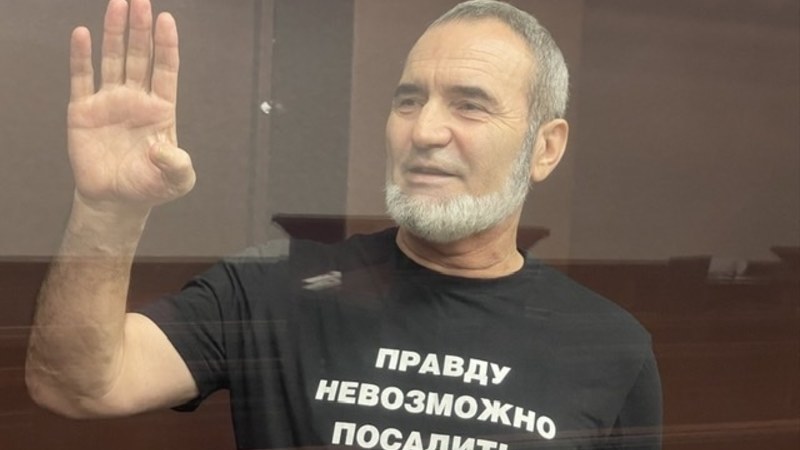

A court in Russia has sentenced Azamat Eyupov to 17 years in the harshest of Russian prisons, without any crime and in the full knowledge that this is an effective death sentence. The ‘trial’ of the veteran of the Crimean Tatar national movement and recognized political prisoner was especially shocking since the charges against him were based on a conversation that he did not take part in. This was demonstrated to the court and ignored, as were the 59-year-old’s life-threatening medical issues. The latter were, in any case, visible as Eyupov almost certainly suffered a stroke earlier this year, and, according to his lawyer, Emil Kurbedinov, is unable to use his right arm, is dragging one leg and has severely impaired speech.

No medical treatment was provided and this travesty of a trial was continued at the Southern District Military Court in Rostov which has become notorious for its politically-motivated sentences against Crimean Tatar and other Ukrainian political prisoners. On 19 July, presiding judge Kirill Kravtsov, together with Alexei Magomadov and Vladimir Tsybylnik found Eyupov guilty of the charges against him. He was sentenced to 17 years’ harsh regime imprisonment, with the first three years in a prison, the absolute worst of all Russian penal institutions. These sentences are all to a fixed pattern, with the court pretending that Eyupov could survive the 17 years, and adding a further one year term of restricted liberty at the end of it.

Although the charges against Eyupov fall under Russia’s norms on ‘terrorism’, he was not accused of any recognizable crime, nor, indeed, of anything that would be against the law in a democratic country. He was accused of unproven involvement in the peaceful transnational Muslim Hizb ut-Tahrir organization which is legal in Ukraine and which is not known to have committed any acts of terrorism or violence anywhere in the world. The Russian Supreme Court ruling in 2003 which declared it a ‘terrorist’ organization was deliberately kept secret until it was too late to challenge it, and Russia has never provided any convincing justification for the decision. This is one of the many reasons why the Memorial Human Rights Centre considers all those convicted merely of involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir, including Eyupov, to be political prisoners. In the case of Crimean Tatar and other Ukrainian Muslims from Crimea, Memorial HRC also points out that Russia is using these prosecutions to try to crush the Crimean Tatar human rights movement and that it is violating international law by using its own legislation on occupied territory.

Eyupov was accused of having been the ‘organizer’ of a supposed Hizb ut-Tahrir group (under Article 205.5 § 1 of Russia’s criminal code), as well as under Article 278, of ‘planning to violently seize power’. The latter charge may sound alarming, but is not based on any evidence of violence or even plans for such violence. Memorial has noted that the addition of Article 278 seems arbitrary, with the arguments for applying it effectively copy-pasted from those used for the first charge.

The defence is convinced that Eyupov was arrested on 17 February 2021 because of his refusal to give false testimony against other Crimean Tatars. He already had a heart condition then, and there was no justification for placing him in the appalling conditions of a Russian or Russian occupation SIZO [remand prison].

Eyupov was one of around 20 Crimean Tatars, most of them in their fifties and sixties, who took part in a peaceful picket on Red Square in Moscow on 10 July 2019, calling for an end to ethnic and religious persecution in Russian-occupied Crimea. They held placards reading “Our children are not terrorists”; “The fight against terrorism in Crimea is a fight against dissidents” and “Stop persecution on ethnic and religious lines in Crimea”, together with the photos of four political prisoners whose appeal was to be heard the following day. Although the men simply stood, apart from each other, but in a line, seven were detained and prosecuted under Article 20.2 of Russia’s code of administrative offences with supposed ‘infringement of the established procedure for holding a meeting’. The protest came almost exactly 32 years after Eyupov and other activists from the Crimean Tatar national movement held a large demonstration on Red Square demanding the right to return to their native Crimea after 43 years in enforced exile. That earlier protest was vital in gaining international publicity for the plight of the Crimean Tatars in the Soviet Union.

In 2019, the men were speaking out in support of Enver Mamutov; Rustem Abiltarov; Zevri Abseitov and Remzi Memetov whose sentences of up to 17 years without any crime were upheld, almost unchanged, on 11 July 2019.

Less than two years later, on 17 February 2021, Russia’s FSB came for Azamat Eyupov on identical charges to those against the men whom he had defended. Eyupov had also taken part in many other single-person pickets and flash mobs in support of political prisoners, and also regularly attended political court hearings.

The link between Eyupov’s earlier civic activism and his arrest seems clear and is also typical of Russia’s persecution of Crimean Tatars in occupied Crimea.

Eyupov was added to ‘a case’ which has already resulted in monstrous sentences against three recognized political prisoners from Bilohirsk (Russian Belogorsk): Enver Omerov and his son Riza Omerov, and Aider Dzhapparov. The three were sentenced to 18; 13 and 17 years, respectively, on 11 January 2021, with these sentences upheld by the court of appeal in March 2022. Eyupov was one of six men from different parts of Crimea arrested a month after the initial sentences, after ‘armed searches’ which again targeted civic activists. The armed and masked enforcement officers, as always, illegally prevented lawyers from entering, and in several cases, including that of Eyupov, the ‘prohibited’ religious literature supposedly ‘found’ was planted by the officers.

There seem no real grounds for accusing a person of either being ‘the organizer’ of a Hizb ut-Tahrir group or merely of ‘involvement’ in one, however the difference in sentence is significant. The fact that Eyupov was accused of the more serious charge of being an ‘organizer’ is especially cynical and not only because he was arrested two years after the other men in the same ‘case’. The charges were also based on an illicitly taped conversation about religion and Russian persecution that Eyupov did not take part in. Independent experts have confirmed that the voice on the tape used to justify the charges against Eyupov is not his.

This testimony, given by a qualified expert, should have demolished the case. Instead the prosecution and court preferred to rely on the official and FSB-loyal phonographic ‘expert’, despite the obvious contradictions in this individual’s testimony. It is believed that the voice on the tape was that of an Uzbekistan national who was living in occupied Crimea at the time, but is no longer. The defence assume that “having not found him, the FSB decided to pin criminal charges on somebody else.” The calculation that the ‘judges’ will not ask inconvenient questions and will turn a blind eye to real evidence is, unfortunately, all too realistic.

Please write to Azamat Eyupov!

Letters tell him that he is not forgotten and ensure that both the prison staff and Moscow know that their actions are under scrutiny. Letters need to be in Russian, and on ‘safe’ subjects. If that is a problem, use the sample letter below (copying it by hand), perhaps adding a picture or photo. Do add a return address so that he can answer. The address below will be valid until after the appeal hearing which may well be over a year away.

Sample letter

Здравствуйте,

Желаю Вам здоровья, мужества и терпения, надеюсь на скорое освобождение. Простите, что мало пишу – мне трудно писать по-русски, но мы все о Вас помним.

[Hi. I wish you good health, courage and patience and hope that you will soon be released. I’m sorry that this letter is short – it’s hard for me to write in Russian., but you are not forgotten. ]

Address

344022, Россия,, Ростовская обл., г. Ростов-на-Дону, ул. Максима Горького, 219, ФКУ СИЗО-1

Эюпову, Азамату Серверовичу, г.р. 1963

Or in English

344022 Russian Federation, Rostov on the Don, 219 Maxim Gorky St, SIZO-1

Eyupov, Azamat Serverovich, b. 1963 ]