Survey finds only 18% identifying with Kremlin-backed ‘Donetsk people’s republic’

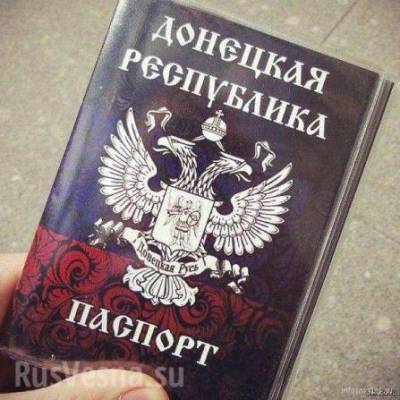

If the results of a recent survey can be trusted, less than one in five residents of areas under the control of the so-called ‘Donetsk people’s republic’ [DNR] identify themselves as ‘citizens’ of this unrecognized creation. The result is even lower than the level of support which the militants themselves inadvertently revealed, and then ‘adjusted’, but it can certainly not be dismissed as insignificant. While opinions vary about whether any sociological survey under present conditions can provide a reliable result, there is general agreement that time is likely to increase the divide between residents of the area and the rest of Donbas.

The survey was commissioned by the Committee of Voters of Ukraine [CVU] and the linked ‘Factory of Thought ‘Donbas’ Analytical Centre, under the auspices of the Kyiv office of the German IFAK Institute. 800 people were interviewed from May 30 to June 13 in areas under Ukrainian government control, and a further 600 on an anonymous basis in militant-held areas.

Sociological surveys before the conflict always pointed to the strong regional identification of people in the Donetsk oblast, and around 60% still clearly feel this, whether in the so-called ‘DNR’ or not. The latest survey confirmed shared ‘socio-cultural features’, such as the respondents’ view that a battle is going on between countries for spheres of influence in Ukraine and a battle between oligarchs for spheres of influence.

On some issues, however, there was a sharper divide. Only 9% of people in DNR would want Ukraine to join the EU, as against 23% in the non-occupied territory. 48% in DNR spoke in favour of a political and economic union with Russia as against 23% of those in areas not under militant control.

The authors of the report have issued fairly alarming warnings. They assert that Ukraine could, within 3 to 5 years, risk ‘irrevocably losing’ the people living on militant-controlled territory. Dmytro Tkachenko, head of the ‘Factory of Thought’ considers the fact that 18% identify themselves as citizens of DNR and that 28% are frightened at the thought of their territory returning under Ukrainian government control as worrying.

His colleague Yelizaveta Rekhtman points to specific reasons. In first place is the information vacuum which DNR residents are in with constant propaganda against the Ukrainian government. She believes, however, that the strict pass system crossing into and from areas under Ukrainian government control and the general rift between DNR and the rest of the country are alienating people, making them doubt the Ukrainian government’s willingness to take them back.

They stress the need to build communications with those Ukrainians remaining on militant-controlled territory. One such ‘bridge’ they view in guaranteeing the economic needs of residents, another in breaking through the information vacuum.

All of this may be true, but the reasons are extremely complex, and at least as far as the information vacuum is concerned, the militants have since the first days actively blocked any free sources of information, including Internet sites.

This also raises another issue. Even if the organizers did have their own means of quietly interviewing people without being ‘arrested’ by the Kremlin-backed militants, many respondents may still have been loath to answer honestly fearing that they might be ‘denounced’.

As mentioned, on September 11, 2015 the DNR news agency proudly reported a ‘significant increase’ in support for ‘DNR’, with the figure supposedly having risen from 22% to 29%. There was huge media attention in Ukraine, with the figure seen as indicating the lack of support for the militants. The report was later doctored to give the kind of levels which Russian surveys give President Vladimir Putin.

There is at present no effective way of judging whether any of the percentages obtained are increasing or decreasing. Certainly other analysts broadly agree with Factory of Thought in their expectation that the divide can only increase. Historian Yaroslav Hrytsak sees one of the inevitable changes as being a weakening of the tradition identification with Donbas. In Lviv, he says, surveys had always found that people identified themselves as Ukrainian. In Donbas, people saw themselves as first and foremost from the area. “Not Ukraine, not Russia, but Donetsk. People had broken away from Russia, but had not arrived in Ukraine”. Now, he adds, surveys outside areas under militant control are showing that this is changing. In the north of the Luhansk oblast, for example, people surveyed identify themselves as part of the traditional area of Ukraine which includes the Kharkiv and Sumy oblasts, while Mariupol residents are also inclined to identify themselves with Priyazovya, which includes parts of the Kherson and Zaporizhya oblasts. People are, sadly, trying in this way to distance themselves from the area of conflict, he believes.

Worth noting, given the fears expressed by people under DNR control, that a monitoring mission which visited areas in Donbas which militants had occupied for several months, before being driven out also reported that people had awaited the arrival of Ukrainian armed forces with trepidation.

“The residents of Krasny Lyman, the city liberated first on June 4 recounted how they had awaited with terror ‘purges’; arrests; repression from the Ukrainian armed forces. The ‘purge’, however, was confined to a simple viewing of flats, without even checking documents, and the first day of Sloviansk’s liberation began with free sausages being handed out. There were no reports later either of repression against the local population in liberated cities.”