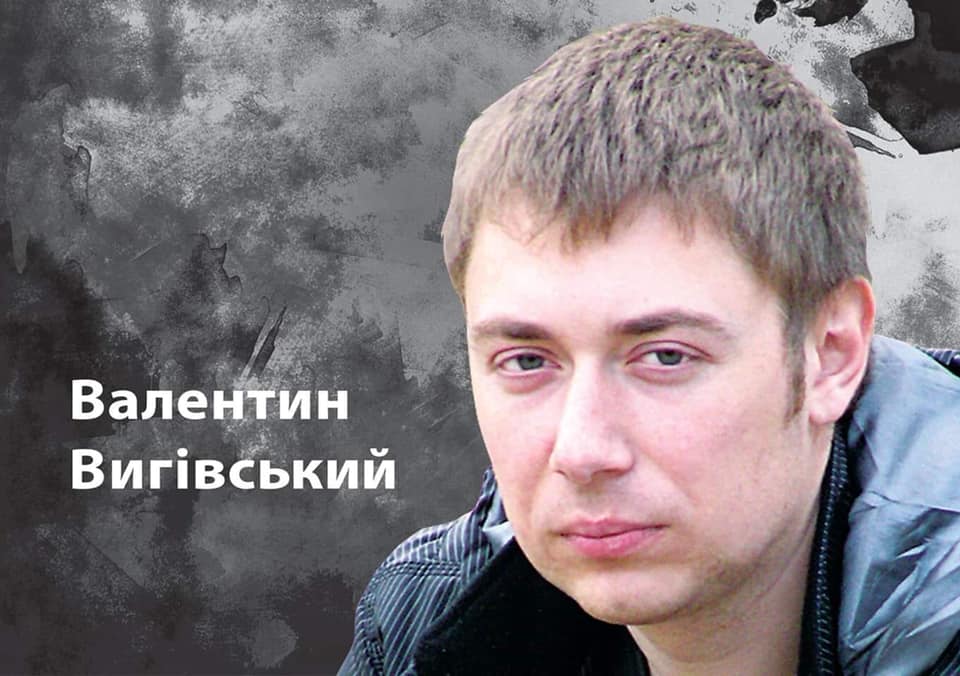

Valentin Vyhivsky: Eight years of torture in Russian captivity for being Ukrainian

It is exactly eight years since Russia’s FSB abducted Valentin Vyhivsky from occupied Crimea and took him to Moscow, where he was held incommunicado for around eight months and savagely tortured. Although the Ukrainian political prisoner is now in a Russian prison colony, there remains no let-up in Russia’s cruel torture. Seemingly quite the contrary. On 7 August, Valentin’s mother reported that Russia had imposed “total isolation”, with Vyhivsky being deprived of even the opportunity to correspond with his family and others. Some of the restrictions may not be specifically directed against Vyhivsky, with new rules having generally made it harder to send or receive letters. According to Natalya Demina, who has often written to Valentin, you cannot send books at all, and journals can only be sent in parts or not at all. Vyhivsky has spent a substantial part of the eight years since 17 September 2014 in total, or near total isolation, and is now being held in an information vacuum at a time when his only information about Russia’s war against his country will come from the Russian propaganda media.

In February this year, the world reacted with horror to Russia’s horrific crimes against Ukraine and its citizens. In fact, however, many of the crimes have been ongoing since 2014. As well as military aggression, the abductions and total lawlessness, the torture and insane ‘trials’ began back in 2014, and never stopped.

Vyhivsky is one of many men and some women whom Russia seized back in 2014. Some, like Ukrainian filmmaker Oleh Sentsov and civic activist Oleksandr Kolchenko, were targeted for their opposition to Russia’s occupation of Crimea or for other specific reasons. In some cases, including that of Vyhivsky, being Ukrainian was probably enough, although Vyhivsky had also taken part in the 2013/14 Revolution of Dignity (the Euromaidan protests). Many of the political prisoners seized in 2014 have since been released, either for health reasons or as part of an exchange of prisoners. Vyhivsky is one of two Ukrainians (together with Volodymyr Shur) who were seized in 2014 and remain imprisoned. Both were accused of ‘spying’ with this enabling Russia to hold their ‘trials’ behind closed doors and make it next to impossible to even fully understand what they were charged with.

Such secrecy makes it difficult to claim 100% certainty that there were no grounds for the charges. There would, however, have been no need to illegally imprison Vyhivsky and hold him without access to the consul and independent lawyers, and without any contact with his family, for eight months had there really been some substance to the ‘spying’ charges.

Valentin has now spent much longer in Russian captivity than his grandfather, a victim of Soviet repression. He recently turned 39 quite alone in a Russian prison in Kirov oblast, thousands of kilometres from his family, including the son he last saw when the latter was five years old.

Vyhivsky may have seemed an easy target for the FSB who had probably been aware of the young aviation fanatic even before 2014. Aviation had been a lifelong passion, and although he was unable to work in the field, Vyhivsky devoted a lot of time to reading about aviation issues and chatting with other enthusiasts on the Internet. Many of them were in Russia, and it seems likely that one of these people was either working for the FSB, or was threatened by them with trouble because of her contact with a young Ukrainian and former Maidan activist. This woman claimed that she urgently needed money for a relative’s cancer treatment, but could not come to mainland Ukraine herself, due to her line of work (presumably in defence). Unfortunately, Vyhivsky believed her and, having managed to get her the money, set off on 17 September 2014 for Crimea which was already under Russian occupation.

He vanished more or less on arrival, and his family began desperately trying to find out what had happened. It was only on 6 October that Ukraine’s Foreign Ministry ascertained that he had been ‘detained’, although not his whereabouts. Although he was once, about a month later, able to send a letter to his family, this contained almost no information, except that provided by the return address which told them he was being held in Moscow.

He was initially charged with ‘illegally receiving and divulging commercial, tax or banking secrets’ (article 183 of Russia’s criminal code). At some point, this was changed to the much more serious charge of trying to gather Russian state secrets to pass on to the Ukrainian Security Service [SBU].

It was the FSB who first reported that Vyhivsky had been sentenced to 11 years in a maximum security prison on 15 December 2015. The FSB claimed that Vyhivsky had come to their attention in 2012 and was suspected of gathering information containing commercial secrets through bribes, as well as information containing state secrets in order to pass them to a representative of a foreign state.

He was alleged to have “recruited employees of the aviation and space part of the Russian military industry to gather secret technical documentation on leading promising designs and pass them to him for financial remuneration”.

The FSB’s claim that Vyhivsky had ‘confessed’ to the charges when captured in Crimea fails to explain why they illegally took him to Moscow and held him incommunicado for eight months. It was only on 27 May 2015 that the Ukrainian consul was able to visit Vyhivsky, although then, and then a month later, when his mother was allowed a visit, two guards were present, stopping any subject concerning the charges and Vyhivsky’s treatment. He managed to tell his mother only that they know how to persuade you”. In a later visit, she learned that such ‘persuasion’ included two mock executions in a forest, and other forms of torture, with Valentin still bearing the scars of some of these on his body.

Although Russia could not maintain a total information blockade after the original sentence and he finally received an independent lawyer, Ilya Novikov, the latter was forced to sign an undertaking not to divulge any information about the appeal which was rejected on March 31, 2016. It is very likely that the information that was thus kept secret and ignored by a Russian court included details about the torture used to ‘persuade’ Vyhivsky to confess.

The secrecy has continued, as has Vyhivsky’s isolation. It is possible that the revelations about the torture as ‘method of persuasion’ during his mother’s visit in early 2018 prompted the prison authorities to intensify repressive measures. They began coming up with punishments on any pretext, with these making it possible to hold him in solitary confinement and restrict further visits. Even before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, he was prevented from having any real contact with other prisoners and held in an almost total information vacuum.

PLEASE write to Valentin!

It is important to show him that he is not forgotten, and even if he does not receive the letters for several months, they show Moscow that its treatment of Vyhivsky is under scrutiny. Letters need to be in Russian, and any political subjects or reference to his case should be avoided. If possible, include an envelope and some thin paper as he may well try to reply.

If Russian is a problem, the following would be fine, maybe with a photo or card

Здравствуйте, Валентин!

Желаю Вам здоровья и терпения, и очень надеюсь на скорое освобождение. Простите, что мало пишу – мне трудно писать по-русски, но мы все о Вас помним.

[Dear Valentin, I wish you good health, courage and patience and hope that you will soon be released. I’m sorry that this letter is short – it’s hard for me to write in Russian., but you are not forgotten. ]

Address (Valentin’s year of birth needs to be given, as here)

Russia 613040, Utrobino, Kirov oblast, Prison colony No. 11,

Vygovsky, Valentyn Petrovych, born. 1983

[or in Russian) Кирвская обл. г. Кирово-Чепецк. д. Утробино ФКУ ИК-11 УФСИН Россия 613040

Выговскому Валентину Петровичу 1983 г.р.]