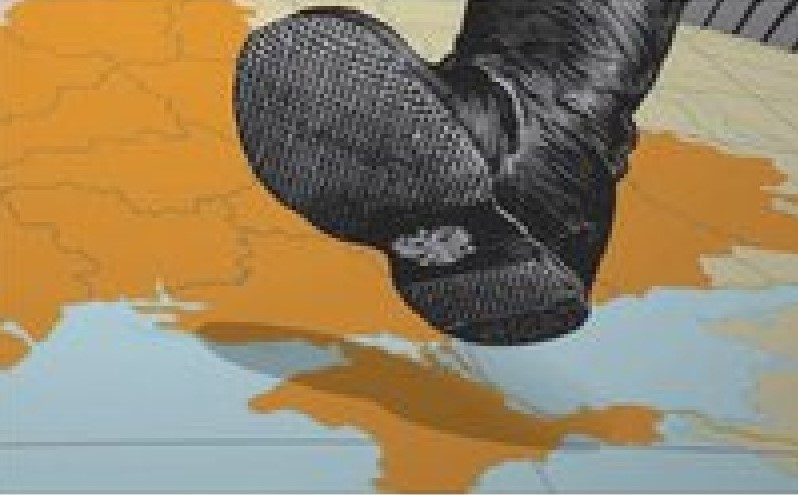

Ukrainians forced to take Russian citizenship, or lose their homes in occupied Crimea

In less than three months, Ukrainians who have not taken Russian citizenship face being stripped of their homes or land in occupied Crimea. This follows the brazenly illegal decree passed by Russian President Vladimir Putin on 20 March 2020, prohibiting those falsely dubbed ‘foreigners’ from owning land in around 80% of the peninsula, except for three regions without access to the Black Sea.

The move is yet another method by which the occupying state is forcing those Ukrainians who in 2014 refused to take the aggressor state’s citizenship, to either lose their homes or be forced to become Russian citizens. There are likely to be other motives, including straight plunder since the price is likely to be significantly lower than the land’s real value.

Refat Chubarov, Chair of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people, stated at the time of the decree that he saw it as aimed at speeding up colonization of Crimea. Russia, he said, was creating a supposed legal mechanism which it would claim creates conditions for bringing Russians to settle in Crimea. Roman Martynovsky, a lawyer from the Regional Centre for Human Rights, stresses that we would need to know the numbers involved to make any definitive statement. It is, however, difficult not to agree with Chubarov, he says, in that the process of stripping people of their land will have impact on the demographic situation in Crimea. It will later inevitably complicate the processes linked with reintegration after the occupation ends, as, he stresses, it will.

The occupation authorities have themselves said that around 10 thousand plots of land fall under the ‘decree’, while Martynovsky says that they have identified almost four thousand Ukrainian victims.

Putin’s decree formally extended Russia’s list of ‘coastal territories’ on which ‘foreign nationals, stateless persons and foreign legal entities” cannot own land. If Russia wishes to ban non-Russian citizens from owning land in Sochi, it may do so. It has no right as an occupying state to include any part of Crimea in this list. The Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilians expressly prohibits such actions on occupied territory, with Article 53 stating:

“Any destruction by the Occupying Power of real or personal property belonging individually or collectively to private persons, or to the State, or to other public authorities, or to social or co-operative organizations, is prohibited, except where such destruction is rendered absolutely necessary by military operations.”

Oleksandr Sedov, from the Crimean Human Rights Group, explains that the occupation regime will begin stripping people of their land from 20 March this year. They will receive notification, with an amount of money in roubles named, if they are living in Crimea. They will, formally, be able to appeal against the decision, but a just ruling from a Russian-controlled ‘court’ should not be expected. While Russia ‘guarantees compensation’, Sedov says he can give a 100% guarantee that the figure will be much lower than it should be. It is also quite unclear how they will pay such compensation to people living in mainland Ukraine.

Although many people are now trying to pre-empt this development, whether by selling the property themselves or, perhaps, by accepting Russian citizenship, a large number of Ukrainian citizens left Crimea because of their unconcealed opposition to Russian occupation. In those cases, the Ukrainians would themselves be in danger if they tried to enter occupied Crimea to organize a sale.

Sedov stresses that any attempt to take people’s property away from them is a war crime and something that people can approach the European Court of Human Rights over. If there are such cases, these will certainly be brought before the International Criminal Code which recently stated that it had found evidence of war crimes and crimes against humanity in both occupied Crimea and Donbas. He says that if there are a lot of such cases, this will only strengthen Ukraine’s position.

That, however, will not help people get their property back, at least not until Russia’s occupation of Crimea ends. Sedov says that even a positive judgement from the European Court of Human Rights will only pertain to the money for the property.

For some, this may simply be a plot of land or flat that is easy to sell, for others, it is their family home which they never wished to sell, and certainly not to the Russian occupiers who seized their Crimea and are calling them ‘foreigners’.