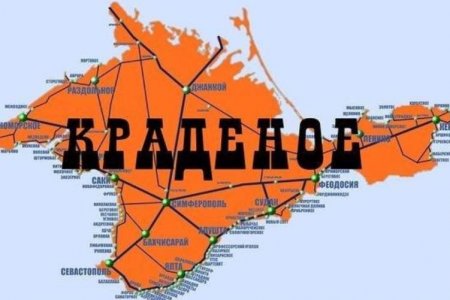

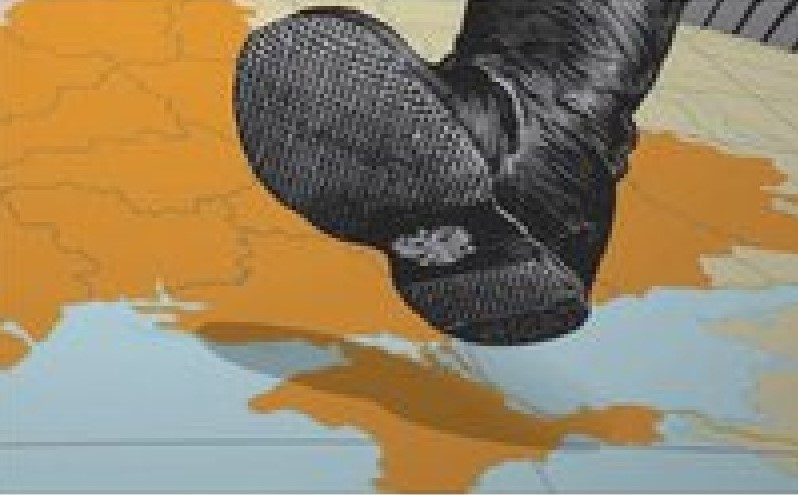

The Russian occupation authorities report that the number of plots of land “in the possession of non-residents of the Russian Federation has halved from 11,5 thousand.” What this actually means is that almost six thousand owners of land in Crimea, the vast majority of whom are Ukrainians, have effectively been stripped of their property rights. The same state-sponsored plunder is near guaranteed while any Ukrainian territory remains under Russian occupation.

The stripping of land rights in occupied Crimea is in implementation of an illegal decree by Russian President Vladimir Putin just over three years ago, on 24 March 2020, which came into force a year later. That document formally extended Russia’s list of ‘coastal territories’ on which ‘foreign nationals, stateless persons and foreign legal entities” cannot own land to cover around 80% of occupied Crimea, except for three regions without access to the Black Sea. The claim by a country that invaded and illegally annexed Crimea that Ukrainians living in their native land are ‘foreign nationals’ is profoundly cynical, as well as being in manifest violation of Article 53 of the Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilians.

Prior warning in this case was of little help since the owners of the land were forced either to accept Russian citizenship or sell their land, almost certainly at a loss and according to Russian law, something that very many would be unwilling to do. In a lot of cases, the land belongs to Ukrainians forced to leave Crimea following Russia’s invasion, with this probably creating still further obstacles.

The occupation report stated that the number of land plots in question had halved over the past three years and spoke of continuing “work aimed at terminating ownership rights of land plots belonging to foreigners in coastal areas”. The number has decreased from 11,5 thousand plots in 2020 to 5,803 as of 19 April 2023. The occupation authorities had, supposedly, carried out “explanatory work with owners, convincing them not to take the matter to the courts’. The threats were clear since those who had not sold the land themselves faced having it forcibly sold according to the value named by an occupation ‘court’, with the owner forced also to pay for the cost of such forced sale. The scope for corruption was huge, and the likelihood of ending up with very little extremely high.

The International Criminal Court recognized Russia’s ongoing occupation of Crimea as an ‘international armed conflict’ back in 2016, and encroachment by the occupiers on people’s ownership rights can be considered a war crime. Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion, human rights groups were encouraging all of those affected by the illegal decree to turn to the European Court of Human Rights. Even as a member, Russia often flouted this body, and has now formally withdrawn from the European Convention on Human Rights. That does not negate the need to establish the violation in European and international courts, but probably does mean that justice must wait until Russia is driven out of Crimea.