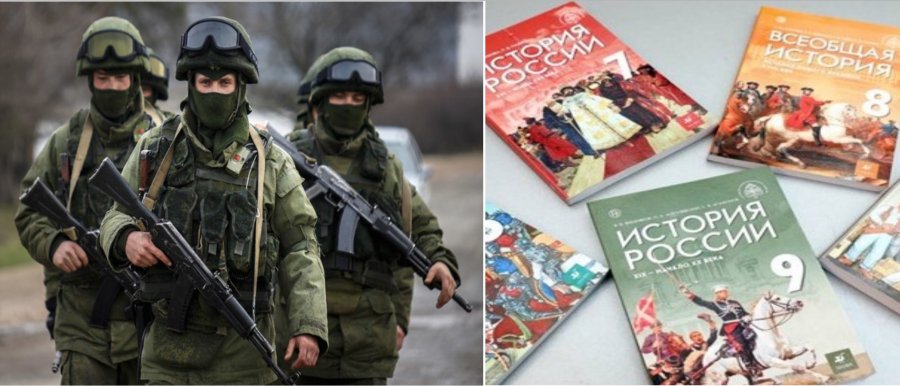

Russia did not invade Crimea in new school textbooks edited by Putin adviser

Russia’s Ministry of Education has approved school history textbooks which present Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea as “a peaceful process” which did not involve the deployment of a single Russian soldier. This, moreover, is only one of the omissions of “evident historical facts” in the final part of a ‘textbook’ written by a publicist mainly known for his work in Russian state-controlled media, including RT and ‘Sputnik’ and his unwavering pro-Kremlin position. The new textbooks have coincided with a presidential decree issued by Vladimir Putin on 30 July 2021, creating a ‘Commission on historical education’ made up, not of historians, but of representatives of various state bodies, including the FSB [Security Service], Prosecutor General’s Office and Investigative Committee. The commission is supposed to ensure “an aggressive approach to upholding the Russian Federation’s national interests linked with preserving historical memory and the development of educational activities in the area of history”. It will also analyse “the activities of foreign structures” claimed to harm Russia’s interests and prepare “counter-propaganda measures”.

Since both the textbooks and the Commission are aimed at ensuring – or policing - a single ‘correct’ approach to history, it is of particular concern that the Commission is to be chaired by and the textbooks are under the editorship of Vladimir Medinsky, now Putin’s adviser and the Head of the Russian Military History Society. The latter was created by President Putin in December 2012, in order to “consolidate the forces of state and society in the study of Russia’s military-historical past and counter efforts to distort it”. In 2015, Medinsky attacked the head of Russia’s State Archives, Sergei Mironenko when the latter, entirely accurately, stated that the Soviet WWII legend about Panfilov’s 28 heroic guardsmen was a myth. By March 2016, Mironenko had been dismissed from his post, and by April that year, the State Archives had been placed under Putin’s control. Medinsky is on record for a highly specific attitude, to Joseph Stalin and to monuments in memory of the murderous Soviet dictator, and recently claimed that the huge number of Soviet civilian deaths in WWII was “monstrous genocide”, which was no less terrible, he added, than the Holocaust. The Russian Military History Society, under his leadership, has been involved in scandalous attempts to rewrite Soviet history, such as the excavations at Sandarmokh, aimed at ‘proving’, against all evidence, that at least some of the mass graves are of Soviet soldiers killed by the Finnish Army, not of victims of Stalin’s Terror.

Several history teachers or historians have noted that the textbook, aside from its final section, has obviously been written by professional historians and does not omit the darker aspects of the Soviet period. That, however, is a far cry from encouraging students to consider all aspects and reach their own assessment. Tamara Eidelman, a well-known history teacher and author, points out that, even where students are encouraged to discuss some contentious parts of history, the material is presented in such a way as to lead students to draw one single conclusion. She cites, for example, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. This was officially a non-aggression agreement between the USSR and Nazi Germany signed on 23 August 1939, however the pact’s secret protocols, carved up what was then Poland between two collaborating and invading states. The material in the textbook, Eidelman notes, makes it inevitable that students will conclude that this was a brilliant diplomatic triumph. This, in turn, is precisely the position that Medinsky has publicly taken.

At least one Russian (Vladimir Luzgin) has already been convicted on criminal charges for reposting a text which correctly states that the USSR and Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939. It has now also become a criminal offence in Russia and occupied Crimea to liken the USSR and Nazi Germany, and bookshops and libraries are, reportedly, in a frenzy trying to understand how many books they need to purge.

The new textbooks are not the first attempt to present one correct view of Russian history, but they seem more likely to have a chilling effect on teachers and students, both because of the increasingly repressive laws stifling freedom of expression about the Second World War and in general, and because of the new commission. As Eidelman warns, teachers could well end up being the target of complaints (otherwise known as denunciations) for views that deviate from that considered the only correct position.

Whether or not teachers choose to tell students of alternative points of view, they will themselves be aware that such alternatives do exist. Very few school students are motivated enough themselves to look beyond a textbook, or have parents, etc. who will broaden their outlook. The vast majority will know only that ‘history’ which they gleaned from the textbook.

For that reason, the last part of this ‘textbook’ is especially alarming. St. Petersburg historian Konstantin Severinov, who praised the professionalism of the first sections of the textbook calls this concluding part “politically biased and one-sided, concealing a part of obvious historical facts”.

Eidelman called the final section “beyond good and evil” and said, in an interview to Ekho Moskvy, that she could not describe it except in language that is not permitted in broadcasts. The reason is very simple. Even if the treatment of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the Soviet annexation of the Baltic Republics (also treated as a ‘diplomatic triumph’) foists particular, highly contentious, interpretations, the first part of the book has, nonetheless, been written by professional historians.

The final part was written by publicist Armen Gasparyan. He is best-known as a journalist, who has worked for state and pro-Kremlin media, like ‘Russia Today’ [or RT]; Voice of Russia and ‘Sputnik’. A swift Google search shows that, at least since Russia’s annexation of Crimea, Gasparyan has been very active in parroting the Kremlin’s position on Crimea; historical memory; the West, etc. There was no resistance, he claims, in Crimea, except that of Russians against the Ukrainian authorities. After Putin’s first foray into articles on ‘history’, Gasparyan wrote that “Vladimir Putin makes it clear that in the struggle for memory about the valiant achievements of the people, our country will not retreat”.

Judging by the examples that Eidelman and others give, it would seem that Gasparyan has simply copy-pasted assertions from publicist texts in the new Russian school ‘textbook’. The latter reads, for example, that Putin “made it clear that Russia does not intend to accept the arbitrary behaviour of the USA and NATO, Putin’s speech vividly showed that the time when you could not consider Russia has passed”.

It cannot be said that there is anything new about Russia’s presentation of the events of February – March 2014. Grave distortion of the facts, including through omission of critical details, has been in the textbooks available in occupied Crimea for some time. In a textbook seen back in 2020, there is no mention of Russian soldiers at all, nor of the armed paramilitaries whose abductions, torture and at very least one horrific murder were very widely reported by the world media. Children are told that “on the basis of the results of a referendum (96% ‘for’), the peninsula on 21 March 2014 joined the Russian Federation. Crimea, whose territory had, without any grounds, been handed to Ukraine in 1954 by Nikita Khrushchev, returned to the Russian Federation”. (more details here).

By 2021, the number of possible criminal charges a person can face for not repeating this and other official lines from current Russian historiography has increased considerably. And, most alarmingly, there will now be a ‘commission’, headed by the general editor of the textbooks, and including the FSB and other enforcement bodies to police this new ‘single correct view’ of history.