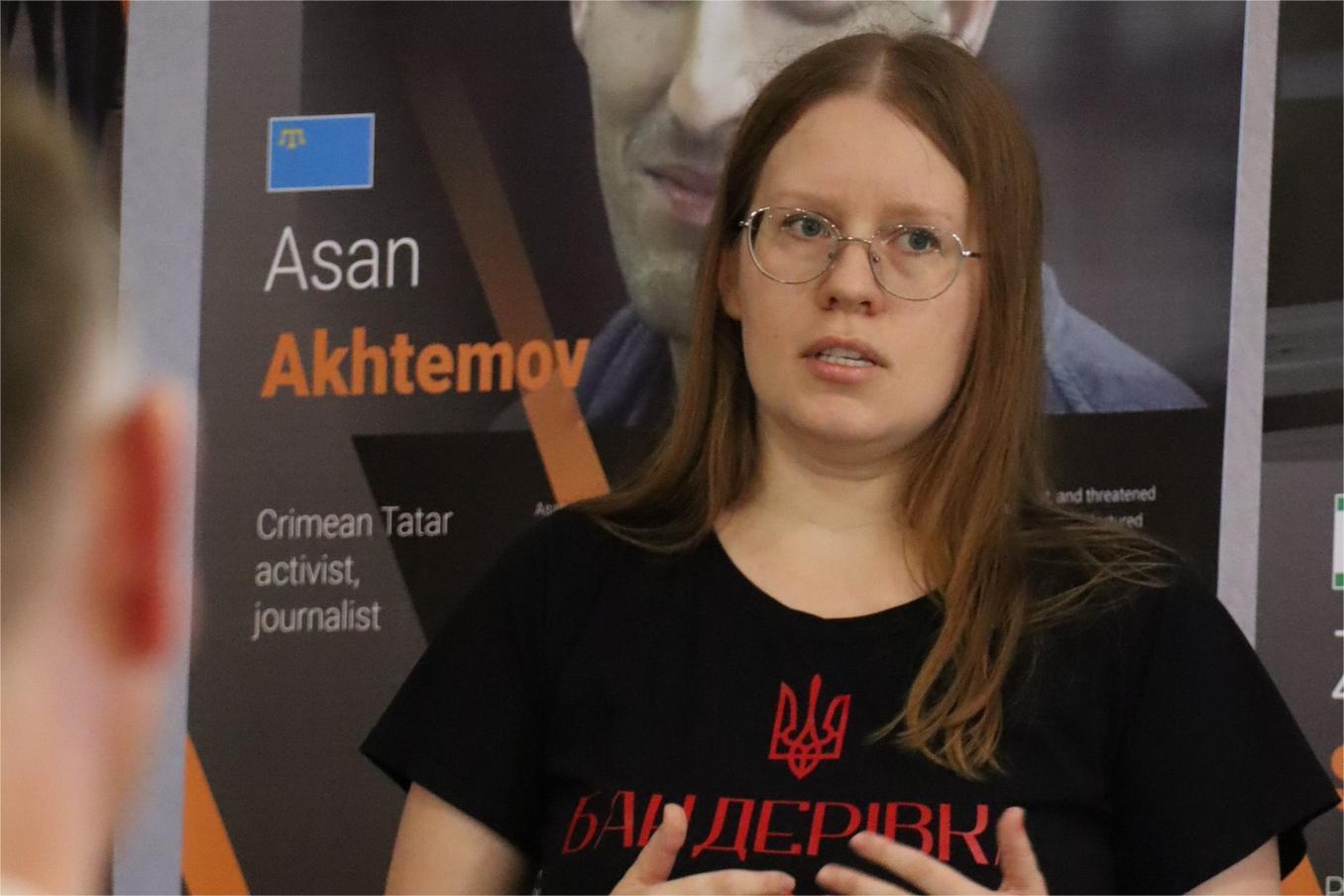

“I am an ethnic Ukrainian from Eastern Slobozhanshchyna,” — this is the first thing Nina says about herself when we meet. She doesn’t say “from Russia.” Although she holds Russian citizenship. For now. Nina is an asylum seeker in Ukraine.

Nina Belyaeva speaks and writes in Ukrainian. She was once interested in leftist ideology, but that’s in the past: the war and her study of history have completely changed her worldview. Now she is a co-founder of the “Eastern Slobozhanshchyna” and “Unity of Ukrainians from Historical Lands” movements, and one of the authors of the book “Involuntary Annexation: The History of the Liberation Struggle of Peoples Enslaved by Russia.” On the website of the Anti-Imperialist Bloc of Nations’ newsletter, she maintains a section on Ukrainians in the Russian Federation. She researches the criminal prosecution of ethnic Ukrainians in Russia.

Nina can spend hours discussing Ukrainianism during the time of the Ukrainian People’s Republic in her native Voronezh region. Instead, she has to talk about her ordeals with the Ukrainian migration services. Having arrived in Ukraine and successfully passed a thorough background check by the SBU, she is now trying to prove to the Migration Service in court that she poses no threat to our country.

And recently, a State Migration Service officer attempted to summon her to a bizarre meeting in the city. “I have reason to believe that the purpose of the meeting was to kidnap me and transport me to the Russian Federation through Belarus. Probably as part of an exchange under a false name”, — Nina says.

Escape

— When the full-scale invasion began, I was a local deputy in the Voronezh region. I saw the Ukrainian President’s address to Russian citizens. Ordinary Ukrainians were asking Russians to speak publicly. And I felt I couldn’t remain silent—I started writing on social media. When the situation began to be discussed in the deputy chat, I started pointing out to my colleagues the mendacity of Russian propaganda and the internal contradictions in their statements. At some point, I switched to Ukrainian—literally one sentence—and this provoked an even more negative reaction. They immediately wrote to me, “Well, now you’ve started speaking in your own language!” And four days later, at a meeting, the issue of my behavior was put on the agenda. I didn’t back down from my position; I spoke my mind—I called the actions of the Russian army in Ukraine a war crime. At the same meeting, the deputies voted to forward the materials about me to the prosecutor’s office.

At first, Nina thought it would end with an administrative case. But her lawyer warned her that she was facing criminal charges. She quickly packed up and left Russia. However, obtaining asylum in the EU proved nearly impossible.

— Russia first opened a case against me for fake news, and then two more cases for terrorism. As a lawyer, I’ve studied this issue. Currently, a person can be denied asylum in the European Union because Russia is prosecuting them under terrorism law. The person handling the case might not carefully examine the circumstances of their inclusion on the terrorist list and deny asylum on that basis. Essentially, I have to prove somehow that I’m not a terrorist. But to whom? You deal with the immigration service, but the security services decide whether you’re a terrorist or not. They might not even contact you during the decision-making process. This terrorist label in the EU is even worse than being accused of pedophilia.

Nina had to go to court in Latvia to prove she didn’t pose a threat to the European Union. Her asylum case dragged on, and the psychological uncertainty was weighing heavily on her. A friend mentioned the possibility of moving to Ukraine.

—They told me I could be useful to Ukraine and promised to help with my visa. I decided to withdraw from the EU asylum process because I saw my future in the country of my ethnic origin and didn’t want to waste time on the process in a place where I didn’t plan to live for long.

Nina was flying from Romania to Moldova, and from there she planned to go to Ukraine. However, she wasn’t allowed to enter Moldova. Again, because of the terrorism statute in Russia.

—I think they saw I was wanted. And they didn’t let me in without explanation; they returned me to the EU, to Romania. But since I had already withdrawn from the asylum process, I wasn’t allowed to stay in Romania either. I ended up at the airport. I have no visas, nothing, I’m on the international wanted list for terrorism. Romania wants to return me to Latvia. And Latvia, because I’ve already withdrawn from the asylum procedure, could send me to Turkey (which is where I entered the EU in 2022). And we’ve seen time and again how Turkey treats people like me: they simply put them on a plane and send them to Russia. So I merely fled Romania for Ukraine.

In Ukraine

Nina immediately applied for asylum to the Ukrainian border guards.

— They couldn’t register me. My appeal was rejected because they’re currently prohibited from doing so. Still, they looked up my information online and realized they couldn’t refuse me because I’m an ethnic Ukrainian, and I’m being persecuted because of my stance on Ukraine. We had an excellent conversation about the Ukrainian People’s Republic and its inclusion of the Voronezh and Kursk regions. Then I was handed over to the SBU, who conducted an investigation and released me to apply for asylum through the Migration Service. No one detained me. If I had posed any threat, the SBU would certainly not have let me go!

That was in May 2024. Since then, Nina has been trying to obtain asylum in Ukraine. She decided to approach the Migration Service with the support of the UN.

— I contacted the public organization “April 10”, a partner of the UNHCR. They reviewed my case and agreed to help. On August 12, 2024, I submitted an application to the SMS Office in the Odesa region. My application was registered at the registry office, but for some reason not at the Department for Protection Seekers. First, they replied that my documents had been sent to Kyiv, although they weren’t legally authorized to do so, as it wasn’t the responsibility of the SMS central office. That’s the responsibility of the regional offices. Kyiv responded that I could pose a threat to Ukraine’s security. So, the SBU checked me and decided I didn’t pose a threat, while the immigration officials have higher authority in this matter? The thing is, I provided them with all the documents I had. And then they saw the Latvian immigration officials’ decision that I posed a danger. Even though a Latvian court had long ago ruled that decision unlawful!

Nina had to go to court again, this time filing a lawsuit against the Ukrainian immigration officials. Representatives of the Security Service of Ukraine were summoned to court. They confirmed that they had no complaints or issues against Nina. The Odesa District Administrative Court upheld her demands. However, the migration service filed an appeal.

“The police will deal with you”

The appeal hearing date has not been set yet. While awaiting trial, Nina received a strange phone call. A man introduced himself in Russian as Yevhen, an employee of the Migration Service. He offered to meet anywhere in Odesa. Nina asked the official to speak Ukrainian, and he briefly switched to the official language. But a minute later, when a surprised Nina asked him to explain the reason and purpose of the meeting, Yevhen switched to Russian and began threatening to use law enforcement. For some reason, he even referred to the National Police of Ukraine as “Militsiya”: “Do you want me to bring you to our headquarters with the police? I can arrange that! Then we’ll communicate with you differently!”

This strange conversation took place on July 31st. This Yevhen (he actually turned out to be a State Migration Service employee) also called the “April 10” organization. However, he never explained why he wanted to meet with Nina, much less outside the institution.

Since then, she decided to await her trial in a safer location and, just in case, left Odessa.

— I think they simply wanted to kidnap me and, perhaps, put me on a bus under a false name for an exchange. Considering the activities I’m engaged in here, which are highly unpleasant to Russia... I spread historical truth. I’m one of the founders of the organization “Unity of Ukrainians from Historical Lands,” which not only protects ethnic Ukrainians with Russian citizenship but also helps locate abducted Ukrainian children and Ukrainian prisoners of war, and collects information on war criminals.

Nina, along with other members of the organization, exposes Russia’s ethnically motivated persecution of its own citizens of Ukrainian descent. She studies the forced Russification of the Eastern Slobozhanshchina region, which fell within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic during the Soviet era.

— In the Voronezh region, some schools offered Ukrainian language classes in the 1990s and 2000s, although this was only possible thanks to the efforts of volunteers. In Rossosh, a Ukrainian cultural festival was held until 2011. Russia destroyed all these movements by 2014. And when such institutions disappeared, the invasion of Ukraine began.

The situation with the migration service was highly stressful for Nina and had a negative impact on her health.

— When I learned that others were being detained, I realized there could be an order from Russia against me. Now I’m having panic attacks, sleep disturbances... I feel like I could be detained without reason if I go to the migration service. It’s genuinely emotionally devastating. You think this is your ethnic country, a democratic state, and then you get a call from someone who doesn’t even speak Ukrainian... I’m Ukrainian. I want to live in Ukraine.