Ukraine bans import of ’anti-Ukrainian’ books from Russia

Ukraine’s parliament has passed a law aimed at checking books from an aggressor state for ‘anti-Ukrainian content’ and, where such content is found, banning them. While the ongoing abundance on the Ukrainian market of material full of toxic lies and propaganda is of concern, doubts arise about the law’s efficacy, as well as over the mechanisms for achieving its stated purpose.

Draft bill №5114 introducing amendments to legislation aimed at “restricting access to the Ukrainian market of foreign printed material with anti-Ukrainian content’ was originally adopted by the Cabinet of Ministers on September 8. It was considered by the parliamentary committee on freedom of speech in November and recommended for adoption. The bill was passed in its second and final reading on Dec 8, with 237 MPs supporting it (the minimum required is 226), and unless vetoed by the President, will soon come into force.

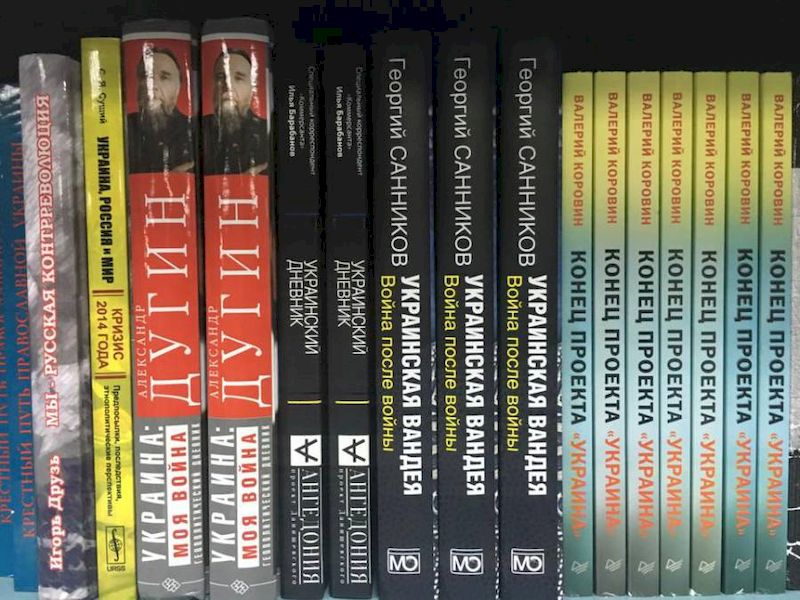

Books on sale in a central Moscow bookshop in November 2016. They include Valery Korovin’s ’End of the ’Ukraine’ project’ Alexander Dugin’s ’Ukraine: My War’ and a number of books by Kremlin-backed militants (Photos: Olga Irisova)

The bill imposes a permit system for import of printed material from an aggressor state or from Ukrainian territory currently occupied by Russia or Kremlin-backed militants. There is no restriction on individuals bringing up to 10 copies of a book into Ukraine, and the law applies exclusively to countries identified as aggressor states. At present this applies only to Russia, as per a parliamentary resolution from January 2015.

The explanatory note estimates that over 70% of printed material on sale in Ukraine comes from Russia.

There are already bans on printed material which calls for the violent overthrow of the government, incites enmity, etc. The new bill introduces a new category which seems dangerously broad, namely:

“popularisation or propaganda of an aggressor state and its executive bodies, and representatives of these bodies and their particular actions which create a positive image of the aggressor state, justify or declare as legitimate occupation of Ukrainian territory”.

Implementation of the law is to be ensured by the ‘central executive body which forms and implements state policy in the information sphere’. This is presumably the rather controversial Ministry of Information Policy created at the end of 2014. There is less clarity about the ‘expert council’ within this ‘central executive body’ which is to be responsible for assessing the printed material. The law states that this is made up of “representatives of executive bodies, branch associations, unions, the civic expert community, publishers, prominent cultural, artistic, scientific and educational figures, social psychologists, media experts and other specialists in the information sphere”.

This is a long, yet vague, list, with no information as to how and by whom the unspecified number of members will be selected and mechanisms of accountability. The law also mentions that cancellation of a permit can be challenged by the court, but does not say whether the refusal to grant a permit can be appealed.

The law states only that the ‘central executive body’ will draw up criteria for such assessment “in accordance with the requirements of this Law”.

If that is supposed to be clear, it is not. The wording of the added restriction is vague and can be interpreted as broadly as the ‘expert council’ deems fit. This alone presents opportunities for corruption.

It is also difficult to assess how far the restrictions would go. Would they cover, for example, any material that treated Crimea under Russian occupation as ‘Russian’? If in that case the material was seen to be openly justifying an armed invasion by Russian forces, and occupation recognized by the International Criminal Court as international military conflict, the situation with Donbas is less clear cut. While there is plenty of evidence of Russia’s major role in the conflict, a ban on material for treating the so-called ‘republics’ as legitimate may well be in breach of the Minsk Agreement.

With respect to Russian-produced material which, for example, lies about the military nature of the occupation of Crimea, claims that Ukraine is committing “genocide of the Russian-speaking population of Donbas” or argues that Ukraine does not really exist as an independent state, the situation may seem clearer, but only at first glance. Russia’s most virulent propaganda and warmongering are primarily effective on television and the Internet which will not be touched by this law. In fact, the books likely to be banned under the law – by Russian fascist ideologue Alexander Dugin, Sergei Glazyev, adviser to Russian President Vladimir Putin and others are all easily available on the Internet. It may be grotesque to see books on sale from people who have played direct roles in the military aggression against Ukraine, but the ban seems more symbolic, than aimed at seriously countering the lies. It would surely be more effective, and less open to accusations of censorship, to impose restrictions on books which purport to be factual, but which contain deliberate lies.

Even then, however, any such law will run up against difficulties. A recent Bloomberg interview given by Putin makes quite outrageously false assertions about Crimea and about the tragic disturbances in Odesa on May 2, 2014. The efforts spent by an expert council on finding and banning a few books would be better spent on a real information campaign aimed at ensuring that Putin’s lies do not go unchallenged.