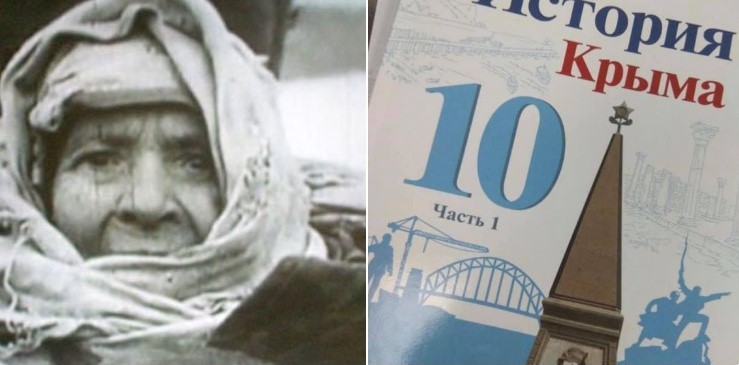

Russia repeats lies about Crimean Tatars used by Stalin to justify the Deportation in school history textbook

Scroll down to the bottom for updated information

Over 50 years after the Soviet Union formally refuted the lies about Crimean Tatars that Joseph Stalin used to justify the 1944 Deportation, Russia has reinstated them in a school history textbook. This is not just a grave distortion of history, but a move surely aimed at inciting enmity towards the main indigenous people of Crimea, the vast majority of whom opposed Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

The textbook ‘History of Crimea’ is for the 10th grade and will be used from September 2019, however it has already been delivered to some libraries in occupied Crimea. It is probably no accident that the Russian-appointed ‘minister of education’ Natalya Goncharova was on the academic editorial board for the textbook, together with prominent Crimean politicians holding high posts in the Russian occupation government (Sergei Tsekov; Grigory Ioffe, Vladimir Bobkov).

The textbook repeatedly claims that the Crimean Tatars were collaborators who helped the Nazi occupiers during the Second World War. It is asserted, for example, that “the majority of the Tatar population were loyally disposed towards the Germans and many actively helped them”.

All of this is a depressing rehash of the excuse used for the Deportation in 1944 of the entire Crimean Tatar people which is recognized by Ukraine as an act of genocide. More than 180 thousand Crimean Tatars were forcibly deported over a few days following May 18, 1944. Families were given as little as 15 minutes to prepare for the journey, with the NKVD operation carried out with enormous brutality.

While the other nationalities also deported under Stalin were allowed to return in the 1950s, the Crimean Tatars were only formally able to come back to Crimea from 1974, with this only becoming a real possibility during Mikhail Gorbachev’s ‘perestroika’, and then after Ukraine’s gained independence.

This was despite the Supreme Soviet’s decree from 5 September 1967 which called attempts to level accusations against some Crimean Tatars of collaboration at the entire Crimean Tatar population groundless and said they must be withdrawn.

With respect to accusations of collaboration, Asya Pereltsvaig writes that it is true that “many Crimean Tatar religious and political leaders had indeed called for collaboration with the Nazis, considering them as “the enemy of the enemy”” and that there were Crimean Tatars who fought for Wehrmacht battalions. The numbers, however, would constitute less than 5% of the total Crimean Tatar population. It should also be remembered how up to 80 thousand Crimean Tatars fought in the Soviet Army and took part in the partisan struggle against the Nazi and Romanian occupiers. When the NKVD arrived on 18 May 1944, they found mainly women, children and the elderly.

As far as the Wehrmacht battalions are concerned, historian Greta Lynn Uehling writes that “Crimean Tatar participation in the German battalions was not necessarily voluntary, often being secured at gunpoint. It must also be added that severe hunger and disease in the Soviet ranks led people of all nationalities to desert and join the Germans”.

For generations who grew up after the Second World War, it can seem obvious that collaboration with the Nazis was the greater ill. That was simply not the case for most of the nationalities who had faced horrific repression under Stalin’s regime, and for whom, at least at first, it would have seemed possible to welcome the Nazis as ‘the enemy of their enemy’.

All of this is complex and there seems little reason to believe that students will be encouraged to understand the reasons. Quite the contrary, and not only because the passages from the textbook shared by outraged readers are often manipulative and misleading.

Under Russian President Vladimir Putin, the Second World War has become a major part of Russian state narrative, with this leading to a whitewashing of Stalin’s crimes and effective rewriting of the many dark pages of the Soviet history of the time. The Kremlin has increasingly justified the notorious Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact and its secret protocols which made the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany allies for almost the first two years of WWII, and which carved up Poland between the two powers.

Russia has even used the courts to try to rewrite history with a Perm man, Vladimir Luzgin having been convicted and heavily fined for sharing a text which, quite truthfully, stated that both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany had invaded Poland in 1939 (details here).

There has been a steady move towards ‘rehabilitating’ Stalin under Putin, towards underplaying his horrific crimes against humanity, including genocide, and exaggerating (and misrepresenting) Stalin’s role in the Second World War and the eventual Soviet victory. It is almost certain that this narrative will form the background against which the false claims about Crimean Tatar collaboration will be wrongly perceived.

It is unclear how the textbook presents the Deportation, however since traditional remembrance events around the 70th anniversary of the Deportation were banned just months after Russia’s invasion and annexation, optimism does not seem warranted.

Moscow is, probably with cause, concerned that the main indigenous people of Crimea have so clearly shown that they identify with Ukraine and is seeking to deny their indigenous status.

It was the Mejlis, or representative assembly of the indigenous Crimean Tatar people who called the huge demonstration on 26 February 2014 which prevented Russia from orchestrating an apparent ‘Crimean move to change Crimea’s status’. Heavily-armed Russian soldiers without insignia seized control the next day. The Mejlis remained implacably opposed to Russian occupation, with this resulting in an ever-mounting offensive and, eventually, the Mejlis being banned as ‘extremist’.

The repressive measures have not only been against the Mejlis, but against very many Crimean Tatars. The Russian-controlled and Russian media regularly present arrests of totally law-abiding Crimean Tatars as though they represent some kind of Russian struggle against ‘extremism’ or ‘terrorism’. The aim there, and now with this new school textbook, is to justify repression by inciting enmity and distrust towards the Crimean Tatars.

Update Following the outrage over this book, the occupation authorities have announced that they are removing it from schools and will form a working group to ‘assess’ the offending parts.