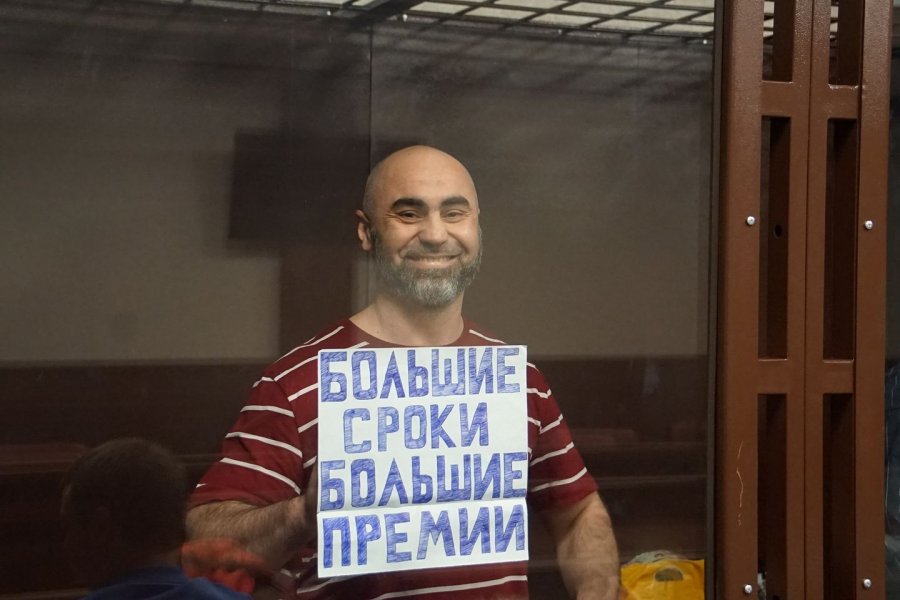

Huge sentences against Crimean Tatar political prisoners mean fat bonuses for Russia’s FSB

Sakira Kantimirova was just 10 months old when the Russian FSB came for her father Eldar Kantimirov and seven other Crimean Tatars. If the current Russia regime has its way, she will be 15 when her father, a recognized political prisoner, returns from the imprisonment in Russia that for all too many Crimean Tatar families has become a second deportation.

During one of the court hearings, Kantimirov held up a placard with the words: ‘Long sentences – big bonuses’. This bitter assessment of the ‘Russian justice’ illegally imposed since Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea is almost certainly correct. Russia’s use of a flawed and probably politically motivated Supreme Court ruling in 2003 as the excuse for sentencing men to 20 years or more on terrorist charges, without any crime or whiff of terrorism, is known to bring the FSB bonuses and other goodies in Russia, while requiring minimum effort. In occupied Crimea, the same charges – of involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir , a peaceful transnational Muslim organization that is legal in Ukraine – are also used by the occupation regime as a weapon against the Crimean Tatar human rights movement, and against individual Crimean Tatars, like Kantimirov, who refuse to look the other way when men are persecuted for their faith and civic activism.

Eldar Kantimirov turned 41 on 10 July 2021, in a Russian prison. Like most of the Crimean Tatars whom Russia is persecuting. Kantimirov was born in exile in Uzbekistan, following Stalin’s Deportation of the entire Crimean Tatar people in 1944. The family were only able to return in 1992, when Eldar was 12. As a teenager, he showed great promise as a sportsman and was both Crimean boxing champion, and a prize-winner in Ukraine’s championship. He needed to choose after school whether to follow a sports career or study further, and chose the latter, studying mainly at the Islamic University in Kyiv. Although a specialist in Arabic Studies, he had his own small business in order to support his family (he is married with four children.)

Like very many political prisoners, Kantimirov had earlier attended many political trials of other Crimean Tatars and in other ways shown his solidarity with victims of repression. In October 2017, he was detained and fined for a solitary picket under a placard reading ‘Crimean Tatars are not terrorists’. A month later, his family were first subjected to an armed search, during which technical devices were taken away. The FSB also turned up on many occasions, putting psychological pressure on Kantimirov and his family, and hinting of the consequences if he did not leave Crimea.

When none of this worked, the FSB turned to more savage repression. Kantimirov was one of seven men seized during armed raids and supposed ‘searches’ of Crimean Tatar homes in three parts of Crimea on 10 June 2019 and accused of involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir.

Kantimirov is the youngest of four men from the Alushta region ‘tried’ as a group, with two of the men – Lenur Khalilov and Ruslan Mesutov accused of ‘organizing a Hizb ut-Tahrir group’ (under Article 205.5 § 1 of Russia’s criminal code). Kantimirov and Ruslan Nagayev are charged under Article 205.5 § 2, with involvement in this unproven ‘group’. All four men are also charged, under Article 278, with ‘planning to violently seize power’.

In declaring all four men political prisoners, the renowned Memorial Human Rights Centre pointed out that the men were charged under Russia’s terrorism articles, without actually being accused of terrorism and are imprisoned for the “non-violent exercising of their right to freedom of conscience, religion and association”.

Although Kantimirov was especially active and attended political trials, all of the men had shown support for other political prisoners and their families. Memorial HRC noted that “the convenient and customary accusation of involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir has become a weapon for crushing solidarity movements in Crimea”.

There are additional reasons in this case for suspecting the FSB’s motives. The persecution of Khalilov, the Head of the ‘Alushta’ religious community, and Mesutov, an active member of the community, coincided with a systematic offensive against the community, aimed in part at seizing control over the 19th century mosque which was legally allocated to them almost 30 years ago. Both men are now facing sentences similar to the 19 years imposed on Muslim Aliev, a fellow member of the community, recognized political prisoner and Amnesty International prisoner of conscience.

The entire ‘case’ against them appears to be based on illicit tapes of conversations which FSB-loyal ‘experts’ assess as required, and on the ‘testimony’ of anonymous witnesses.

Crimean Solidarity reports that since his arrest Kantimirov has been diagnosed with the first stage of Parkinson’s Disease.

The ‘trial’ of the four men is now coming to an end at the notorious Southern District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don, with the prosecutor Yevgeny Kolpikov having already demanded horrific sentences (Kantimirov – 14 years; Nagayev – 15; Mesutov – 18 and Khalilov – 19). The next hearing is on 5 August.

Please write to Eldar Kantimirov; Lenur Khalilov; Ruslan Mesutov and Rustem Nagayev!

The letters tell them they are not forgotten, and show Moscow that the ‘trial’ now underway is being followed. Letters need to be in Russian, and on ‘safe’ subjects. If that is a problem, use the sample letter below (copying it by hand), perhaps adding a picture or photo. Do add a return address so that the men can answer.

The address is below and can be written in either Russian or in English transcription. The particular addressee’s name and year of birth need to be given.

Sample letter

Привет,

Желаю Вам здоровья, мужества и терпения, надеюсь на скорое освобождение. Простите, что мало пишу – мне трудно писать по-русски, но мы все о Вас помним.

[Hi. I wish you good health, courage and patience and hope that you will soon be released. I’m sorry that this letter is short – it’s hard for me to write in Russian., but you are not forgotten. ]

Eldar Kantimirov

344022, Россия, Ростов-на-Дону, ул. Максима Горького, 219 СИЗО-1.

Кантимирову, Эльдару Шкуриевичу, 1980 г.р.

[In English: 344022 Russian Federation, Rostov on the Don, 219 Maxim Gorky St, SIZO-1

Kantimirov, Eldar, b. 1980 ]

Lenur Khalilov

344022, Россия, Ростов-на-Дону, ул. Максима Горького, 219 СИЗО-1.

Халилову, Ленуру Абдурамановичу, 1967 г.р.

[In English: 344022 Russian Federation, Rostov on the Don, 219 Maxim Gorky St, SIZO-1

Khalilov, Lenur, b. 1967 ]

Ruslan Mesutov

344022, Россия, Ростов-на-Дону, ул. Максима Горького, 219 СИЗО-1.

Месутову, Руслану Аметовичу, 1965 г.р.

[In English: 344022 Russian Federation, Rostov on the Don, 219 Maxim Gorky St, SIZO-1

Mesutov, Ruslan, b. 1965]

Ruslan Nagayev

344022, Россия, Ростов-на-Дону, ул. Максима Горького, 219 СИЗО-1.

Нагаев Руслан Серверович, b. 1964

[In English: 344022 Russian Federation, Rostov on the Don, 219 Maxim Gorky St, SIZO-1

Nagayev, Ruslan, b. 1964]