Memorial: 63-year-old Ukrainian imprisoned solely for opposing Russian occupation of Crimea

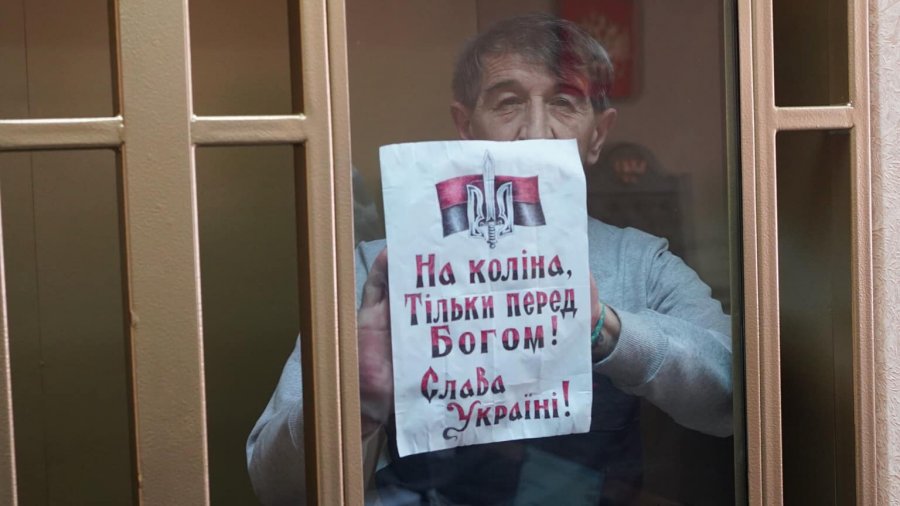

The authoritative Memorial Human Rights Centre has declared Oleh Prykhodko a political prisoner, finding the case against the 63-year-old Ukrainian activist falsified and lacking in any elements of a crime. It is clear, the human rights group states, that Prykhodko was arrested and tried purely because of his political views.

The Ukrainian activist from Crimea is described as having “a vehemently negative position with respect to Russia’s annexation of the peninsula”. Having studied the case, Memorial HRC is convinced that his prosecution is linked with his pro-Ukrainian views. The human rights groups points to “significant discrepancies” in the case, as well as important evidence that can, with a high level of probability be considered to be fabricated. Fingerprints were not taken from the items allegedly found in Prykhodko’s garage, while the investigators did not even attempt to explain how Prykhodko was supposed to have obtained elements which are not freely on sale. They assume that the enforcement officers could have fabricated the telephone correspondence which contained the details about the supposed ‘terrorist act’.

Memorial HRC points out many of these circumstances have been seen in earlier cases involving Ukrainians tried for such alleged sabotage or terrorist plans, with the men in those cases also recognized political prisoners.

Since the case and its discrepancies have been reported many times, the following in places adds to the details given in the Memorial account.

Prykhodko was charged under three articles of Russia’s criminal code: Article 205 § 1 - planning terrorist acts (supposed plans to blow up both the Saki Administration in Crimea and Russian general consulate in Lviv); Article 223.1 - illegally preparing explosive substances; and 222.1 § 1 (purchasing or storing explosives) The charges were based solely on a bucketful of ‘explosives’ allegedly found in Prykhodko’s garage; and a telephone and memory stick that the FSB claimed to have found in the Prykhodko home. Prykhodko and his wife stated from the outset that they had never set eyes on any of these items, and there were other compelling grounds for believing that they had been planted.

According to the sentence, Prykhodko is supposed to have planned to blow up the Saki Administration building and to set fire to the Russian General Consulate in Lviv, and these ‘crimes’ had not been carried out due to circumstances beyond Prykhodko’s control. He had allegedly created one explosive device, and begun another; and had also purchased and kept explosive substances at his home.

Prykhodko was initially arrested on 9 October 2019 and charged with planning to blow up the Saki City Administration building. Prykhodko’s open opposition to Russian occupation had already led to earlier administrative prosecutions and he had every reason to except FSB visitations and searches, with this just one of the reasons why it was inconceivably that he would have held a bucket full of explosives in his garage. Another was that he is a blacksmith and metalworker by profession, who used both garages for welding and soldering work. He would have been suicidal to hold flammable substances near his equipment.

An additional reason for disbelieving the prosecution’s case is that the FSB refused to search Prykhodko’s second garage, behaviour that can only be explained if they knew they would find nothing, because they had brought the illegal substances with them.

As Memorial noted, there was no attempt to explain how the 63-year-old was supposed to have obtained items that were not available in ordinary shops.

During the evening after Prykhodko’s arrest, a person claiming to be a doctor took a biological sample from Prykhodko’s mouth. This was illegal, without a lawyer present, and makes the claim that DNA was found on the alleged ‘evidence’ highly suspect. .

The second charge only became clear three months later. Prykhodko was accused of having planned to set fire to the Russian general consulate building in Lviv, Western Ukraine, with the alleged ‘proof’ of this lying in a telephone and a memory stick. It was claimed that Prykhodko had discussed, via telephone and text messages, plans to carry out a terrorist attack on the Russian consulate in Lviv. There is considerable testimony from friends and colleagues confirming that Prykhodko had extremely basic knowledge of how to use either a smartphone or a computer.

More importantly, the defence succeeded in debunking the prosecution’s claims regarding the alleged conversation and text messages. They demonstrated, via billing records, that the telephone, allegedly found during the search, and the one supposedly used by the person in Lviv, had been bought in the same Simferopol shop shortly before the supposed communication. The lawyers also showed that the phone call which was supposed to have been made by this mystery individual from Lviv, during which he had hinted at Prykhodko’s purported terrorist plans, had, in fact, come from the Kherson oblast, more precisely somewhere around the administrative border with occupied Crimea. Such a call could easily have been made by the FSB, which would explain why the latter showed no wish to identify the mystery person, or to try to ascertain why the phone which was supposed to be Prykhodko’s was registered in another name altogether. The defence also produced an experiment demonstrating that Ukrainian sim-cards work in occupied Crimea, but mean that any call or message is receiving as from a Ukrainian user. This presumably means that there would be nothing to stop all of the alleged text message ‘correspondence’ to have been carried out in occupied Crimea.

Memorial points out that, out of four telephones found in the Prykhodko home, only one was taken away. The sim-card in this telephone had been registered according to fictitious passport details. The memory stick allegedly found had material regarding methods of preparing homemade explosive devices, as well as maps, photos, etc. of the Saki Administration building.

The human rights group notes also that the phone calls allegedly recorded are from private conversations where Prykhodko expressed very negative views about Russia’s politics, etc., and made emotional threats, full of expletives, about setting fire to an embassy. Memorial stresses that there was absolutely nothing in the conversations to suggest any specific plans for real actions.

The only such specific details are from the alleged text messages which, as pointed out above, could very easily have been fabricated. It was these which were found in an expert assessment to “be of a terrorist nature”.

Prykhodko was tried at the same Southern District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don (Russia) which has been involved in most politically-motivated trials of Crimean Tatar and other Ukrainian political prisoners. In December 2020, prosecutor Sergei Aidinov claimed that the charges had all been proven and demanded an 11-year sentence and fine of 200 thousand roubles. On 3 March 2021, presiding ‘judge’ Alexei Abdulmazhitovich Magomadov; together with Kyrill Nikolayevich Krivtsov and Sergei Fedorovich Yarosh, found Prykhodko guilty of all charges, however removed the charge under Article 223.1 (preparing explosives) as being time-barred. They sentenced him to five years’ harsh-regime imprisonment with the first year to be served in a prison, the worst of all Russian penal institutions. He was also ordered to pay a still prohibitive 110 thousand rouble fine. The sentence will be counted from when Prykhodko was first taken into custody, i.e. 9 October 2019. The sentence was significantly lower than that demanded by the prosecutor, but then the judges can have been in no doubt that they were sentencing an innocent man to a term of imprisonment that he may not survive.

PLEASE WRITE TO OLEH PRYKHODKO!

Letters send an important message, telling him that he is not forgotten, while also showing Moscow that the ‘trial’ is being followed. Letters need to be in Russian, and on ‘safe’ subjects.

Sample letter

Привет,

Желаю Вам здоровья, мужества и терпения, надеюсь на скорое освобождение. Простите, что мало пишу – мне трудно писать по-русски, но мы все о Вас помним.

[Hi. I wish you good health, courage and patience and hope that you will soon be released. I’m sorry that this letter is short – it’s hard for me to write in Russian., but you are not forgotten. ]

The envelopes can be written in Russian or English as below.

344022, Россия, Ростов-на-Дону, ул. Максима Горького, 219 СИЗО-1.

Приходько, Олегу Аркадьевичу, 1958 г.р.

[In English: 344022 Russian Federation, Rostov on the Don, 219 Maxim Gorky St, SIZO-1

Prykhodko, Oleg Arkadievych, b. 1958 ]