In the territories it now occupied, Russia’s aims were to destroy all politically aware Ukrainians, intimidate the rest of the population, and force them to move to Russia or to parts of Ukraine where the inhabitants were ‘loyal’ to the Russian regime. Russian counter-intelligence divided Ukraine’s citizens into four groups, those who

1. merited physical destruction or elimination,

2. were to be oppressed and intimidated,

3. could be persuaded to collaborate, and

4. those already willing to collaborate.

We have no choice whether to fight or not because it is a war aimed at our destruction. If we do not fight, we will not exist. It is a war of attrition. If we exhaust ourselves before then, we will be gone.

We must rally again to avoid being exhausted earlier, as at the beginning of a full-scale invasion, believe in victory, and mobilize all resources.

The new unity of society to repel aggression is possible only in the paradigm of freedom: when the military is motivated to defend the country when volunteers can freely and quickly help the defence forces and civilians, when business can earn and invest in victory, when both business and state enterprises on a fair competitive basis can receive state orders and work for defence, when civil servants are not afraid to make decisions, when there is an independent court and the justice system works according to the principle of the rule of law, when law enforcement agencies do not engage in pressure, repression and corruption, but perform functions that belong to them.

We will consider the role that the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group (KHPG) chose for itself in the fight against the enemy, and then the terror that Russia unleashed on the occupied territories.

The KHPG approach to documenting crimes and helping their victims

The KHPG has formulated a comprehensive and holistic approach to collecting information about international crimes committed by Russians, documenting and analysing these crimes, and helping law enforcement agencies investigate these crimes. It also includes rendering legal, psychological, monetary, humanitarian, social, and medical assistance to victims of these crimes, as well as informing Ukrainian and international society about these crimes.

The collected information is entered into the database, whereby the event location is recorded (geodata or addresses of the crime), the date of the event, the type and description of the event, the object of the attack, and preliminary qualification of the crime under the Rome Statute of the ICC. Additionally, we enter the personal data of the victims, witnesses, and perpetrators, if they are known, and evidence of the crime in the form of media files (photos, videos), text documents, etc. Many organizations collect this information, including members of the “Tribunal for Putin” initiative. These NGOs cover the entire territory of the country. Today, the database contains approximately ninety thousand incidents of crimes committed by Russians. Based on our research and collected information, we preliminarily classified these atrocities as war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide.

Sources of information for the database are open information on the Internet and direct contact with victims and witnesses. Direct contacts make it possible to collect information and file a report about the crime to law enforcement agencies to investigate it. Therefore, it is essential to find victims of a crime and interview them to populate the database, open an investigation, and provide the victim with the necessary assistance.

In addition to the work of the KHPG reception desk, an important tool of such search is monitoring visits to settlements in the de-occupied territory, during which KHPG lawyers interview the victims and find out what types of assistance they need. In advance, the local self-government body announces the date and time of reception, and its social protection department employees call the victims and invite them to a meeting. The monitoring team includes two lawyers who receive people in parallel and a psychologist who provides rapid psychological assistance. At the same time, the fourth team member makes photo and video recordings of the destruction in the settlement for the database. Our team visits the same settlement as many times as necessary to interview all the victims living there.

KHPG started such monitoring visits on October 1, 2022. As of September 1, 2024, we made 417 visits and consulted over 9200 victims.

Following the priorities of the Office of the Prosecutor General, the KHPG lawyers prepared statements of crimes for national law enforcement agencies regarding:

- dead and wounded civilians;

- illegally deprived of liberty and missing civilians; and

- prisoners of war and civilian prisoners, subjected to torture in captivity and then released.

As of September 1, 2024, KHPG considers 3360 criminal proceedings in which the lawyers of the KHPG represent the victims, including cases of:

- 1719 missing persons;

- 285 tortured (including 62 cases of sexual violence);

- 638 killed civilians;

- 718 wounded civilians.

KHPG lawyers help the police and the State Security Service of Ukraine conduct investigative actions. Such assistance includes questioning victims and witnesses, organizing forensic medical examinations, identifying corpses, identifying suspects, etc. In particular, our lawyers identified nine perpetrators among Russian prisoners of war.

We offer victims of crimes comprehensive help. It includes humanitarian assistance (provision of one-time cash support, clothing, medicines, and household items), legal assistance (provision of legal advice, reimbursement of attorney services for representation in national bodies of Ukraine and Russia, international bodies, such as the UN Human Rights Committee, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detentions, the International Criminal Court), and psychological aid (payment for long-term and short-term psychotherapeutic consultations).

Collected information about crimes is summarized in analytical articles and submissions to the Prosecutor’s Office of the International Criminal Court. We have already submitted six such submissions: first and second, in which we qualify the actions of the Russians in Mariupol and the forcibly transferring of children from Ukraine to Russia as genocide; third, fourth, and fifth devoted to illegal deprivation of liberty, extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances as crimes against humanity; and sixth, describing shelling of civilian objects and the civilian population as a series of war crimes.

However, it is not enough to transfer this information only to specialists and those investigating crimes, both in our country and abroad. We must reach the mass consumer of information not only in Ukraine but also in other countries. That’s why we created a special war crimes site t4pua.org in seven languages: Ukrainian, Russian, English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish.

We also have the “Voices of War” project. We interview victims and witnesses of war crimes and other people who have something to say about the war — soldiers, volunteers, psychologists, journalists, artists, and musicians. We already collected more than three hundred of these interviews on our website and our YouTube channel. They are informative, tell a lot about what is happening in our country, and show the level of mutual assistance and solidarity between Ukrainians. They also demonstrate what kind of terror the Russian military instils in the occupied territories and how brutally they treat peaceful citizens. We translate the best interviews into other languages. Voices of war are now heard in nine languages.

Also, we are probably the only organization in Ukraine that regularly publishes information about Russian protests against the war in Ukraine. We have published a weekly digest of such protests since mid-March last year.

Finally, I want to stress that the individual components of our approach are very closely related to each other and support each other. We are interested in extending this approach to all ten Ukrainian regions where fighting occurred.

Assigned targets

Particular targets of the occupying forces were priests and pastors, journalists, businessmen & women, public figures, local deputies, staff of local authorities, rescue workers, border police, law-enforcement officers and, especially, former soldiers who fought in 2014-2021 against the occupying Russian forces. The invaders, it almost seemed, had ready-made lists of such people. They were kidnapped and disappeared. Or they were unlawfully arrested and detained in unofficial and frequently quite unsuitable premises. The conditions were themselves a form of torture.

Torture of detainees

The detainees were cruelly tortured to obtain useful information or induce them to collaborate. After the Kharkiv Region was liberated in autumn 2022, no less than 33 such torture centres places were discovered — in Izium, Kupyansk, Balakliya, Vovchansk and other locations. Descriptions of some of these places, and testimony from the victims may be found on the KHPG website.

Even in those rare cases when prepared rooms were used to hold people, they accommodated such a large number of prisoners that it was very difficult to be in the cells. For example, in Kupyansk, the torture cells were located in the premises of the temporary detention centre for 140 places, but more than 500 prisoners were kept there. There were nine men in the cell for two places.

The recorded testimony of victims makes it possible to identify at least the following aspects of the conditions in which people were detained as amounting to inhuman treatment:

- overcrowded cells and premises;

- unventilated premises;

- lack of daylight;

- lack or insufficient volume of food and drinking water;

- inappropriate conditions for visiting the toilet or lack of any such;

- keeping detainees handcuffed and blindfolded;

- lack of necessary medical care;

- unbearable cold in the premises.

The forms of torture were similar for many geographically remote places of detention, further confirming that the use of torture was systematic and deliberate. Testimony by victims indicates there were several widespread forms of torture:

- beatings of the victims’ face, head and body using arms (sometimes wearing special gloves), legs and other objects (gun butts, rubber truncheons, wooden bats, belts, etc.);

- electric shock torture using tasers or attaching live wires to the fingers, ears and nose of victims;

- slashing the ears and fingers of victims with sharp blades or attempting to cut off parts of the body, particularly ears, even if such attempts were not completed;

- fake executions by shooting.

In their depositions a considerable number of the victims note the particular cruelty of these forms of torture. Victims were beaten so severely that they lost consciousness. An electric current was so strong, one victim noted, that “my body crumpled up and foam came out of my mouth”.

If the purpose of the torture was achieved, the prisoners could be released from the torture chamber. But if they refused to kneel, or sing the Russian anthem, or shout “Glory to Russia!”, or continued to speak in Ukrainian, did the executioners simply believe that the prisoner had not broken down and continued to “pose a threat to the national security and defense of the Russian Federation” (the standard formula for refusal to cross the border of the Russian Federation, which is used even for women over 85 years old), they were transferred to one of the places of detention in the temporarily occupied territory or of the Russian Federation, and further they were detained “for opposing the SVO”, i.e. illegally. Because this qualification is absent in Russian criminal and administrative legislation.

As of September 1, 2024, the T4P initiative documented 1,585 incidents of illegal detention and deprivation of liberty of civilians, including 34 incidents involving children. 400 of them — in Kharkiv region, 216 — in Kyiv region, 209 — in Zaporizhia region, 166 — in Kherson region, 313 — in Donetsk region, 111 — in Chernihiv region, 101 — in Luhansk region, 30 — in Mykolaiv region, 19 — in Sumy region, 10 — in other regions.

Missing people. Enforced disappearances

Let’s consider the important example of Nikita Shkryabin, a 20-year-old student of the 3rd year of Kharkiv National University of Law named after Yaroslav the Wise. On March 29, 2022, according to witnesses, he was captured by Russian soldiers in the territory of his native village of Vilkhivka and taken away in a car. Since then, no one has seen him. It was not until many months later that his lawyer, Leonid Solovyov, was informed in Moscow that he had been detained for “actions against a special military operation”, and that he was in Russia. Where exactly — they did not inform.

Solovyov applied to the military department of Russia’s Investigative Committee for a criminal investigation to be initiated against Russian military personnel for holding his client so long incommunicado. Typically, the Investigative Committee rejected the application.

Solovyov complained to the garrison military court which, on 12 December 2022, “established” the following: Shkriabin was detained “for unlawful actions. At the same time, he is not charged in any criminal prosecution, and no investigation is being carried out. Consequently, he has no procedural rights, including the right to a lawyer. “ The appellate body confirmed this decision.

So, two court decisions stated that Nikita Shkryabin is in custody without any legal reason. The same can be said about thousands of other civilian prisoners who became victims of enforced disappearances. The case of Shkriabin is a typical example of enforced disappearance: the Russian Federation hid information about his whereabouts.

By definition, enforced disappearance is regarded as “the arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty by agents of the State or by persons or groups of persons acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which place such a person outside the protection of the law” (Article 2 of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances). According to Article 1 §2 of the Convention, “No exceptional circumstances whatsoever, whether a state of war or a threat of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked as a justification for enforced disappearance”. Under international law, enforced disappearance is a crime, and if the practice of enforced disappearances is widespread or systematic, even a crime against humanity.

As of September 1, 2024, 6,292 incidents of disappearances were documented in the KHPG and T4P databases, in which 7,615 people, including 187 children, went missing. Of these, 6,179 disappearances were preliminary classified as violent. The geographical distribution of the number of missing persons is presented in the table:

|

Region |

The number of missing persons |

Including children |

|

Kharkivska |

2610 |

88 |

|

Zaporizhzhia |

869 |

13 |

|

Khersonska |

718 |

4 |

|

Luhansk |

520 |

14 |

|

Donetsk |

2188 |

60 |

|

Kyivska |

210 |

4 |

|

Mykolayivska |

182 |

3 |

|

Chernihivska |

59 |

|

|

Sumy |

41 |

From the testimonies of the victims of enforced disappearances who were released, it is known that they went through the same path as those detained: placement in a torture chamber, torture, transfer to places of imprisonment in the Russian Federation or in the temporarily occupied territory.

The exact number of illegal detentions and enforced disappearances remains unknown, it is a priori more than the number of documented incidents. Some regions where illegal detentions and enforced disappearances took place remain under occupation, making any access to these areas impossible. The real numbers will become known after the complete deoccupation of these territories.

This enormous figure, 6,292 disappearances, represents only the tip of the iceberg. The number of enforced disappearances may in reality be much higher. As of the middle of August 2024, the authorities registered 37 thousand people as missing. Since not all relatives of the missing report their absence to the police, the figure may be higher still.

Unlawful detention or custody without a court order, and enforced disappearances that conceal the whereabouts of the missing person, are gross violations of human rights. They may be provisionally classified, under Article 7:1 [e] and Article 7:1 [i] of the Rome Statute, as ‘Crimes against Humanity’.

Deportation and filtration

Another terror tactic against the population of the occupied territories is enforced deportation to Russia. This occurs from ‘considerations of safety’ because Ukraine’s armed forces are about to attack, as happened in the Kherson Region, or on the pretext of saving people from the danger of remaining in a zone of active hostilities, as was the case in Mariupol (Donetsk Region). At times, it has happened for no good reason at all. Why did the Russians, for example, deport two thousand prisoners serving time in Ukraine’s prisons and penal colonies to Russia, or move several hundred patients there from mental hospitals?

In order to prevent Ukrainian citizens who do not support Russia from entering the country, everyone travelling to Russia must pass through ‘filtration’.

‘Filtration’ can be defined in the following way: it is a violent, unregulated screening of the personal data of detained people, their social contacts, views and attitudes towards the occupying state, their safety for the authorities or services of the occupying state, as well as their willingness and consent to cooperate with the authorities or services of the occupying state. Its purpose is to identify people with pro-Ukrainian views disloyal to the occupation regime, in particular those who consider themselves Ukrainians, refuse to obtain a Russian passport, and want to retain their Ukrainian citizenship in order to isolate or even destroy them.

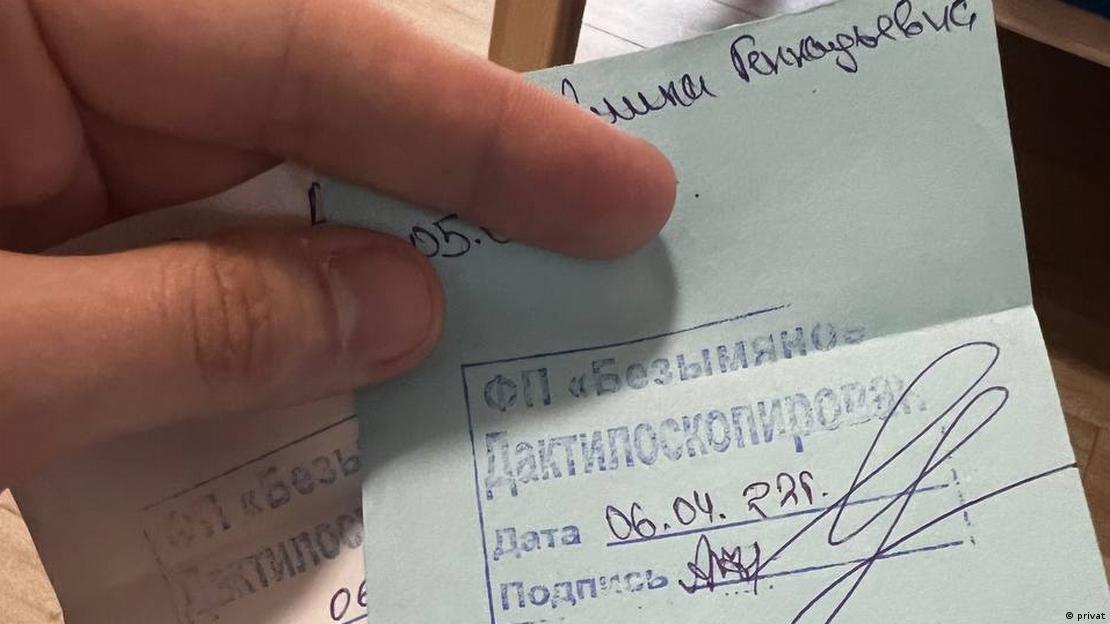

The filtration procedures began in the first half of March 2022 when the forced resettlement of Mariupol residents to Russia started. Thus, Rossiyskaya Gazeta, the official printed media of the Russian government, reported that 5,000 Ukrainians were detained in the Bezymyannoye camp and that they were being screened to prevent “Ukrainian nationalists disguised as refugees to avoid punishment” from entering Russia (cited from The Guardian). People leaving for Zaporizhzhia were also subjected to the same procedures.

The first stage of filtration

The filtration takes place in two stages. In the first stage, all refugees must pass document checks, fingerprinting, and initial questioning at so-called filtration points. This stage can last from several hours to several days, depending on the queue length at the filtration point. Much attention is paid to men, particularly those of draft age, who are questioned particularly thoroughly, sometimes with violence. The inspectors try to find out whether a person was earlier involved in the armed forces, law enforcement agencies, border guards, and other bodies of Ukrainian state power and local self-government and to ascertain their attitude to Ukraine and the war. Women are asked where their husbands are and whether they serve in the Ukrainian army. Everyone’s cell phone is examined for contacts with service members, pro-Ukrainian inscriptions, or ring melodies. Everyone has to undress, except for children and women over 45: inspectors look for tattoos indicating pro-Ukrainian orientation. They also look for specific chafes on the skin from wearing small arms and body armor, chafes on the index finger of the right hand, and bruises on the right shoulder from recoil during shooting. When people are suspected of disloyalty to Russia, they are detained and further held in custody, separating families, even mothers or fathers with children. There was a case when a father was separated from his three children who had been taken to Russia. Immediately after his release, he received a call from his eldest son that if he did not pick them up within three days, they would be adopted. The father immediately went to Russia and managed to pick up his children.

Filtration points were set up in large numbers wherever there were streams of refugees leaving the occupied territory. Filtration was also carried out at checkpoints.

People passing the first stage of filtration receive a small-sized certificate with the surname, first name and patronymic, date of birth, a stamp with the inscription “Dactyloscoped,” the name of the filtration point, the date and the signature of the person who performed the filtration. The surname of this person is not indicated. This “certificate” is a pass in all occupied territories. Having it, you can also enter the territory of the Russian Federation, and it must be presented at every check along with your passport. But even this certificate may not save you from the repeated procedure of checking your phone, luggage, body, etc.

The second stage of filtration

People detained at the first stage are sent under escort for further in-depth filtration during 30 days to filtration camps, deprivation of liberty places. Particularly stubborn Ukrainians were sometimes given a second term. Filtration camps are either former penitentiary institutions that have now been reopened or unofficial places of detention, where conditions are deplorable: overcrowding, inadequate food, often no access to water, lighting, toilets, fresh air, and no access to medical care.

There was a media report that Russian invaders were holding more than three thousand civilian residents of Mariupol in a “filtration prison” — the former penal colony No. 52 in the village of Olenivka in the Donetsk region. Another publication wrote, “This is where former law enforcers, pro-Ukrainian activists, and journalists are held. Now, it has become known about the second filtration prison in Olenivka based on the former Volnovakha penal colony No. 120”. Prisoners of war from the Azov regiment were also held in colony No. 120. On the night of July 28-29, 2022, there was an explosion here, which took the lives of 50 prisoners of war.

Below is the story of a former investigator Oleg, who worked in the Donetsk Regional Police Department.

On March 21, 2022, he tried to leave Mariupol in the direction of Zaporizhzhia. He was detained at the roadblock in Melekino village. According to him, former police employees were standing at the roadblock and pointing fingers at police officers they knew. There were also lists of Ukrainian civil servants at the checkpoints. Then, he was brought to Mangush to the district police department, where he spent 24 hours. There were more than 35 people in the premises where he was kept. He shared his cell with police officers, border guards, and rescuers from the State Emergency Service of Ukraine. A young woman from the penitentiary service was also detained. Then, he was sent under escort to Dokuchayevsk. The filtration point is located in the Palace of Culture in the center of Dokuchayevsk. Civilians have to visit it to obtain passes, while detainees are kept in the backyard of this building. Here, the detainees are sorted into several groups: military, police, other civil servants, and undocumented persons. They are held there for one day. Then, they are blindfolded and taken to Donetsk. On the premises of the former Department for Combating Organized Crime (5 Yungovskaya Street), they are placed in cells with 35—37 people in each. They are fingerprinted, photos of tattoos are taken, and their data is entered into the “Rubezh” and “Scorpion” databases. Here, they receive a suspect status. They are interrogated, especially about their interaction with Azov and Tornado military units, and their involvement in the investigation of offenses committed by persons who fought on the side of the DNR. Interrogators asked about the police archive location and the composition of the units and tried to induce cooperation.

After the interrogation, people are sent for medical examination while they wait for the convoy to prison. The examination was conducted in a friendly manner in the hospital where Oleg was checked. In another hospital (according to other people’s words), the doctor offered to shoot them without a medical examination.

After the medical examination, Oleg was sent to Donetsk pre-trial detention center. There, the protocol of administrative detention for 30 calendar days was drawn up on him based on a DNR internal normative act (Oleg can’t remember which one) on cooperation with terrorist organizations. After that, the detainees were brought to penal colony No. 120 near Volnovakha. They were kept by 35—40 people in the cells with dysfunctional toilets; water and food were not provided for several days. Then, the majority of the police officers were transferred to barrack huts. While staying in the barrack huts, they can go to the toilet in the street, and acquaintances can bring them food. They also repair these barrack huts themselves.

Oleg did not say anything about the interrogations in the colony. On May 8, he was released.

In filtration prisons, FSB (Russian Federal Security Service) officers participate in interrogations with the use of violence and various kinds of torture, having the same goal: to break a person and to extort a confession of loyalty to the Russian Federation. People passing this second stage of filtration were released after 30 days, received a certificate of filtration, and could go to Russia. Those who did not pass the second stage of filtration, who were not broken, received the status of prisoners of war according to the decree of the so-called State Defense Committee of the DNR #31 of April 26, 2022. They were sentenced to a 10-year prison term and sent to penal institutions in the Donetsk region. This wholly illegal and wild, even for Russians, decree was canceled after the “referendum” on the accession of the DNR to the Russian Federation at the end of September 2022, and some of the prisoners were released. It is unknown precisely how many of them were released and where the rest are. There is a version that they were transferred to Russian places of detention, where they were sentenced by Russian courts “for opposing a special military operation” (as they call this war in Russia); at least one such case is known.

We cannot specify the number of people put into filtration camps and those released from them; we do not have such data. Apparently, it is tens of thousands of people.

Assistance to prisoners of war, civil prisoners and their families

In 2024, KHPG paid a lot of attention to this category of war victims. Assistance to the families consisted of counselling them, tracing the whereabouts of prisoners and missing persons, and helping the prisoners themselves as much as possible. We worked in the Kharkiv, Kyiv, Chernihiv, Sumy, and Mykolaiv regions, although we also responded to inquiries from other regions.

Search for the location of prisoners of war, arrested civilians, missing persons is based on several types of evidentiary materials directly collected by KHPG. They include testimonial, documentary, and open-source information, as well as audiovisual content. The collected evidentiary materials are stored in two different databases: KHPG’s own database and T4P’s joint database administered by KHPG. In addition, the KHPG forms its own register of prisoners of war, civilian prisoners and missing persons, which also includes the data of the applicant — a family member who applied to the KHPG.

KHPG collects information using four methods: a) interview of victims (families of prisoners or missing persons) and witnesses; b) monitoring visits to the de-occupied territory; c) legal representation; d) open-source information.

KHPG conducts interviews with victims and witnesses of illegal detention or disappearances, interview families of prisoners of war, finding out all known information regarding detention, disappearance, capture and stay in captivity. KHPG identifies potential interviewees during its monitoring visits to the affected areas and through other forms of contact (e.g. phone, online meetings, drop-in office hours and through the KHPG missing persons hotline). During seven months, 227 trips were made to the affected areas.

KHPG lawyers provide legal aid to victims and represent them before national courts, the UN Human Rights Committee and other fora. Further to this, KHPG lawyers conduct atrocity crimes documentation work by collecting information on alleged international crimes for the purposes of criminal investigations and prosecutions at the ICC and other international accountability mechanisms. In the course of legal representation, KHPG lawyers cooperate with Ukrainian law enforcement agencies investigating and prosecuting international crimes, which allows them to obtain access to case files of the clients they represent, exchange information on incidents related to alleged international crimes and jointly visit crime scenes with the purpose of collecting information about such crimes.

KHPG collects and analyses open-source information of evidentiary value that can be used in criminal proceedings and for other accountability purposes. This information is of great importance for the search for the location of places of detention in which prisoners of war and civilian prisoners are held — 38 such places of detention were found in the Russian Federation and 14 in the temporarily occupied territory. The KHPG has at its disposal the surnames, first names and patronymics of 2,510 prisoners: military and civilians.

The registry contains data on 7,139 people (190 women, 6,710 men), including 2,294 prisoners of war, 841 missing civilians, 3,579 missing military personnel, and 188 missing children. 223 prisoners from among the missing recorded in the registry have been found. 130 prisoners convicted by Russian courts and courts in the temporarily occupied territory have also been found.