Ukrainian police violently dispersed protesters without any court order

It is becoming increasingly clear that there was no legal justification for the dispersal of a tent camp of protesters from outside the Verkhovna Rada on 3 March and the detaining of over 100 activists. The Head of the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Secretariat also reports that the nature of the bodily injuries sustained during the dispersal suggests that the police used excessive force.

The protest camp was initially set up by supporters of Mikheil Saakashvili, the former Georgian President, then Governor of the Odesa Oblast, who turned into a fierce critic of Ukraine’s President Petro Poroshenko and was stripped of his Ukrainian citizenship in July 2017. That move and later abduction-like deportations of Saakashvili associates have aroused considerable concern in connection with clear rights violations.

Saakashvili is a controversial figure, and the protest outside the Verkhovna Rada did not have very widespread support. Disturbances on 27 February, which, according to the authorities, left 14 police officers injured, prompted even Saakashvili’s Movement of New Forces party to distance itself from the protests.

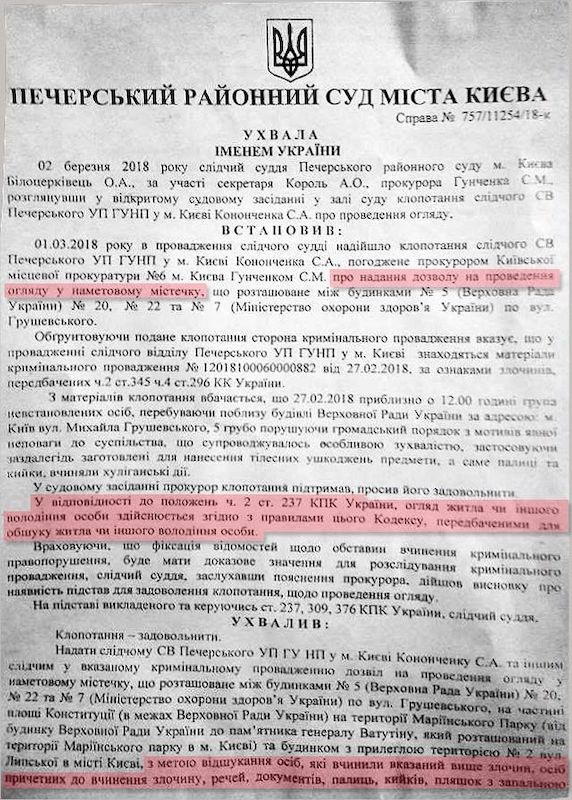

It was assumed on 3 March that the court order used to justify the operation by Ukraine’s National Police and National Guard had permitted the physical removal of the protest camp. The court warrant was made public on Tuesday by MP Mustafa Nayyem, and shows that the application filed on 2 March was for permission to carry out an inspection of the protest camp in connection with a criminal investigation launched over the disturbances on 27 February. The order issued by a judge from the Pechersky District Court on 2 March states that permission for the inspection is given in order to find the individuals believed implicated in the offence, as well as material evidence for the criminal proceedings.

Even if, as the authorities asserted, nine grenades, some Molotov cocktails, and five smoke bombs were seized, there were no legal grounds for dispersing the protest, nor for the blanket detention of activists. According to Nayyem, 111 people were detained, with only four protocols drawn up over alleged administrative offences. “Since no other proceedings have yet been initiated, it is clear that the police do not have proof of other crimes having been committed”, he asserts. It was reported on Saturday that the people held for some time in two different police stations had been detained as ‘witnesses’ though what this was supposed to mean is unclear.

As mentioned, Bohdan Kryklyvenko, Head of the Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Secretariat, also believes that excessive force was applied during the operation. Over 10 protesters had head injuries, which would suggest direct breach of Article 26 of the Law on the National Police. This norm specifically prohibits hitting people around the head as well as certain other specified parts of the body.

Lawyers are already working with people who were detained that day and will be representing them in court. Kryklyvenko calls on all those who suffered as a result of the events on 3 March to make formal complaints about the violation of their rights. He was extremely concerned by the images of four or five men being forced to kneel in the snow. He dismisses the claim made by Artem Shevchenko, police spokesperson, that the activists had been able to smoke and to make phone calls while in that position, and says that the men appear to have had their hands bound behind their back.

As reported earlier, Shevchenko also claimed that this was normal practice in a number of western countries, though did not specify which.

Kryklyvenko says that an open appeal, launched by the Ombudsperson Valeria Lutkovska, the Centre for Civil Liberties, Human Rights Information Centre has been endorsed by around 20 other rights NG0S

The appeal’s authors see strong grounds for speaking of several serious violations of human rights guaranteed by Ukraine’s Constitution. These include the right to peaceful assembly, since there had been no court order enabling the dispersal of the entire camp. The police had a duty to localize any specific individuals who were disturbing the peace, without rounding up everybody as was the case on 3 March. The prohibition on torture and ill-treatment is likely to have also been breached by the excessive force seen in a number of the injuries sustained by protesters, as well as degrading treatment, including the fact that men were forced to remain on their knees for some time. The right to liberty was also compromised by the unwarranted period of detention in the case of over 100 activists.

The violation of freedom of speech seen in the treatment of at least three journalists has already been reported here, and has elicited concern from the Committee to Protect Journalists and other international NGOs. One of the three journalists, Serhiy Nuzhnenko from Radio Svoboda ended up hospitalized with chemical burns, after an officer used pepper spray straight in his face. In all three cases, there could have been no doubt that the men were from the media, and in fact, Bohdan Kutiepov from Hromadske reported that he received worse treatment because of his press jacket.

It has since been reported that the officer involved in the attack on Nuzhnenko has been suspended pending the results of an internal investigation. It remains to be seen whether the probe this time actually moves beyond promises while media attention is focused on the event. The Ombudsperson and rights groups note that the “cynical utterances by certain officials”, with these clearly including Shevchenko, further undermine confidence in an objective investigation.

It is difficult to feel optimistic given that the law enforcement bodies themselves gave no indication that they had stepped so far beyond the court sanction received. The police also denied that any officers had been without numbers on their helmets or other means of identifying individual officers. This directly conflicts with the accounts of many witnesses.

The Ombudsperson and human rights groups demand a swift and effective investigation from the Prosecutor General’s Office and call on parliament to consider draft bills on ensuring that all police and military servicemen can be identified as soon as possible.

Given the disturbing behaviour on 3 March, they also believe it important that the Cabinet of Ministers pass normative documents on the actions of law enforcement bodies in safeguarding public order during mass events.

Whatever people’s view of Saakashvili and / or of the protest camp may be, the events on 3 March led to many comparisons with dispersals by Berkut officers during Euromaidan. Criticism, Nayyem stresses, is not about attacking the National Police, but about ensuring that post-Maidan enforcement officers truly do become ‘our police’.

The 2 March court order - highlighting by Mustafa Nayyem