At the beginning of 2022, our media team consisted of two people. In financial terms, 2021 was a challenging year for the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group: we had to reduce the staff and prepare half of the office for lease.

At the end of 2022, dozens of people were engaged in the work of the media department of KHPG. Some record interviews, edit and impose them, while others write news, analyze laws, prepare analytical articles, develop and edit websites, manage social media, draw illustrations, transcribe and create subtitles, translate, and design books for publication.

Most of these people have never met each other in person, but they are dedicated to the work that this difficult time requires, sometimes doing incredible things.

In this article, I will describe the most significant media projects that the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group launched in 2022 and a little about the people who made them happen. This is the second article in a series in which we talk about KHPG activities in 2022. In the first article, Yevhen Zakharov spoke about the humanitarian aid we have started to provide to those in need. We will continue to do this as long as it is necessary.

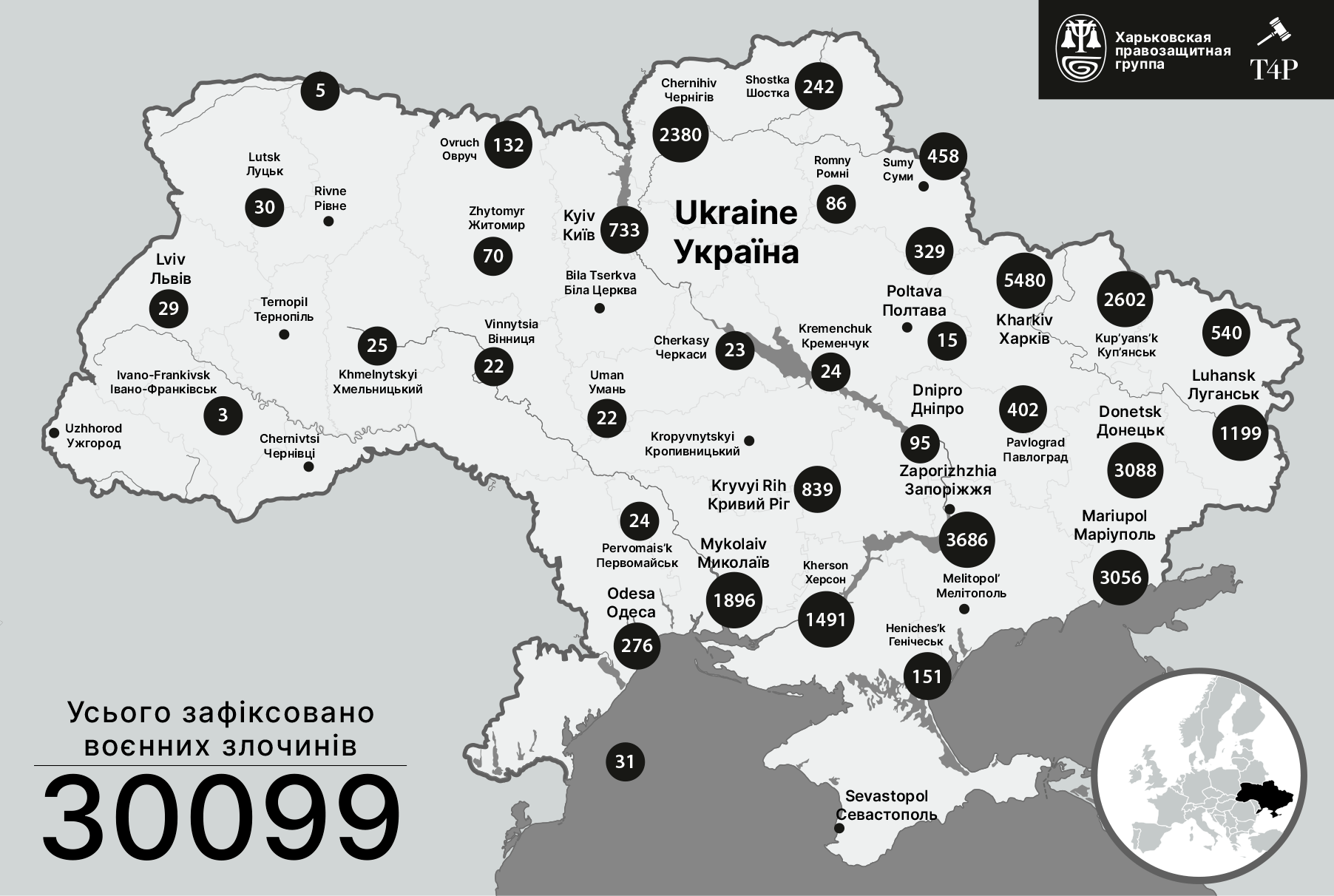

t4pua.org — a website describing in 7 languages the war crimes committed in Ukraine by the Russian invaders

As we had written many times before, in March 2022 the most significant human rights organizations in Ukraine launched a joint project to document numerous crimes committed by the Russian army in Ukraine using a single methodology and a single database. Two of them are among the human rights NGOs that won the Nobel Peace Prize in December 2022.

Our long-time partner, the European Union, represented by the European Commission and project manager Marco Ferraro supported the work of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. We should pay tribute to Marco: He did a lot to ensure that our work on documenting the war crimes was supported and the project passed successfully through the entire EU bureaucracy. Marco also facilitated one more idea. At a joint meeting, he once said: “You are doing a lot of excellent work, but it is not very well known. There are good materials in English on war crimes on KHPG's website, but not many people in Europe know about them. Here in Italy, for example, many people think that the Bucha massacre was staged.” That's how we came up with the idea to create a website for the T4P initiative (an acronym for “Tribunal for Putin” that Marco also proposed) in seven languages: Ukrainian, English, German, Italian, Spanish, Russian, and French. Marco also offered Arabic, but we decided against it. At the start, we weren't sure whether it was worth investing our limited resources in such a site. But we decided to try anyway.

This was an ambitious task for a human rights organization whose employees were scattered worldwide due to war. In 4 months, we managed it: we found the proper translators, the Juvenilia Agency designers visually developed our concept of the site, and their sketches were personally brought to life by Vitalii Novykov. Describing the website is like telling music, so I suggest you look.

Now we are facing new challenges related to regular content creation, high-quality translation, visualization of our data, etc. We keep going.

Voices of War — a collection of interviews with victims and witnesses of hostilities

You could see such interviews in many places and by many authors. Even sports journalists have retrained and are now filming military or civilians who have been in hot spots. But hardly anyone has 130 such interviews. Some of them, but not all, are published on our website. Processing so much material into a readable form is not as easy as it seems. The end of last year was particularly busy because we had to publish everything we had collected.

Of course, not all these interviews are mind-blowing, although many are. I am especially proud of the series of interviews about Mariupol. It includes more than 30 incredible stories told by eyewitnesses. The first printed collection of Voices of War we dedicate to Mariupol. I hope it will be published shortly.

We are the Ukrainian Memorial. Together with the Memorial organizations of other countries, we are launching a campaign to distribute our interviews in nine languages. Our friends from the Memorial units in the Czech Republic, Poland, France, Italy, and Germany translate the KHPG texts and subtitle our videos in their respective languages.

People in different parts of the country are recording the interviews; not all are our staff. For us, these interviews serve many purposes. It is material for documenting (when Mariupol was completely cut off from the world without communication, people who left the city were the only source of information about what was happening there), as well as an important historical source and just a fascinating read. Many interviewees also said it was a psychological relief to tell their stories and be listened to.

We continue to produce Voices of War and translate it into other languages.

Explanatory articles and Twitter in English

At the end of the year, we launched a new format for writing articles. We expose a problem through an interview, interrupting it with insets of explanatory text. Such insets usually contain explanations of the legal nature of a particular problem as simply as possible. For example, in an article about the new law on increased criminal liability for the military, we talk with a military lawyer and simultaneously explain what this law provides for. We are currently preparing a similar article about the Law on Media.

People started subscribing to our Twitter account even before the Russian invasion. Embassies and Western journalists did it, sensing incoming trouble. At the beginning of the war, we tried anyhow to inform about the developments in English. Now two staff work on our Twitter feeds regularly. We don't have many subscribers, but it's a reasonably refined audience: researchers, journalists, diplomats, and Western politicians.

We also launched our Instagram, created a Telegram channel, and are developing our YouTube.

Communication with the press and the best materials of KHPG

Immediately after the Russian offensive began, we started receiving inquiries from various world media. Everyone was interested in the general situation in Ukraine, our assessment of the human rights situation, and human stories. We tried to respond to all requests and helped as much as possible. We even had to explain to the MSNBC producer that KHPG does not have a Prosecutor General and that he should address to a different address.

Most of all, we communicated with the British inews publication. Using our consultations, they made a series of good investigations about the places where the Russian military forcibly held Ukrainians, recorded several interviews with our contacts, and reprinted one interview from our website.

Now I want to list some our materials from the past year that deserve your attention. Links provided only for articles available in English.

- Mass beatings in the prison colony No 25: a buried investigation?

A pre-war article about the investigation of the high-profile case of severe beating of prisoners in the Oleksiyivka prison colony. This colony is considered the most brutal in Ukraine, and the prisoners had never even dared to complain before. When they dared to complain for the first time in history, hoping for protection, the State Bureau of Investigation buried their hope. - A series of interviews with Mariupol residents in the Voices of War collection. Some of these interviews achieved hundreds of thousands of views.

- ‘The helicopter was clinging to the tops of trees.’ A wounded Azov regiment fighter's story about evacuation from Azovstal plant in Mariupol.

This is one of the first, if not the first, stories about the incredible MDI operation to rescue the wounded defenders of Mariupol. Previously, Zelensky said that 90 percent of pilots who flew these missions did not return, but our interview showed that the actual situation was much better. - When the Human Rights Commissioner Liudmyla Denisova was dismissed with a gross violation of the proper procedure, while many civil society activists supported this decision due to personal complaints, we gave Denisova the opportunity to speak out.

- Freedom of movement of persons liable for military service: old law, new hype, and communication errors

We sorted out (but not quite) the complicated story about the necessity for draftees to receive permission from the military enlistment office if they want to leave their domicile. - Vovchansk Aggregate Plant: a Russian torture chamber based on a Chechen pattern

We tried to compile information about the mysterious prison in Vovchansk. - “We want Ukrainian justice!”: Life prisoners did not escape from the abandoned Kherson detention center

More than 450 prisoners escaped from the detention center opened by the Russians, while only ten remain. Four of them are life prisoners. - A series of reports about the de-occupied Kharkiv region settlements: Vasylenkove, Ruski Tyshky, Slatyne, Korobochkyne, Zalyman, Kamianka.

- “They did not stop torturing me until I started shouting ‘Glory to Russia’.” Prisoners of the Kupiansk torture chamber tell about their experience in Russian hands

We were the first to talk to people forcibly held in the Kupiansk police station. They were released a month before the Ukrainian counteroffensive in the Kharkiv Region under a mysterious prisoner exchange. We provided them with legal and humanitarian assistance.

Another article on Kupiansk prison in English: 110 days in the torture dungeon - Muddy boots on the starry sky: Russians almost destroyed the world’s largest decameter-wave radio telescope

- ‘When will I get the money?’ What’s wrong with the promise of compensation from the ECHR to victims of war crimes

Our lawyer explains what's wrong with published in mass media promises to get money under the ECHR’s ruling. - The law banning the use of Russian-language information sources is senseless and extremely harmful

Article by Yevhen Zakharov. - Prison for disobeying orders. Discussing the strengthening of [Ukrainian] soldiers’ responsibility with a military lawyer

- Almost every school in Mariupol was damaged. A KHPG investigation

Using our database, we found that at least 52 out of 63 schools in Mariupol were destroyed. - War and freedom of conscience: Is it possible to refuse to serve in the Ukrainian Armed Forces due to religious beliefs? We talk to Dmytro Vovk, a researcher in the area of religion and law, and Yevhen Zakharov, director of KHPG

- “This is a veiled GULAG”. We visited a penal colony for people with disabilities; prisoners talked about torture

We also wrote about Oleksiy Dudin, a prisoner without legs in this colony, who does not have proper medical treatment. - Healthcare that kills: A prisoner with a severe oncological disease died behind bars without treatment

It is another story about a prisoner who was not treated. Despite our articles, lawyers' efforts, and the ECHR’s decision, Volodymyr Rubchenko died a day before his release. The Ukrainian prison system killed him. And, in fact, it was the Ukrainian state. - How students try to go abroad and whether it is legal to refuse them

While I tried to recall our materials, I realized how many there were. This is only a part of all the texts and videos our modest team has produced. And now, I want to list everyone who was a part of it in 2022.

- Iryna Skachko — journalist; a year ago, Iryna and I made up the entire media department of KHPG

- Yevhen Zakharov — Director of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group

- Hanna Ovdiienko — a lawyer, from time to time she writes good, well-pointed texts

- Taras&Oleksandr Viichuk — they live in Drohobych and record interviews for the Voices of War project

- Tamila Bespala — a lawyer, records video explainers on legal issues

- Vitaliii Novykov — administrator of KHPG web projects

- Taras Zozulinskyi — Lviv journalist, author of many of our interviews

- Olha Shevchenko — finds Mariupol residents who can tell amazing stories (she is one of them), creates subtitles for interviews, and sometimes records them herself

- Halya Koynash — a long-time and constant author of English-language news on the KHPG site

- Emiliia Prytkina — a very meticulous editor

- Maryna Harieieva — she is also a meticulous newswire writer

- Mykola Komarovskyi — a young and promising lawyer who created our channel on Telegram and continues to work on analytical materials

- Denys Volokha — the media director of KHPG

- Masha Krykunenko — manages our Instagram page and writes cool articles for the website

- Oleksii Sydorenko, Oleksandr Vasyliev, and the whole Magnolia TV team — our dear partners who regularly write interviews in the Kyiv region

- John Crowfoot — a translator into the English language and editor with vast experience

- Tanya Karliychuk — English language proofreader and translator

- Illia Husiev and Katia Okhrimchuk — authors of our English-language Twitter feed

- Serhii Prytkin — illustrator

- Vlad Dolzhko — author of reviews on the war crimes committed by the Russian invaders in the Kharkiv region

- Ihor Chernichenko — editor of the T4P website

- Volodymyr Noskov — journalist, author of several outstanding interviews for KHPG

- Andrii Didenko — author of articles and video materials about the prison system and interviews for the Voices of War project

- Vira Ammer — translator into the German language

- Bleuenn Isambard — translator into the French language

- Olha Tarnovska — translator into the Spanish language

- Michela Venditti — translator into the Italian language

- Oksana Komarova — photographer

- Serhii Okuniev — video materials author and editor

- Oleksandr and Denys / Juvenilia Agency — designers

- Sasha Savransky — a translator from the English language, proofreader

- Vitalii Konkin — a translator from the English language

- Anіa Zakharova — director of several videos

- Albina Lvutina — Mariupol journalist, author of several interviews

- Antonina Dembytska and Leonid Golberh — also authors of the interviews

- The teams of the French, Italian, German, Czech, and Polish Memorial organizations

We are grateful to our donors, who made all this possible; without their support, we would be able to achieve much less:

- The European Union

- The Czech NGO People in Need

- The Prague Civil Society Center

- The OpenArchive NGO

- The US Embassy in Kyiv

- USAID

- Dignity — Danish Institute Against Torture

- Individual donors