• Topics / Human Rights Abuses in Russian-occupied Crimea

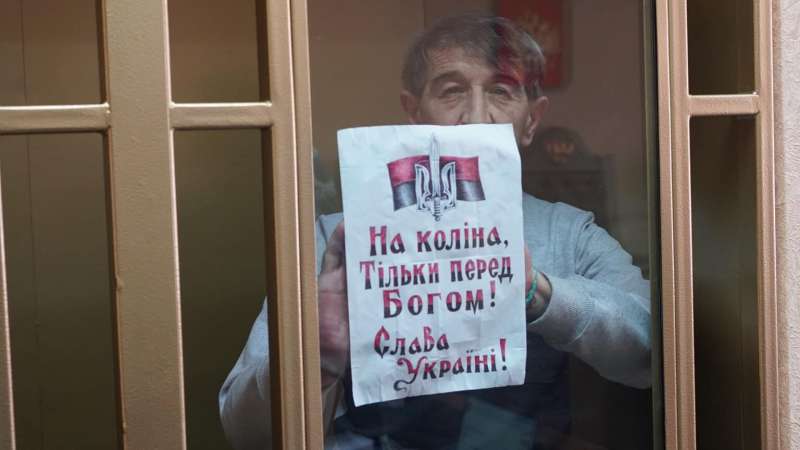

62-year-old Ukrainian political prisoner threatens to slash his wrists if Russia doesn’t release his medication

Almost a year after the FSB in occupied Crimea arrested Oleh Prykhodko on fabricated charges, a Russian prison is refusing to provide him with the medication for a kidney condition that he needs to be taking daily. This is either malice or an attempt to put pressure on the political prisoner, as the prison administration needs only hand Prykhodko the medicine that his daughter is sending. At the beginning of an aborted hearing on 1 October, Prykhodko threatened to slash his wrists if the medicine is not released within a week.

The eleventh hearing at the Southern District Military Court in Rostov (Russia) did not take place, supposedly because the prosecutor was on holiday. There was no good reason for prior warning to have not been received and Prykhodko’s lawyer, Nazim Sheikhmambet asked the court not to postpone the hearing. since Prykhodko’s wife and daughter had specially made the long journey from Crimea, but to no avail.

The court was due to continue examining the highly dubious ‘evidence’ from a memory stick and a mobile phone that the prosecution claims were found during the ‘search’ of one of Prykhodko’s two garages on 9 October 2019.

Prykhodko was initially charged with having planned to blow up the Saki city administration building on the basis of the explosives which the FSB claimed to have found. Then, three months later, it became clear that Prykhodko was facing an even more bizarre charge – of having planned to set fire to the Russian general consulate building in Lviv, Western Ukraine. The ‘evidence’ for this was from text messages on a BQ mobile phone,supposedly found in a wardrobe.

During the previous hearing on 21 September, defence lawyer Sergei Legostov repeatedly drew attention to the huge difference in time between outgoing and incoming messages (1 January and 18 September, respectively) in the alleged conversation by text messages.

Such discrepancies are of crucial importance in confirming the testimony given by both Prykhodko and his wife that they had never set eyes on the telephone in question before.

As reported, the defence has presented considerable evidence showing that Prykhodko had extremely limited technical skills, making it extremely improbable that he would have chatted by text messages on a mobile phone and that he would have even known where to insert a memory stick, let alone save something on it. Nobody had ever seen him use anything but the Blackberry telephone that he had owned for years and which he used to make phone calls.

The memory stick, which contains a text which Russia has on its enormous list of prohibited materials, was also ‘found’ in the bottom of a flower pot looking suspiciously clean and undamaged, despite Lyudmila Prykhodko watering the plant every couple of days.

Such ‘evidence’ could get Prykhodko a very long sentence, with the fact that it is all so obviously fake clearly regarded as unimportant. This was true of the alleged explosives as well. How else can one explain why the two FSB officers, both former Ukrainian Security Service turncoats, left after one of them (Volodymyr Stetsuk) supposedly ‘found’ explosives in a bucket in one of Prykhodko’s two garages? The only possible reason for not searching the second garage was that they already knew that they would find nothing.

As with virtually all political trials of Crimean Tatars, there is a clear divide in this case between real witnesses and the ‘secret witnesses’ produced by the prosecution. These include somebody under the pseudonym ‘Pankov’ who was first questioned in June and whom the prosecutor decided to question away in September, by video link from Crimea. Lawyer Legostov objected, noting that the prosecution had refused to organize video link for his colleague in the case, Sheikhmambet, and that criminal proceedings to not allow for such a repeat interrogation. The prosecutor claimed this to be ‘supplementary’ which was, indeed, what it proved to be with this mystery individual who may or may not even know Prykhodko now claiming that he knew Prykhodko had explosives. During the previous questioning, this same secret ‘witness’ had claimed to have learned that Prykhodko was planning terrorist attacks and had reported this to the FSB. The individual asserted at the last hearing that he had been told about the planned ‘terrorism’ several times, though could not remember when. One question from the defence, specifying when exactly, the individual refused to answer, claiming that would identify him. He asserted that Prykhodko had asked him to find people to help his unlawful acts, and was then unable to explain why Prykhodko should have thought he could find such people. Legostov quite legitimately wished to know when the individual had been informed that he would be questioned again. The man claimed to not remember, to “have problems with dates”, and then the prosecutor objected, with the court forcing the question to be withdrawn.

This ‘witness’ claimed that he had met Prykhodko near a church, but was unable to say which, or where it was. He also stated clearly that Prykhodko had not threatened either him, or his family. Asked why then he was hiding his identity, he said “well, it’s such a civic position”.

Russia is basing sentences of 10 or 20 years on such ‘secret witnesses’ whose identity is not revealed to the defence and whose testimony cannot be verified. It is particularly telling that this individual has even admitted the lack of legitimate grounds for such secrecy. Since his testimony is so glaringly different from that of all witnesses willing to testify under their own names, this is obviously suspect.

Among the many reasons for assuming that Prykhodko’s rights will be found by the European Court of Human Rights to have been gravely violated is the use of such secret witnesses. In an important judgement on 22 September 2020, (The Case of Vasilyev and Others v. Russia ). the Court found that there had been a violation of the applicants’ right to a fair trial in the use of anonymous witnesses without any grounds, and in the fact that one of the convictions had been based solely on such testimony.

While the FSB have come up with other ‘evidence’, all of this was obtained with serious breaches of criminal procedure and appears such as questionable as the ‘testimony’ of anonymous witness ‘Pankov’.

Prykhodko is charged under three articles of Russia’s illegally applied criminal code: Article 205 § 1 - planning terrorist acts – the Saki Administration in Crimea and Russian general consulate in Lviv; Article 223.1 (illegally preparing explosive substances) and 222.1 § 1 (purchasing or storing explosives). The only ‘proof’ of the planned ‘terrorism’ in Saki (near Prykhodko’s home) is from a bucket will of ‘explosive’ substances which the FSB allegedly found in one garage, without looking in the other. As for his grandiose plans for a ‘terrorist attack in Lviv’, the prosecution claims that he decided to do this in October 2019 and that he found “an unidentified individual” in mainland Ukraine, phoned him and then corresponded with him by text messages