Media Detector also discussed with Mr. Zakharov the responsibility of Russia and its leadership for the War Crimes committed in Ukraine, the possibility of appealing to the International Criminal Court or of creating a Special Tribunal on the crime of Aggression, and whether Putin will suffer the fate of Augusto Pinochet or Slobodan Milosevic.

The 2022 Nobel Peace Prize

Many people in Ukraine have criticized the decision to award the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize to human-rights organizations from Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus. It was the latest example, in their view, of continuous attempts by international organizations to bring “fraternal nations” together and reconcile the victim with the aggressor. How do you feel about the Norwegian Nobel Committee’s decision and this criticism?

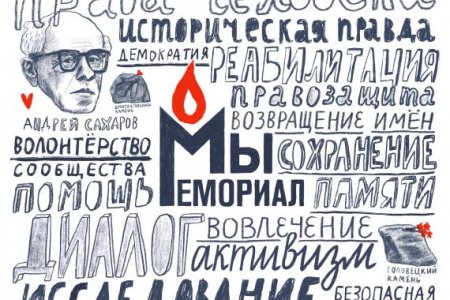

I think the Nobel Committee’s decision was quite reasonable and justified and that the reaction in Ukraine was inadequate. It’s not true that the Nobel Committee decided to bring the three countries back together again as a “family of fraternal nations”. One, the prize was awarded not to Memorial in Russia, but to the International Memorial Society. Whatever anyone says about it or what the Nobel Committee wrote in its press release [the release 7 October 2022 — states that the prize was awarded to the Russian Memorial, ed.], the prize was actually given to the International Memorial Society, which is made up of about thirty organizations in Russia, Belgium, France, the Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, and Ukraine.

Two, International Memorial, the Ukrainian NGO “Centre for Civil Liberties” and 60-year-old Belarussian human rights activist Ales Bialiatski do not represent any State. On the contrary, they have harshly criticized their respective States. That‘s why Belarusian and Russian human rights defenders are persecuted in their countries. This is not the case with Ukrainian NGOs because Ukraine is a democracy and the State and does not persecute civil society and its organizations. The Ukrainian State also violates human rights, however. The Centre for Civil Liberties and the Kharkiv Human Rights Group (KHPG) both defend people whose rights have been violated by the Ukrainian State. The Nobel Committee wanted to honour those who defend human rights from the State: it did not want to make these States join together in any sense. Those who see this award as an attempt to make these countries join together are mistaken.

What are the formal relations between KHPG and Memorial?

When the Nobel Prize was awarded, KHPG was the only Ukrainian NGO to be a member of the International Memorial Society. KHPG is, in fact, the Ukrainian Memorial: the Kharkiv Memorial has existed since August 1988 and was part of the All-Union [Soviet] Memorial Society [Voluntary Historical and Educational Society], which came into existence in 1987 and was formally registered in 1989. I was a member of Kharkiv Memorial from the very beginning, and since 1990 I have been its co-chairman. In 1992, we founded a separate legal entity, the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group (KHPG), which then joined the International Memorial Society. I have been a board member of the International Memorial Society since 1994. The Ukrainian Memorial organisation is, therefore, closely and directly connected with the International Memorial Society, which received the Nobel Peace Prize last year.

The Board of the International Memorial Society decided unanimously to hand the first replica of the Nobel medal and the first copy of the award diploma to the KHPG, a Ukrainian NGO. The Nobel Committee has the following rule: The Committee issues one original gold Nobel medal and a diploma; additionally, ten official replica medals made of another metal and ten official copies of diplomas can be distributed. Three copies are free; you must pay for the other seven if you want them. The International Memorial Society is a coalition of NGOs: it has many more than ten members in Russia and abroad, and all are entitled to these medals and diplomas. We were the first organisation Memorial member to receive an official replica of the Nobel Prize medal and diploma from the Memorial Board. We may say, therefore, that there are two Nobel Prize winners in Ukraine: the Centre for Civil Liberties [est. 2008] and the Kharkiv Human-Rights Protection Group (KHPG).

Have you decided how your organization will spend that part of the Nobel Prize money, which has also been transferred to Ukraine?

We shall receive half of the prize money awarded to Memorial. It’s a considerable sum — about EUR 150,000 [US $ 160,830]. The money hasn’t arrived yet. We have to wait because Memorial is currently facing a tough situation in Russia. We also have some funds received via other charitable programs.

We are acting only as distributors: the Board of the International Memorial Society must decide how to spend the money. It would be used, the Board decided, to help families who had lost a member since the war began. Why did we decide only to help the families of civilian victims? Because the State is legally responsible for caring for fallen soldiers’ families. Unfortunately, the State is not yet helping relatives of civilians who have been killed. If we can help, at least a little bit, we must do so. But the recently appointed board of International Memorial will have to approve the distribution policy for these funds in more detail, taking additional criteria into account.

The Tribunal for Putin (T4P) War Crimes database, to which twenty other Ukrainian organizations and the KHPG have contributed, now contains the names of more than 6,500 dead civilians. If we give families at least 3,000 hryvnias [$81] for each of those deceased civilians we will be able to help about 2,500 families. That is only 35% of the total number of civilian victims documented by us. Unfortunately, we don’t have enough money to help everyone. Therefore, we will need to consider additional criteria like whether it is a large family where a father or mother has died, a family with a disabled person or a person with a severe illness, or a family with lonely elderly people, etc.

Working with Ukraine’s law-enforcement agencies

Are there differences between the information in your database and the number of criminal cases opened by Ukraine’s law-enforcement agencies? Do you coordinate your efforts?

State law-enforcement agencies have opened quite a few such cases, but they lack the resources to conduct investigations. Let me say that no national law-enforcement system in the world could cope with so many crimes. It’s impossible. That’s why we must set priorities. Interestingly, Ukraine’s law-enforcement bodies have the same priorities as ours, although we did not coordinate with them beforehand.

The highest priority cases for law-enforcement that they investigate first are those in which civilians were killed or injured or people, both military and civilians, were illegally deprived of their liberty and taken prisoner, where they were tortured. Also, there are criminal cases of abduction concerning people who were abducted and taken to unknown places; we are also looking for information about them first. In addition, there are some very high-profile crimes with many victims, like brutal attacks on crowds of people in a building. We all know the examples: the attacks in Mariupol on a maternity hospital, an art school, and a drama theatre where up to a thousand people, including children, were hiding; the shelling of the Kramatorsk railway station, attacks on individual buildings in Odesa, Dnipro, Kharkiv, where many people were injured simultaneously. Then queues of people wating to receive humanitarian aid were shelled; there were attacks on humanitarian convoys and humanitarian missions.

There is a list of crimes we all single out because they are brutal, cruel, meaningless, and serve no military purpose. Both we and the State bodies believe such crimes should be investigated first. More precisely, the State should investigate, and we should collect information that will help the investigation. We collect it concerning such cases and aim to help law-enforcement agencies as much as possible.

It should be noted that the lion’s share of recorded crimes consisted of the destruction of housing and other property. That accounts for about three-quarters of the total number of crimes. It is true both for our database and for law-enforcement agencies. In cases of the destruction of property, our task is to ensure that criminal proceedings are opened and that the owners receive an excerpt from the State Unified Register of Pre-trial Investigations to confirm that they are victims. Law-enforcement agencies do not presently have the capacity or the resources to investigate these cases further. For example, the Investigative Department of the Security Service for the Kharkiv Region currently has only ten investigators dealing with such crimes.

Are you referring to all the crimes registered in the database, or only those related to the destruction of housing?

I mean all of them. About 10,000 of the crimes in our database were registered in the Kharkiv Region alone: some 4,000 were committed throughout the Region and about 5,000 in the city itself. More than 4,500 of the 8,000 residential buildings in Kharkiv have been destroyed or damaged, without including the Region as a whole. How can ten people investigate all these cases?!

That’s why we need to record all these crimes today. And we are helping law-enforcement bodies a great deal by doing so: we take photos and make videos to record the damage and destruction. When we can’t get close enough, we use a drone (quadcopter). We had two of them but donated one to the SSU. A KHPG staff member is using this drone to film places we cannot otherwise approach, reaching the roofs and upper floors of multi-storey buildings. We have to film and photograph the damage and destruction before such buildings are repaired or demolished.

Furthermore, we take part with law-enforcement agencies in other types of investigation. These are the priority cases I mentioned: we are involved in 350 such investigations, 67 of them in the Kharkiv Region. They are cases of people being killed, wounded, tortured, abducted, unlawfully detained or imprisoned and those, for instance, who were shelled while queuing at the Nova Poshta office to receive humanitarian aid ... We get on well with our law-enforcement agencies and our support expands their resources. There is a catastrophic lack of people who can deal with this activity.

Law-enforcement officers believe our lawyers to be professional and we are well-trained for such activity. For example, we know the rules governing the procedures for forensic photography: how to take photos, how to record and document these crimes. We use only digital cameras so as to attain the required quality. Since the Kharkiv Region was liberated, three of our groups have been making daily forays to record crimes and gather data.

Have you trained people since last year’s invasion? Or have they been working like this since 2014?

We did not train them when Crimea was annexed and parts of the Luhansk and Donetsk Regions were occupied. There was no political will to investigate such crimes then. They were not investigated in the same way.

We have lawyers on our team. Professional lawyers who represent the victim’s interests in court in criminal proceedings can also work as investigators: it’s part of their education and training. They all study together at law school, but some become prosecutors, others become defence lawyers. Still, they study the same subjects. For KHPG staff who are not lawyers, we hold training sessions on how to draw up formal records and take photos. We have taught them, and they are working well.

KHPG has expanded its staff and work

How many people work for the KHPG now?

A great many! The KHPG expanded significantly during the past year: it’s more than three times larger than it was. I find it hard to say exactly how many people are involved now.

For example, at the beginning of 2022 we had two people in our media department; today there are twenty. We created the Tribunal for Putin website about War Crimes in seven languages (Ukrainian, Russian, English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish). We started working on it during the war and launched it in September 2022. It includes articles about Russian War Crimes in Ukraine, short videos, and statistics which are updated daily from our database. This revealing information shows the current trends in the crimes being committed by Russians.

We are recording interviews for the “Voices of War” section on our website: today it contains more than 160 interviews in Ukrainian and some in Russian, as well. It’s a very important project. People who’ve suffered from Russian crimes can speak out and describe what happened to them. They gain closure after telling their stories. Some videos have attracted hundreds of thousands of views on YouTube. Since the New Year, we have been gradually translating these interviews into nine other languages — adding Polish and Czech to the seven languages already available on the Tribunal for Putin website. This is a joint project of the International and Ukrainian Memorial Societies. All the Memorial Societies across Europe (in Germany, France, Italy, the Czech Republic and so on) are translating these interviews into their languages. Then they post them on their websites and social media pages and distribute them to national media. In this way, we are spreading first-person accounts of what is happening during this war all over the world.

Are your staff mainly volunteers?

We do have volunteers, there were quite a few of them at the beginning of the war. Now I’m gradually transferring them to the status of paid staff: it’s hard to survive today only by working as volunteers. To pay for this, I’ve been trying to get as many grants as possible. I have a heavy workload as KHPG director, but what can you do? War is war, and it requires all of us to work as hard as we can.

Our main source of funds is a two-year grant from the European Union. We are also supported by Dignity, the Danish Institute Against Torture: they’ve funded three of our projects, enabling us to expand our activities. Previously, we could only provide legal assistance. With their backing, we have now started a psychological support service. It’s been in operation for five months in Kharkiv, and since the New Year we’ve been providing the same service in Kyiv and in western Ukraine (Lviv), not just for city residents but for people across both Regions.

We constantly send teams of lawyers and psychologists to monitor the situation in the north-eastern Kharkiv, Chernihiv, and Sumy Regions. Now we shall be doing this in the Kyiv and Lviv Regions, as well. Such trips uncover many new crimes previously undocumented or totally unknown. We are expanding our database and finding people who need legal and psychological assistance. Dignity, the Danish Institute Against Torture, are not just donors; they are partners and are actively involved in this project. I’m very obliged to them for their flexible and quick response to new needs and changes. We jointly decided that in certain situations, we need to organize legal, psychological, charitable, social, and even medical aid to the victims of War Crimes. We are trying to build a system that can supply all these types of assistance to anyone who applies to us for help. We are already working like that in Kharkiv and the number of applicants, cases, and appeals is rising all the time.

How do you document crimes in the newly occupied territories?

In the Ukraine-wide database of the Tribunal for Putin project, KHPG covers two areas: the Kharkiv Region and the city of Mariupol and its surroundings (Donetsk Region).

We selected Mariupol from the very beginning, in March 2022, when there was fighting there. Mariupol is the most challenging place to document War Crimes. There has been no direct communication with the city since 2 March: there are no reports in open sources and the available information has to be carefully checked. The primary way to gather information about Mariupol and certain other areas is through direct contact with victims and witnesses. Our Mariupol team, which is made up of people who left Mariupol, has already found more than 3,000 instances of War Crimes. That may seem few for the city; actually, it’s a lot. Today we know a great deal about Mariupol: what happened there and how, in what order events occurred, and the details of these crimes. We’ve conducted many interviews with those who escaped from the city to Ukraine-controlled territories; we’re now preparing a book of their stories and a documentary film based on these interviews.

Mariupol evacuees have been creating “I am Mariupol” centres, joining together in the cities where they live now. Today such centres exist in Kyiv, Khmelnytskyi, and Ivano-Frankivsk. Some five hundred people from Mariupol live in Lviv. We contacted them in advance and then went to Lviv in January 2023. We gathered together those who had suffered the most: we identified those who needed legal or psychological help; we recorded certain episodes for our database and confirmed some details. At present, this is the only way to record crimes committed in Mariupol. We’ve also travelled to the liberated territories. There we visited the places that suffered most: the cities of Okhtyrka and Trostyanets in the Sumy Region; the towns of Vovchansk, Izyum and Kupyansk, and particular villages (e.g., Kozacha Lopan and Slatyno) in the Kharkiv Region; and the village of Ivanivka in the Chernihiv Region.

Will there be a “Tribunal for Putin”?

There is a huge demand for justice in society. Is any chance of convicting the top leadership of Russia? Will a Tribunal for Putin really come into existence? Why is there a need for a separate tribunal, as called for by the European Union? Why can’t they hold a trial at the International Criminal Court?

One, if and when it receives the necessary evidence the International Criminal Court (ICC) will have every reason to bring Russia’s top political leadership to justice. It has been investigating the situation since early March last year. The problem is whether they can find the necessary evidence: such orders are concealed and often not committed to paper. Even if there are documents, they are classified. The likelihood of bringing the Russian leadership to justice will increase significantly, I believe, after they’re defeated. I’m sure they’ll be defeated. The only question is when, and at what cost.

Two, the tribunal proposed by the European Parliament is necessary because no criminal justice body can address the Crime Of Aggression. The ICC can only examine the Crime Of Aggression when both the aggressor and the country under attack have both ratified the Rome Statute and become full members of the ICC. Neither Ukraine nor Russia has ratified the Rome Statute. The ICC can prosecute Russia’s military and political leadership if it has evidence of their orders on their behalf, constituting the crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court. [On 17 March, just three days after this interview was first published in Ukrainian, the ICC issued arrest warrants against Putin and the Russian Commissioner for Children’s Rights. They were found responsible for the war crime of unlawful deportation of population and that of unlawful transfer of population from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation, to the detriment of the Ukrainian children involved, ed.] The ICC cannot prosecute Russia for the crime of aggression. The UN’s International Court of Justice, meanwhile, can consider the crime of aggression, but it is not a criminal court: it does not pass sentences. That’s why the idea of creating a Special International Tribunal on the Crime of Aggression arose.

We have examples of international tribunals, such as the Nuremberg Tribunal and the Rwanda and Yugoslavia tribunals. Are they similar to the proposed tribunal on the crime of aggression?

There can be no direct analogies, because there have never been international tribunals on the crime of aggression. The tribunals for Rwanda or Yugoslavia were created after a vote in the UN Security Council. This will never happen in our case because Russia will veto it. The only option is for the UN General Assembly to cast a two-thirds vote for the creation of such a tribunal. Then it will not matter that that the UN Security Council has vetoed such a tribunal. Our diplomats and those of the rest of the world are now working to achieve this.

Why can’t there be a tribunal for the crime of genocide? Lawyers worldwide are inclined to recognize this war as genocide against the Ukrainian people.

That is an even more complicated issue than the crime of aggression. I support this idea. While the European Parliament has adopted a resolution to set up a tribunal on the crime of aggression, it subjected it to the UN decision. I believe that if the UN does not approve such a tribunal, European institutions can create it themselves.

Will such a tribunal be legitimate?

Yes. But at the European level. This war is taking place in Europe and all participants, with rare exceptions (mercenaries or volunteers from Latin America or Africa fight who are fighting on the Russian or on our side) are European. There are very few outsiders. The majority taking part in the war, or who are its victims, are Europeans.

There’s also the option of a hybrid tribunal. The problem is that creating such a tribunal means allowing foreign investigators and judges to work in Ukraine. Our legislation and Constitution prohibit the investigation by foreigners of crimes committed against Ukrainians; only Ukrainian citizens can do it. And only Ukrainians should conduct court proceedings. To establish such a tribunal, it will be necessary to create another judicial chamber in Ukraine aimed at considering War Crimes, including both foreigners and Ukrainians. To do this we must change the Constitution, and that cannot be done under martial law. I would’nt reject this idea out of hand, because it could significantly boost the potential of both the investigation and judicial proceedings.

Do representatives of foreign law-enforcement agencies now work and record crimes in Ukraine?

They do, and they form another useful resource. There are no barriers to their work in this case. Foreign authorities can investigate crimes committed against their nationals. For example, two British volunteers were killed. The UK can now, on its own, investigate their deaths on our territory. We have to hand them all the information we know. Prosecutors in twenty countries are now investigating War Crimes committed against their citizens in Ukraine. There are dozens of victims from some countries. National courts in other countries can also considerWar Crimes against Ukrainians under the universal jurisdiction principle. They have the right to do so and can assume many cases. I think this resource can also be used.

In general, justice has no statute of limitations. This is a proper philosophical principle, and it is applicable to our situation. There is no statute of limitations for War Crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. People will never forget those who have done them such injustices. No matter how much time has passed, such crimes must be investigated and their perpetrators punished. Chilean dictator Pinochet was brought to justice, remember, although he was very old.

He was released from custody pending trial because he suffered from dementia.

They released him because they felt sorry for him. But Milosevic was not released, nor was Karadzic and many others. There was a certain Arnold Meri, a Hero of the Soviet Union and a cousin of Lennart Meri, the second president of independent Estonia, who took part in the deportation of Estonians to Siberia in 1949. When he was already well over 90, he found himself in the dock. [Meri died before he was sentenced, ed.]

Which brings us back to the crimes of the Communist regime. Unlike Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania there were no trials for such crimes in Ukraine. There should have been. If the crimes of communism had been judicially condemned in Russia, it would have prevented the current horrible developments. Such condemnation greatly influences the consciousness of society, as happened in Germany. At first, German society received the Nuremberg trials very poorly, with distrust and protests. But all these denazification procedures changed the Germans. Nothing like this happened in Russia, and we see the result: Ukraine became a victim of Russian aggression precisely because communism was not adequately condemned.

Is it too late now?

We could also hold an International Tribunal on the Crimes of Communism. Those who committed these crimes have already died. But it can be an ad hoc tribunal with a unique charter aimed at least to protect the good name of those who were proclaimed criminals in Soviet times. Im thinking of quite specific people.

People were shot or arrested, for example, for giving bread to peasants in Ukraine during the Holodomor (State-sponsored famine) in 1932-1933. During those two years, 200,000 people were arrested and shot or imprisoned in Ukraine. Most have still not been rehabilitated. Such a tribunal would be useful if only to tell their stories, to restore their good name, and to remind society that they were not criminals, but heroes who had tried to save their fellow villagers and thus fought against the cannibalistic policy of the USSR. It can be done even now.

Local and foreign HROs and the State

You said that human rights defenders are primarily in opposition to the State. Has the work of human rights defenders become more difficult during the war? Have your relations with the State changed?

I can’t speak about all human rights defenders: the behaviour and position of various human-rights NGOs in Ukraine differ. Our situation became more difficult because, until 24 February 2022, the KHPG did not hesitate to speak publicly about human rights violations. We have always believed it to be our duty. Sometimes, it was better to solve the problem without publicity; mostly we did not hesitate to speak out about anything we considered necessary.

That situation has now changed. The enemy can make [propaganda] use of everything we say against our State, Ukraine, and ourselves. Therefore, we have to think twenty times before deciding it’s worth talking about a certain matter in public. We still speak out if we consider the State is violating someone’s human rights in a way that tends to play into the hands of the enemy. We state our position and prove that such things should not be done. Unfortunately, State agencies make mistakes. We often address specific officials directly, asking them to change something or not to pass particular laws without public discussion. When we are certain the State is making a big mistake, we act publicly.

It’s hard for me to tell whether they listen to us. Sometimes, the State has corrected its mistakes. Our specific communications with the State, let me stress, exclusively concern the issues in which we are helping Ukraine’s law-enforcement agencies and nothing else.

Which government decisions during the war would you call mistaken?

There have been quite a few, unfortunately. But that’s a topic for separate discussion. We unreservedly support the government in its battle against Russian aggression.

Since the beginning of the war, there has been more than one scandal involving statements or actions by international institutions, including human rights organizations. For example, everyone remembers an Amnesty International statement that caused outrage in Ukrainian society. Do you think these organizations are effective? Do people trust them less these days?

I’ve discussed the Amnesty report extensively in Ukraine and abroad, and I think they made a mistake. It should be noted that our State also made mistakes and that Amnesty tried to point them out. We did not want to listen to their advice, but Amnesty continues to work and prepares new valuable reports and statements on these topics. Before that incident, all Amnesty’s previous reports were pro-Ukrainian, very substantial, and strong. When someone makes a mistake, everyone remembers the mistake and instantly forgets the good steady work and help that came before. In this case, I think, Amnesty did not communicate well; they could have done better. They even admitted that they made a mistake.

As for the general attitude towards international organizations, such incidents will not significantly affect their reputation: people in Ukraine trust expert Western institutions that study the war because they have much better capabilities. We cannot take satellite images to see everything from space; they can. We work on the ground: they see it all from above, from space. We must combine the two. Therefore, I would not unequivocally reject what they do. There are some complaints against them (I have some of my own), but we shall continue to work with many of these organizations.