Russian court overrules historical facts in show trial of two Ukrainians

From left Stanislav Klykh, Mykola Karpyuk

From left Stanislav Klykh, Mykola Karpyuk

Where the facts do not coincide with the Russian investigators’ charges against two Ukrainians on trial in Chechnya, it is the facts that are discarded. Quite literally, since the court has refused to include evidence from the Memorial Human Rights Centre which demonstrate that most of the impugned crimes never happened. The analyses do, however, demonstrate that most of the impugned crimes never happened, and therefore suggest that the men’s lurid confessions were obtained through torture.

Hearings scheduled for March 14 and 15 were adjourned after family members arrived in Russia, almost certainly with compelling evidence that neither 53-year-old Mykola Karpyuk nor 41-year-old Stanislav Klykh was in Chechnya at the time Russia is alleging. The postponement is apparently due to the illness of presiding judge Vakhit Ismailov. Klykh’s 72-year-old mother and his cousin, as well as Karpyuk’s brothers had come specially, together with Maria Tomak, coordinator of the Let My People Go campaign. For both families, the journey was a major expense.

Klykh’s lawyer Marina Dubrovina has also expressed concern about medication which has been administered to Klykh since the middle of February, as well as injections given against his will. The prison doctors claim that the drugs are against a cold, however Klykh’s lawyer says that his behaviour has changed since taking them and he has become passive and removed. Klykh has repeatedly alleged torture and said that he was given psychotropic drugs during the 10 months when Russia held him incommunicado, so this new use of unidentified medication is of great concern. Dubrovina has now lodged a formal demand for information about the drugs given..

His behaviour from the beginning of the trial and certainly in January appeared extremely disturbed, even psychotic (details here). An examination was ordered, however this was provided by Russian medical staff who found nothing wrong. It was even suggested that Klykh could be charged in addition with ‘contempt of court’. There is urgent need for an assessment by independent doctors.

Karpyuk and Klykh are accused of having taken part in fighting in Chechnya 20 years ago and having killed a number of Russian soldiers during battles in Dec 1994 and Jan 1995. Karpyuk was the deputy leader of Right Sector and had been in the nationalist movement UNA-UNSO. He was effectively abducted in March 2014, and for a long time it was feared that he had been killed. Klykh appears to have been arrested while on a trip to Russia in order to provide another Ukrainian defendant. Although the history lecturer from Kyiv was once fleetingly in UNA-UNSO, he had long left it and at the time in question was concerned only with passing his university exams in Kyiv, not killing Russian soldiers in Chechnya.

The case is based solely on the ‘confessions’ of the two defendants and one other person held in a Russian prison. Klykh was held incommunicado, without access to a lawyer, for 10 months; Karpyuk for 18 months. Both men retracted all confessions as soon as they received a lawyer. They have given consistent accounts of the torture applied, and both have lodged applications with the European Court of Human Rights over their treatment.

The one small achievement in this case is that the court was forced to agree to trial by jury. This, however, may be of limited use since the judge – Vakhit Ismailov – constantly refuses to add evidence demonstrating the men’s innocence to the case. This includes ample evidence from Ukraine that the men had never set foot in Chechnya.

In a statement from Feb 17, 2016, Memorial HRC declared both men political prisoners. It pointed out that its four-part analysis had demonstrated that the indictment contains fictitious crimes, a huge number of factual mistakes and is almost totally based on testimony which the men have retracted. It notes that some of the lurid confessions are to heinous crimes which simply never happened. The prosecution has left the confessions in the indictment, but not charged the men. Memorial believes that this is so that monstrous details of non-existent crimes can have an emotional impact on the jury which the defence will be powerless to fight.

The confessions provided by Oleksandr Malofeyev, a Ukrainian national settled in Russia, cannot be regarded as any more reliable. Malofeyev was already serving a 23-year sentence in a Russian prison. As an HIV positive drug addict with hepatitis B, C and tuberculosis, it would be easy to put pressure on him by threatening to withdraw his treatment.

The trial is now taking place without either of the two defendants. Karpyuk was removed at one of the first hearings in October 2015 for his open contempt of the proceedings, Klykh on Feb 8 this year.

At the previous hearing on March 9, Alexander Cherkasov, head of the Memorial HRC Council, gave evidence as witness for the defence.

His testimony was vital since it concerned the actual facts around the storming of Grozny by federal forces during the winter of 1994-95, the deaths of Russian soldiers and the allegations of torture against POWs. Cherkasov himself was involved at the time of the first war in Chechnya with searching for people who were missing and in building a database of information. Many of the questions which the defence put were, however, rejected by the judge.

The testimony certainly unravels the prosecution’s case since they place in doubt the historical accuracy of Malofeyev’s account of battles. At the time in question, it appears that there were no Russian units near Minutka Square, as alleged. Malofeyev claimed also that Ukrainian fighters had tortured captured Russian soldiers in a particular street in February 1995. At that time the place he mentioned was far into the rear of the Russian forces. Citing information received at the time, Cherkasov was able to say that there was nothing that would confirm the tales of torture and extrajudicial executions presented by the prosecution. He pointed out also that the investigators had not provided any information as to bodies found with marks of torture, or of the identity of the victims.

Of the 30 Russian soldiers whom Russia is claiming Karpyuk and Klykh killed, 18 died in another place altogether, and a further eleven were not killed by gunfire, as the prosecution claims.

The judge interrupted Cherkasov a number of times, claiming that he was not answering the questions but leading them on “journeys through history”.

The history in question proves the men’s innocence. This was most likely why Judge Ismailov rejected the application to include Memorial HRC’s four-part analysis to the case material.

More details about the Memorial analysis here:

Tortured for the Wrong Confessions: Russia’s ‘Ukrainian Nationalist’ Charges Demolished

Memorial exposes Russia’s cynical con in trial of ‘Ukrainian nationalists’

Russia’s ’Ukrainian Nationalist’ Show Trial: No Bodies, No Proof, but Good ’Confessions’

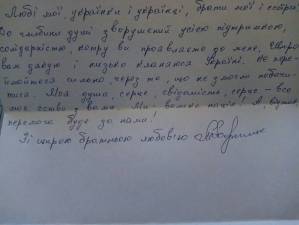

Mykola Karpyuk was able to pass a letter out addressed to his brothers and to Ukrainians. He writes how deeply moved he has been by the solidarity and support shown and sends greetings to Ukraine. Do not be too upset that they were not allowed to meet, he says, since with his heart, soul, his very being he is with them. “We are a great nation, and therefore victory will be ours”, he writes.

Please write to the men - even a single sentence or two will send an important message both to them, and to the Russian authorities, that they are not forgotten.

The addresses: Mykola Karpyuk (in Russian Nikolai)

364037, г. Грозный, Ленинский р-он, ул. Кунта-Хаджи Кишиева, 2. Следственный изолятор №1, Карпюку, Николаю (1964)

Stanislav Klykh

364037, г. Грозный, Ленинский р-он, ул. Кунта-Хаджи Кишиева, 2. Следственный изолятор №1, Клыху, Станиславу (1974)

Or send your letters to post.rozuznik[at]gmail.com, a civic initiative helping to get mail to Russian-held political prisoners They will deal with writing the envelope and sending it on. .

If you are unable to write in Russian, the following would be quite sufficient:

Желаем здоровья, мужества и терпения, надеемся на скорое освобождение.

(we wish you good health, courage and patience and hope that you will soon be released).