum seekers, and which at times make a just procedure for establishing refugee status impossible. The procedure for obtaining refugee status in Ukraine remains extremely complicated, involving many levels.

Laws “On asylum” and “On the fundamental principles of Ukraine’s migration policy” have still not been passed. Nor is there any systematic analysis or forecasting of migrant and asylum seeker movement, nor any organized work on gathering and analysing information concerning the countries of origin of refugees. This all leads to unjust decisions being taken to turn down applications by asylum seekers at the various stages of the procedure.

3. Specific issues regarding refugee and asylum seekers’ rights

Pursuant to Article 9 § 7 of the Law “On refugees”, migration service offices determine whether to accept applications for refugee status. A refusal to do so is possible at this stage already after a quick and cursory consideration of the application on the basis of a whole range of formalities in no way connected with whether a person really is a refugee according to the definition of the Law and the UN Convention.

A particularly serious problem remains in the failure to provide appropriate identification documents for asylum seekers at various stages of the procedure for seeking refugee status.

The Law “On refugees” defines several forms of passport-type documents which are issued to asylum seekers during the procedure for receiving refugee status. These are the so-called “identity papers” containing a photograph, basic biometric information about the person, which are issued by the bodies of the State Migration Service, confirm the identity of the applicant and are valid on the entire territory of Ukraine. However in cases where an individual is turned down at any stage of the procedure for receiving refugee status, these identity papers are immediately removed, and instead of them a person is issued with documents which are not valid as identification documents, do not contact a photograph or biometric details and do not enable a person to register at the place where s/he is living or staying.

In 2006 the State Committee on Nationalities and Migration failed to make any amendments to the notorious Order No. 20 which approved the “Temporary instruction on processing documents on the granting, loss or withdrawal of refugee status”. It is this document which contains the discriminatory form “Notification of rejection” of an application for refugee status according to which people who have had their applications turned down remain for the period established by law for making an appeal without any document or identity papers.

The State has in this way created a situation whereby people who are still in the country legally since the refusal to proceed with their refugee status application may be appealed at an administrative level or through the courts within the legal time frame, are deprived of identification papers. This subjects them on an everyday basis to cruel harassment, demands for bribes and other illegal actions by those who wield official authority over them. The lack of identity documents carrying a photograph sometimes prevents an asylum seeker from receiving legal aid (aside from an expensive lawyer) since without a passport-type document notaries cannot certify instructions or other civil – legal acts. State officials are well aware of this problem which would, moreover, be possible to resolve without changing the law. The will of the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration of Ukraine would suffice, however it is this will which is lacking since, in our view, the migration service officials at all levels, together with the MIA agencies responsible for registering citizenship and individuals, have a strong interest in maintaining the status quo, this being a situation in which refugees and asylum seekers are insecure, vulnerable and deprived of their rights.

| From an interview given by asylum seeker H. from Somalia to the Vinnytsa Human Rights Group Every morning I wait for the police to come. Sometimes they’re there already at seven o’clock. They begin sneering at my document – the document (Notification of rejection of the refugee status application) there’s no place for a photo, nor for a registration stamp. “Why haven’t you appealed to the court against being turned down?”, they ask. I say that I have a year to apply to the court and that lawyers are working on my case. “We’ve had enough of you here!” the police say and laugh. We’re taking you to court. In the Leninsky District Court in Vinnytsa our cases are normally examined by Judge Saulyak. He doesn’t even look at us. First he calls the police to his office and talks about something with them, laughs, and then we go in. He quickly reads out a protocol, I don’t understand much and the interpreter doesn’t have time to translate. The judge doesn’t even ask me if I consider myself to be guilty. He tells us all to leave. 10 minutes late they call us into his office, and the judge informs me that I am being fined 340 UAH because I am supposedly “in Ukraine illegally”. The judge says “You see, I haven’t deported you” and laughs. You can’t appeal against such a court ruling. The police tell me in the corridor that they can come to my home every day! They say “think!” I think about the harassment and degradation I suffered from the armed bandits in my country. They came and threatened me with weapons because I’m from a minority clan. They also said “WE’VE HAD ENOUGH OF YOU HERE”. Strange, but the bandits in Somalia also call themselves the “police”. |

Even having received one of the four identity documents which the law establishes should be issued to asylum seekers for the period during which their applications for refugee status are being reviewed, an asylum seeker remains vulnerable and without rights.

The papers need to be regularly renewed by the migration service with an appropriate stamp being added. In almost every region of Ukraine the local migration services demand that the asylum seekers reregister at their address with the police after each such extension of the papers. Although court rulings in both the Vinnytsa and Mykolaiv regions have found such demands to reregister with the police unlawful[7], all migration service offices stubbornly continue the practice. The amount of State duty which is payable for the registration of asylum seekers is not directly stated in any law or Decree, as a result of which in various regions of Ukraine the police demand arbitrarily imposed amounts of state duty for registration. Human rights defenders, as well as the UNHCR, have for years been pointing to this problem. It would seem however that the MIA has no intention of providing passport service offices in the regions with any guidelines on this issue.

During the procedure for granting refugee status the migration services are regularly guilty of flagrantly infringing the regulations in the Law “On refugees” with regard to child asylum seekers. This problem became especially acute in 2006. Article 12 of the said Law stipulates that “The personal interview with a child separated from his or her parents shall be conducted in the presence of the child’s lawful representative who submitted the application for refugee status on behalf of the child, a psychologist or educational worker”. In fact, however, the migration services very often ignore this crucial requirement and do not approach care and guardianship bodies asking that somebody look after child asylum seekers separated from their parents. As a result, throughout the entire refugee status procedure, these children do not have legal representatives, making the whole procedure for determining their status unlawful and unjust and leading to grave violations of their rights. In 2006 the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration on repeated occasions unlawfully turned down applications for refugee status from children separated from their parents on the grounds that they had come from a safe third country, this being in direct contravention of the law. This indicates the arrogant and cynical manner in which migration officials ignore the fundament international principles on protecting refugees’ rights.

In 2006 migration service offices and mainly the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration seriously violated the Law “On refugees” in not adhering to time limits established for review of asylum seekers’ applications and for giving a final decision as to whether to grant refugee status

As of 15 June 2006, in contravention of the law, the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration had not taken decisions in more than 130 cases involving foreign nationals whose applications had been submitted more than three months earlier. As a result, applications were not able to receive refugee status during the legally established time frame or appeal against a refusal to grant it. This violated their right of movement, free choice of place of residence, freedom to leave Ukraine, to seek employment or take part in any other work activities on the basis and according to the rules of procedure established for citizens of Ukraine, etc.[8]

On Ukraine’s western border asylum seekers are held in the detention centre for illegal migrants in Pavshino, Transcarpathian region. This closed regime centre is maintained by the State Border Guard Service and sometimes holds up to several hundred people, both economic migrants and asylum seekers. Although formally representatives of two nongovernmental charities providing legal and humanitarian aid have access to the Centre, in practice almost all issues regarding communication between lawyers and detainees depend on the centre’s administration. The Vinnytsa Human Rights Group has on a number of occasions received complaints from people being held at Pavshino alleging that guards demand money from them and use physical force against them. Some members of the charities allowed to carry out work in the Pavshino Centre have, on the basis of confidentiality, reported witnessing degrading or other ill-treatment of detainees by servicemen, but have avoided direct conflict with the Pavshino Centre administration fearing that this could result in their being refused access to the centre.

Other complaints from Pavshino detainees received on several occasions by the Vinnytsa Human Rights Group have alleged a discriminatory attitude towards people of certain nationalities with regard to access to application procedure for refugee status. People from Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and China, for example, have asserted that on various pretexts their applications for refugee status were not accepted, and when they did succeed in passing these applications to border guard officers, they did not then reach the Transcarpathian region migration service.

Migrants’ rights are quite often violated when State Border Guard bodies arbitrarily and without giving reason refuse to allow foreign nationals onto Ukrainian territory. According to official statistics, in 2006 the State Border Guard refused entry into Ukraine of 18,173 people whom they deemed “potentially illegal migrants”. Who are these people and who decides to classify them as “potentially illegal migrants”? How many of them are potential asylum seekers and how many of these are then returned to their country of origin with further violation of their rights? There is no official response to such questions.

The problem remains extremely serious of forced return (expulsion or deportation) of asylum seekers to their country of origin, with these effectively not being regulated by Ukrainian legislation. Extradition in Ukraine takes place without mandatory use of a court mechanism. Although even the possibility of judicial control over the justice and lawfulness of deportation remains extremely dubious since legislation does not stipulate the mandatory participation of lawyers in the extradition procedure.

Asylum seekers and refugees have also been deported which is a violation of Ukraine’s international human rights commitments. At the point at which an asylum seeker has his/her legally envisaged official document removed [i.e. after the application has been turned down, yet while the person still has the right of appeal – translator], s/he automatically ends up in the same position as an illegal immigrant, and is often subjected to administrative deportation which may be against their will. With regard to deportation, on 1 September 2005 the Code of Administrative Justice of Ukraine came into force, and together with it, some amendments and additions were introduced to laws regulating the procedure for expelling aliens from Ukraine. Nevertheless the current administrative procedure for expulsion remains confused and places human rights in jeopardy.

The Code of Administrative Justice does not, for example, establish the periods in which expulsion takes place after a ruling is issued, does not make the presence of a defence lawyer (representative) obligatory, does not explicitly prohibit the sanctioning of extradition during court proceedings behind closed doors, and there are also no procedural guarantees for individuals who are awaiting enforcement of an expulsion order or a court review of an appeal against expulsion.

4. Court defence of asylum seekers and refugees

Decisions by regional migration services which can be contested in court fall into three main groups:

1. An appeal against the refusal to accept an application for refugee status. The grounds for such a refusal are set out in Article 12 of the Law “On refugees”., namely if the applicant is concealing his or her true identity, if s/he has previously been refused refugee status in the absence of the conditions foreseen by Article 1 § 2 of the Law and if these conditions have not changed.

2. Appeals against a refusal to process application documents for refugee status. The grounds are set out in the same Article 12: “ Decisions on refusal to process documents for resolving the issue of granting refugee status shall be made in relation to applications which is manifestly unfounded, i.e. when in relation to the applicant no conditions stipulated in paragraph 2 of article 1 of this Law exist, and when applications are associated with abuse, i.e. when applicant pretends to be some other person, and in relation to applications submitted by persons who were denied refugee status due to absence of conditions stipulated in paragraph 2 of article 1 of this Law, if such conditions did not change”.

3. An appeal against other unlawful actions or inaction during the procedure for seeking refugee status.

The following decisions of the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration can be appealed according to legally established procedure:

1. Where appeals against the refusal to accept an application for refugee status have been rejected;

2. Where appeals against the refusal to process an application for refugee status;

3. Against the granting, loss or withdrawal of refugee status.

The rules of procedure for court appeals against decisions issued by regional migration services or the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration are established by the Code of Administrative Justice which came into effect on 1 September 2005. Article 17 of the Code states that administrative courts shall have the jurisdiction to decide on disputes between individuals or legal entities and the authorities appealing against the decisions of the latter (normative legal acts or legal acts of individual force), actions or inaction.

For example, a decision by the Lutsk City District Court from 04.05.2006 failed to consider an appeal against the Volyn Regional migration service for having refused to process a refugee status application. The court, in issuing the ruling, referred to Article 16 of the Law “On refugees” and asserted that the claimant had missed the seven-day deadline for appealing to the court. However the Volyn Regional Court of Appeal revoked this ruling, stating that in accordance with Article 99 of the Code of Administrative Justice an administrative claim could be submitted over the space of a year, counted from the day when the person discovered or should have found out about the infringement of his or her right.

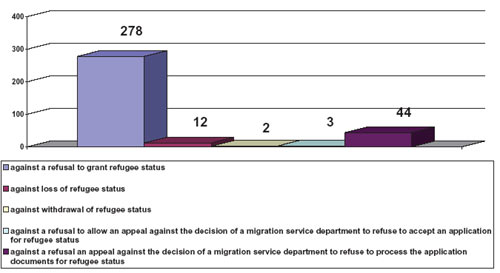

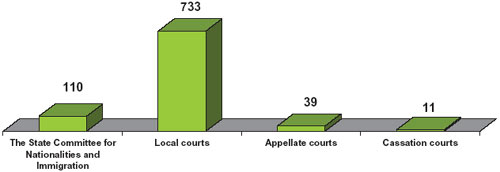

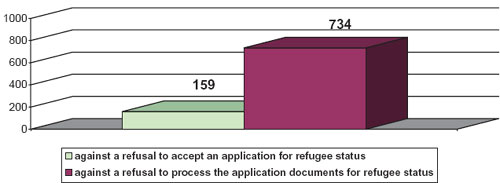

In 2006 there was an increase in the number of appeals from asylum seekers to the court defending their violated rights. Official statistics from the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration give the following statistics:

Appeals against decisions by the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration in 2006, as of 1.01.2007

Appeals against decisions by migration service departments in 2006, as of 1.01.2007

Appeals against decisions by migration service departments in 2006, as of 1.01.2007

At present, since district administrative courts have not begun functioning, asylum seekers’ first instance court cases are examined by local courts of general jurisdiction. At the end of 2006, the UNHCR, in cooperation with the High Administrative Court of Ukraine, ran the first training seminar for judges of local and appellate courts on court defence of refugees’ rights.

Courts are often uneven in their application of the procedural norms of the Code of Administrative Justice in determining jurisdiction of administrative suits against the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration. For example, Judge Korol from the Leninsky District Court in Vinnytsa twice unlawfully refused to consider administrative suits brought by asylum seekers according to where they were staying and suggested that they approach the district administrative court whose jurisdiction covers Kyiv. These rulings by Judge Korol were revoked by the Vinnytsa Regional Court of Appeal which did not prevent Judge Korol from issuing another such judgment at the beginning of 2007.

In July 2006 the Leninsky District Court in Vinnytsa (under Judge T. Salo) refused to allow a submission from the Head of the Vinnytsa Regional Department of the MIA to remand in custody Uzbek national M., who was wanted by the Uzbekistan authorities for his alleged part in the “Andijon events”. The court based its decision on the fact that M. was in the process of applying for refugee status in Ukraine[9].

In autumn 2006 the Voznesensky City District Court for the Mykolaiv region allowed an administrative suit lodged by an asylum seeker from Pakistan Y. against the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration. The refusal to grant the person refugee status was declared unlawful and revoked, and the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration was ordered to pass a decision granting Y. refugee status.[10].

Although the court decision was not appealed by the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration and it entered into force, the administrative respondent refused to enforce the court ruling with regarding to granting refugee status. It proposed instead “to reconsider Y’s application for refugee status in Ukraine”. Later, despite the fact that the State Bailiffs’ Service had launched writ proceedings over the court’s decision, the Kherson Regional Prosecutor approached the Mykolaiv Regional Appeal Court with an appeal on behalf of the State against the Voznesensky Court. The arguments presented are so representative of the attitude of the prosecutor’s office to human rights and the independence of the courts that they warrant being quoted in full.

„By ordering the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration to grant refuges status, the court infringed Article 162 of the Code of Administrative Justice of Ukraine which does not authorize the court to demand that the respondent take certain decisions which are solely within the latter’s competence.

The representation by the prosecutor’s office in the given case has been prompted to lodge an appeal by the need to defend the interests of the State, the right of which to voluntarily take decisions on granted refugee status will be violated should the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration adhere to the decision of the Voznesensky City District Court for the Mykolaiv region with regard to granting X refugee status”.

5. The illegal deportation of Uzbek refugees[11]

In February 2006 Ukraine defiantly violated its international human rights commitments by unlawfully and forcibly returning 11 asylum seekers to Uzbekistan.

Nine of the eleven had between 1 and 6 February 2006 officially applied to the migration service in the Crimea for refugee status and they had been issued with the appropriate documents confirming that they were on Ukrainian territory legally.

Yet only a few days after their applications for refugee status were lodged, on 7 February all the asylum seekers were detained in the course of a special operation by the Central Department of the Crimean SBU. They were held in an MIA centre for the reception and distribution of vagrants in the Crimea without access to legal assistance. After being detained, the other two Uzbek nationals also applied for refugee status.

On 13 February all of the 11 men were handed “Notification of the refusal to process their applications for refugee status”. By 14 February they had been secretly taken to the Kyvsky District Court in Simferopol which ruled that all 11 be deported since they did not have legal grounds for being in Ukraine. The grounds for the arrest of the Uzbeks remain unclear as does the reason why, if this was an arrest of normal illegal immigrants as the law enforcement agencies tried to suggest, the Central Department of the SBU had been involved. The detained men allegedly gave written consent to being returned to Uzbekistan and a rejection in writing of their right of appeal against the court ruling. In fact, however, such written rejections are unlawful given that they contravene the Constitution and relevant procedural legislation.

They were taken by plane from Simferopol to Tashkent during the night between 14 and 15 February.

As we can see, the detention and deportation of the Uzbeks was carried out with numerous flagrant violations of Ukrainian legislation. The worst aspect is that these people really did face danger in Uzbekistan, and sending people to an unsafe country is a direct violation of Ukraine’s international commitments under the UN Convention on the Status of Refugees, the UN Convention against Torture and Cruel Treatment and the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms..

Soon after the deportation, all the Uzbek nationals were arrested and most were sentenced to between 3 and 13 years imprisonment during court trials which did not meet international standards for just court proceedings. According to human rights organizations the Uzbek asylum seekers were subjected to torture and ill-treatment in their country of origin.

None of the attempts to justify their actions given by state bodies stand up to criticism.

| Public statement from Ukrainian civic organizations on the extradition of Uzbek asylum seekers

The extradition of the asylum seekers to Uzbekistan was a demonstration of flagrant disregard for international standards of the protection of refugees. The asylum seekers were deprived of legal assistance, access to employees of the UNHCR, and to any procedure in keeping with the standards of a just legal system. Such actions by the authorities testify to a cynical lack of respect for fundamental human rights, international commitments and also national law. The government of the country which our regime handed those people over to has gained notoriety throughout the world through its use of concentration camps, the large number of political prisoners against whom the state applies torture, extra-judicial executions and the death penalty. The government of Uzbekistan is also know for its practice of brutally crushing any manifestations of free thinking, freedom of expression, freedom of religion and freedom of peaceful assemblies. The haste with which the Ukrainian authorities handed the refugees over to the Republic of Uzbekistan is not only a demonstration of political double standards in the field of human rights, but also shows the lack of humanity and simple sound judgement in taking decisions about people’s lives. The way in which the authorities behaved denigrates Ukraine to the level of countries for whose governments the value of human life is an empty phrase. Moreover, the information we presently have suggests that the extradition of the Uzbek asylum seekers was a planned special operation by the Security Service of Ukraine, the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration of Ukraine, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and some other state executive bodies. We consider that the direct responsibility for this flagrant violation of human rights lies with the heads of the state bodies named. However the responsibility also lies with the President of Ukraine who did not fulfil his constitutional duty to guarantee the observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms. [12]. |

| UNHCR appalled by deportation of Uzbek asylum seekers from Ukraine “We deplore this action, which the authorities carried out in contravention of their international obligations", said Pirkko Kourula, Director of UNHCR’s Bureau for Europe. UNHCR is seeking urgent clarification from the Ukrainian authorities and seeking additional information about the fate of the deportees. On Wednesday afternoon, UNHCR learned from media reports that the detained Uzbeks had been deported during the night of 14-15 February. The 11 men are now presumably in the custody of the Uzbek authorities. Details of the situation are still emerging. On 7 February, UNHCR learned that 11 Uzbek asylum seekers had been arrested in two different locations in Crimea by unidentified Ukrainian law-enforcement authorities. The Ukrainian authorities confirmed the asylum seekers had been taken to a detention facility in Simferopol after the authorities received requests for their extradition from the Prosecutor’s Office of Uzbekistan, alleging involvement in the civilian protests in Andijan on 13 May 2005, which ended violently. As early as Tuesday, 7 February, and again on 14 February, UNHCR wrote to the Ukrainian authorities requesting official guarantees that no asylum-seeker would be forcibly returned unless they had been determined not to be a refugee, after going through full and fair asylum procedures, including the right to appeal. UNHCR also requested access to the detained Uzbeks. Being the subject of an extradition request does not remove an asylum seeker or refugee from international refugee protection. UNHCR reiterates the importance of the principle of non-refoulement, under which no refugee or asylum seeker whose case has not yet been properly assessed, can be forcibly returned to their country of origin. Refoulement is a violation of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, to which Ukraine is a signatory, and is also contrary to international customary law. It is also a breach of the UN Convention against Torture to send persons back to countries where they may face torture. Refoulement is also specifically prohibited under Ukrainian national law. UNHCR is seeking assurances from Ukraine that in the future, asylum-seekers from any country will be treated in full respect of Ukraine’s international and national legal obligations concerning refugees and asylum seekers.[13]. |

Only in May 2006 under pressure from the international community did the Ministry of Justice recognize that there had been an infringement of human rights in the deportation of the Uzbek asylum seekers.[14].

However other State bodies – the Ministry of Foreign Affairs[15], the SBU[16], the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the State Committee for Nationalities and Immigration[17], have continued in the worst traditions of Soviet propaganda to defend their actions, and those responsible for the shameful deportation of the Uzbek asylum seekers have not been punished.

It is also interesting that the SBU began trying to justify its actions by claiming that the 11 Uzbeks had been involved in terrorist activity. Besides the fact that such assertions were not backed by any evidence, they also clashed with the overall statistics for the year. For example, at the beginning of 2007 SBU spokesperson M. Ostapenko stated that during 2006 only two foreign nationals had been deported in connection with terrorist activities[18]. The given explanation by the SBU for the deportation of the Uzbeks is thus contradicted and is clearly untrue.

6. Conclusions and recommendations

With regard to the recommendations from human rights organizations for improving the system for protecting refugees’ and asylum seekers’ rights published in last year’s report, the authorities only took into consideration a few of them. All those recommendations not heeded remain, in our opinion, valid for 2007.

Since Ukraine is failing to carry out its basic commitments regarding the protection of the rights of refugees, despite its having signed and ratified the UN Convention on the Status of Refugees and the Protocol to it, we consider that the migration bodies of State Parties to this Convention should not recognize Ukraine as a “safe country” for returning refugees and asylum seekers.

.

[1] Prepared by the Coordinator of the Vinnytsa Human Rights Group Dmytro Groisman.

[2] Available on the Human Rights Watch site: http://hrw.org/reports/2005/ukraine1105.

[3] Migration service bodies are empowered to i) accept applications for refugee status; ii) decide whether to process applications for refugee status and iii) consider whether refugee status should be granted. (The Law on Refugees, Article 7, p. 1, 4 and 5) The difference between the first two stages can seem somewhat elusive. Following an interview with an applicant, the application can be “accepted” however then, (theoretically following closer scrutiny) the migration service body can decide to refuse to process the documents. It is only after the first two stages have been passed, that the third commences, namely the review of a person’s case with a decision to grant or refuse to grant asylum. (translator)

[4] See : http://proua.com/speech/2006/05/30/164027.html http://unian.net/ukr/news/news-156007.html

[5] The Report is available on the sites: www.helsinki.org.ua and www.khpg.org.ua

[6] The meaning here of the Ukrainian притулок – prytulok, is probably rather broader than the modern use of the word “asylum”., encompassing the general understanding of refuge, a place to stay. Presumably, what would be included in such a law would be provisions for people who may not receive refugee status, but cannot, for example, be sent back to a country with the death penalty, etc. I have avoided in many places using the customary English “apply for asylum” in order to retain the distinction drawn by the author. (translator)

[7] See the Decision of the Leninsky District Court in Vinnytsa in the administrative jurisdiction case №2а-335-06 from 8 June 2006 and the Decision of the Mykolaiv region Voznesensky City District Court in the administrative jurisdiction case №2а-126-06 from 12 July 2006

[8] From an Instruction of the Deputy Prosecutor General of Ukraine T.K. Kornyakova to the Head of the State Department for National Minorities and Migration S. Rudyk from 29 June 2006 №07-НН-212

[9] Decision of the Leninsky District Court in Vinnytsa from 17 July 2006

[10] Decision of the Mykolaiv region Voznesensky City District Court in the administrative jurisdiction case №2а-126-06 from 26.09.2006

[11] More information about this case can be found in the article “Only you are unfailing, betrayal …” by Yevhen Zakharov http://khpg.org/en/1142020420 and many other articles on the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group website

See also the OSCE Human Dimension Conference in October 2006 and material from the International “Memorial” Society “Refugees from Uzbekistan in CIS countries”: : http://osce.org/conferences/hdim_2006.html?page=documents&session_id=62 (http://osce.org/item/21559.html?lc=RU).

[12] Public statement from Ukrainian civic organizations on the extradition of Uzbek asylum seekers – the statement in full can be found at: http://khpg.org/en/1140540016

[13] Official statement from the UNHCRО on 16 February 2006 http://unhcr.org.ua/news.php?in=1&news_id=77&lang=e

[14] See Letter № Б-8320-18 from the Deputy Minister of Justice D. Kotlyar from 3 May 2006 // http://khpg.org/en/1147114502 .

[15] See the statement from the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the annual OSCE Human Dimensions Conference in Warsaw (October 2006) (http://helsinki.org.ua/files/docs/1160824378.pdf) and UHHRU’s response (http://osce.org/documents/html/pdftohtml/21313_en.pdf.html).

[16] See, for example, SBU letter from 26 August 2006 року № 5/2/2-15648 // http://community.livejournal.com/uzbek2006/22004.html#cutid1.

[17] See, for example, Letter from the State Committee for National Minorities and Immigration to Amnesty International, dated 25 December 2006 № 7/3-18-1384 // http://community.livejournal.com/uzbek2006/28917.html#cutid1.

[18] There are no terrorists in Ukraine! // MIGnews.com.ua: http://mignews.com.ua/categ186/articles/246402.html.