• Topics / Human Rights Abuses in Russian-occupied Crimea

After violently seizing Crimea, Russia accuses peaceful Crimean Tatars of ‘terrorism’ for defending political prisoners

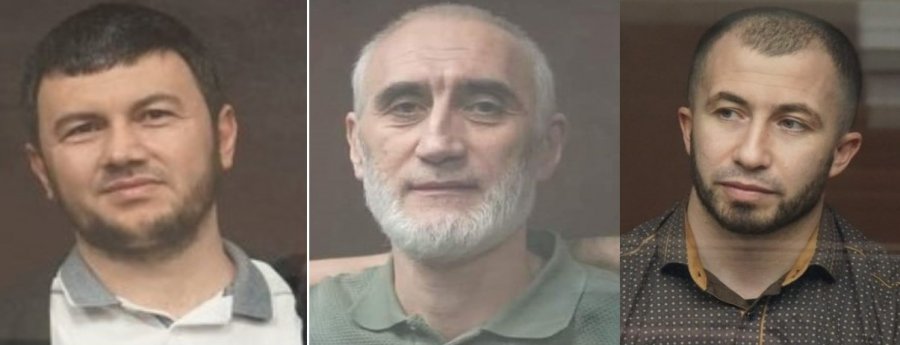

On 8 July, a Russian ‘court’ is expected to sentence three recognized Crimean Tatar political prisoners to huge terms of imprisonment. The charges are surreal and based on conversations about religion five years ago, planted ‘prohibited’ religious literature and on the ‘testimony’ of secret witnesses whose identity and motives for collaborating with the Russian FSB have long been exposed. All of the above explains why European and international bodies have long demanded the release of Oleh Fedorov, Ernest Ibragimov and Ismet Ibragimov. It will, however, almost certainly be ignored by two separate panels of judges at the Southern District Military Court which has become notorious for politically motivated sentences against Crimean Tatars and other Ukrainians All three men gave their final addresses to the court on 7 July, with Fedorov in particular pointing to the extraordinary cynicism in the fact that a country that invaded and annexed Ukrainian Crimea in 2014 should be accusing Crimean Tatars living peacefully in their homeland of ‘violently planning to overthrow the Russian constitutional order”.

In a powerful address, Fedorov began by identifying himself as a Muslim, Crimean Tatar and Ukrainian citizen recognized by the international community and human rights NGOs as a political prisoner. He spoke of how, on Russian television, they often show the events of [what Russia calls] ‘the Crimean Spring’. This is invariably presented as a joyous event, with happy, grateful Crimeans waving Russian flags. He has nothing against positive moods and joy, he says, but he is in favour of objectivity. “We are not shown how, suddenly, on city streets armed men in uniform but without insignia appeared on city streets and did not answer citizens’ questions as to who they were, where they were from and what they wanted. We are not shown how administrative buildings, military sites were seized by the armed ‘green men’ (as they were nicknamed), how military units and police stations were blocked. In such films and video clips, they don’t talk about how civilians began to disappear, with some found dead, and with signs of having been tortured. Many remain missing to this day. And they didn’t stop at that. Since that time, for 8 years already, totally innocent people, my compatriots have continued to suffer. I will not describe each event in detail – that is a separate tragedy although to varying degrees, linked with each other. Having been a witness of the events in 2014, it is important for me here to show that all of these ‘activities’ and the ‘actions’ of those participants were de facto “violent seizure of power and change in the constitutional order of a sovereign state, linked with terror, and including such components as fear; horror; violence; intimidation and terrorization. All of that constitutes Article 278 and Article 205.5 of Russia’s criminal code.

Not one of the participants in these events has faced any punishment to this day, and not one criminal prosecution has been initiated. On the contrary, they have monuments erected, are honoured with awards and medals….”

All of this, Fedorov goes on to explain, serves the interests of the current Russian regime and its leaders which has all but eliminated the political opposition, human rights organizations and the independent media.

In Crimea too, there is persecution of civic activists; religious figures; members of the indigenous peoples. The regime prohibited the Mejlis, or self-governing body, of the Crimean Tatar people, claiming it to be ‘extremist’, and has prohibited Hizb ut-Tahrir, the Jehovah’s Witnesses and others using the same methods, as well as putting pressure on the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

“Our criminal case is one of many such prosecutions. The FSB fabricates prosecutions on serious charges, with words like terrorism and extremism frightening people. Up until 2014, Crimeans did not come up against any demonstrations of terrorism or violence – we lived in peace and harmony. However, with the establishment of the new regime began an endless ‘fight against terrorism and extremism’. Over the eight years, there have been constant detentions, searches and arrests. Many Crimeans momentarily turned out to be criminals, and there was pressure against those who dared to support them and show any kind of help. Administrative prosecutions have frequently been brought against lawyers and human rights defenders. They face administrative arrest or are fined, and searches are carried out of their homes and offices. The same happens with those who arrive at courts, or [to stand outside] at searches and detentions. Any kind of means are used by the regime and security service who have fully understood their impunity and are trying to intimidate society in order to eliminate any demonstration of dissent at the lawlessness underway.

Fedorov noted how the indictment against him and Ernest constantly mentions the fact that the men had attended court hearings, searches and had helped ‘members of Hizb ut-Tahrir ‘ in prison. It is, he adds, such civic activism that the prosecution is claiming to be ‘criminal activities’.

“All of this lawlessness has led to Crimeans being deprived of the basic universal rights to one’s own views; to religious faith; to a civic position; the right to live a peaceful and just life without fear”.

Fedorov’s assessment of both the prosecutions of men on unproven charges of involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir and of the human rights situation in occupied Crimea is shared by Ukrainian and international human rights NGOs, and by the international community.

Russian prosecutor Valery Kuznetsov has asked that Oleh Fedorov (b. 1970) be sentenced to 16 years; Ernest Ibragimov (b. 1980) to 15 years. In the separate ‘trial’ of Ismet Ibragimov (b. 1988), prosecutor Sergei Aidinov has demanded an incredible 20-year sentence. The sentences sought and the difference in severity have nothing to do with any individual prosecutor and are based solely on the charges, with these also largely arbitrary. All of the men are accused of unproven involvement in the peaceful, transnational Muslim organization Hizb ut-Tahrir which is legal in Ukraine. Russia’s Supreme Court declared it ‘terrorist’ in February 2003 in a ruling that was kept secret until it could not be challenged. Since 2015, Russia has been using that ruling, which was never explained, as justification for arresting Crimean Muslims and imprisoning them for up to two decades on fictitious ‘terrorism’ charges. It increasingly targets Crimean Tatar civic activists and journalists who come out in peaceful protest against repression and show solidarity with political prisoners. This is the case with all three men in these two ‘trials’.

Oleh Fedorov and Ernest Ibragimov were arrested on 17 February 2021 in a particularly cynical attempt by the FSB to improve statistics on such arrests, while minimizing their workload. The work required is always fairly minimal in Hizb ut-Tahrir cases, as the charges, the FSB-loyal ‘experts’ and anonymous ‘witnesses’ migrate from case to case. In this case, however, it could essentially all be copy-pasted, as the Russian FSB had already used identical charges against eight civic journalists and activists. The charges against all ten men differed only as to whether the FSB accused them of having ‘organized’ a Hizb ut-Tahrir group, under Article 205.5 § 1 of Russia’s criminal code or merely of taking part in this fictitious group (Article 205.5 § 2). Given that Fedorov and Ibragimov were arrested three years after the other men, although on the basis of the same conversations five years earlier, the FSB presumably deemed it wiser to restrain their appetite and settle for the less severe charge of ‘involvement’. In the case of Ismet Ibragimov, however, he was on trial alone, so they called him ‘an organizer’ (under Article 205.5 § 1).

In both of these cases, as in all such conveyor belt ‘trials’ since the case of human rights defender Emir-Usein Kuku and five other Crimeans, the men have additionally been charged with ‘planning a violent seizure of power and change in Russia’s constitutional order” (Article 278). Not one of the armed searches of the men’s homes has ever found weapons or indeed any evidence of such ‘plans’, with the charge probably added to increase the propaganda effect of such cases.

More details after sentences are passed.

Please do write to the men! The letters demonstrate to them and to Moscow that they are not forgotten and that Russia’s persecution and the fate of its victims are under scrutiny. The addresses below will almost certainly remain current until after appeal hearings. Letters need to be in Russian, and on ‘safe’ subjects. If that is a problem, use the sample letter below (copying it by hand), perhaps adding a picture or photo. Do add a return address so that the men can answer.

Sample letter

Привет,

Желаю Вам здоровья, мужества и терпения, надеюсь на скорое освобождение. Простите, что мало пишу – мне трудно писать по-русски, но мы все о Вас помним.

[Hi. I wish you good health, courage and patience and hope that you will soon be released. I’m sorry that this letter is short – it’s hard for me to write in Russian., but you are not forgotten. ]

Oleh Fedorov

344022, Россия, Ростов-на-Дону, ул. Максима Горького, 219 СИЗО-1.

Фёдорову, Олегу Владимировичу, г.р. 1970

[In English: 344022 Russian Federation, Rostov on the Don, 219 Maxim Gorky St, SIZO-1

Fedorov, Oleg Vladimirovich, b. 1970

Ernest Ibragimov

344022, Россия, Ростов-на-Дону, ул. Максима Горького, 219 СИЗО-1.

Ибрагимову, Эрнесту Ильясовичу, г.р. 1980

[In English: 344022 Russian Federation, Rostov on the Don, 219 Maxim Gorky St, SIZO-1

Ibragimov, Ernest Ilyasovich, b. 1980

* pronounced, and therefore often written as, Fyodorov

Ismet Ibragimov

344022, Россия, Ростов-на-Дону, ул. Максима Горького, 219 СИЗО-1.

Ибрагимову, Исмету Таировичу, г.р. 1988

[n English: 344022 Russian Federation, Rostov on the Don, 219 Maxim Gorky St, SIZO-1

Ibragimov, Ismet Tayirovich, b. 1988]