My name is Yuriy Shapovalov. I have lived in Donetsk my whole life. Until 2014, I worked as a doctor at the regional hospital. I was researching the nervous system, working as a neurophysiologist at a diagnostic center.

When Russian aggression began in 2014, which they initially tried to pass off as an internal civil conflict, I continued to work at my hospital and, outside of work, headed a local cactus lovers’ club. I did not move to the territory under Ukrainian control. But everything happening in my hometown at the time was unacceptable to me.

I participated in pro-Ukrainian demonstrations in early 2014, and I immediately understood that this was not a local separatism-fueled conflict, but rather a somewhat covert act of Russian aggression. I saw everything with my own eyes.

I still worked at my hospital while managing a Twitter page to highlight the impact of the occupation on my city and the deterioration of residents’ lives. There were also posts about movements of military equipment and soldiers that I saw on the streets of my town.

I wrote about where I heard explosions or incoming shelling. All this led to my arrest by the authorities of the self-proclaimed “DPR”. In broad daylight, they knocked me to the ground, hit my cell phone out of my hands, twisted my arms behind my back with a plastic tie, put a bag over my head, and forced me into a car.

They took me to the MSS premises, the Ministry of State Security, as they called it, of the so-called “DPR”. It’s located near my hospital. And there, I probably went through the hardest hours, when they interrogated me with physical violence, that is, beatings.

I was questioned and beaten for several hours in a row. First, I was in one room, then in another. After that, interrogators moved me to a different floor, made me kneel in front of a table, and told me to rest my elbows on it. I had a bag over my head the entire time. The interrogation teams changed: first, some people came in, then others. They kept asking the same questions: who I worked for, who my supervisor was, and how much I was paid.

Beatings accompanied all of this. They hit me on the head and chest. In addition to the beatings, they were simulating an execution: putting a gun to the back of my head, clicking the trigger, and saying, “Oops, a misfire.” They also threatened to shoot me in the kneecap. And they kept beating me the whole time. That was the toughest part. Later, they made me sign some papers and took me home that same day. It was late at night, and my mother had already gone to sleep.

At home, they seized “material evidence”: took my laptop and tablet, changed all my passwords, and revoked access to my social networks and email. Later that day, they took me to “Izolyatsia.” This is a notorious prison, a former secret MSS detention site. A long time ago, it was a factory that produced insulation materials; after it closed, the premises became a cultural center where artists gathered. After 2014, the “DPR” authorities seized it and turned it into a secret prison — essentially a concentration camp. There, I was thrown into a basement cell.

It was a reasonably large room, roughly five by 10 meters, located in the basement. It appears to have been a former bomb shelter. There was no natural light, just a single dim electric light bulb, no water, no plumbing, and no sewage system. The exhaust fan hummed constantly; it was very cold. It was January, and there was no heating. We didn’t sleep on separate bunks; we slept on a solid platform with mattresses laid out side by side. We were always under video surveillance. During the day, we weren’t allowed to lie on the mattresses — only sit or stand. We were also required to march in sync and sing the song “Vstavay, strana ogromnaya” (“Arise, Great Country”—a Soviet patriotic song from WWII).

They brought us water in a 50-liter plastic barrel, and we had a plastic bottle with a hole in the cap to use this water for all our needs. Thus, using this bottle, we washed ourselves, brushed our teeth, and rinsed our socks over an old plastic paint pail. Those were the terms of our detention.

We used a plastic container to relieve ourselves, which I believe was from a bio-toilet. There was a seat on top of it. When this container was full, we had to carry it out into the yard by hand, through a steep staircase, and pour it into a sewer hatch.

When I got into the cell, I immediately felt that I might have broken ribs. My cellmates suggested bandaging them immediately. At first, I thought it was unnecessary and refused, but a day or two later, as muscle protection lessened, I heard the crunch of bone fragments and realized my ribs were indeed fractured. Then the guys found an old T-shirt, tied it around my chest, and I walked around bandaged like that for several weeks.

When I finally took off my pants and looked at my legs, I was horrified. They were completely black all over, with their outer surface looking thoroughly bruised. Then the bruises on my left leg disappeared on their own, but the ones on the right proved more stubborn. I believed it was most likely thrombophlebitis because my leg was swollen and puffy. But it also went away on its own, without any treatment. In “Izolyatsia,” I spent exactly 100 days.

During this time, operatives from the so-called MSS came to see me once, and several times they took me by car to the MSS premises for interrogation. At these interrogations, physical force was also used, though not as intensely as on the first day.

There was another episode: when they demanded that I sign something I disagreed with, they put a plastic bag over my head and tightened it around my neck. When I started to suffocate, I said, “All right, I’ll sign whatever you want.”

They accused me of spying for Ukraine. However, when the case was transferred to the prosecutor’s office, it was returned, stating that one article was insufficient. Then they reopened the case for three days and added “attempted espionage” as a charge to the original espionage charge. An extraordinary combination. Under one article, the prosecutor requested 12 years’ imprisonment, and under the other, 10 years. When he added them up, it came to 14 years, but the judge “took pity” and sentenced me to 13 years in a strict-regime penal colony.

Two months later, around June 16 or 17, I was transferred from the Donetsk pretrial detention center to the Makiyivka colony, where I remained until my release.

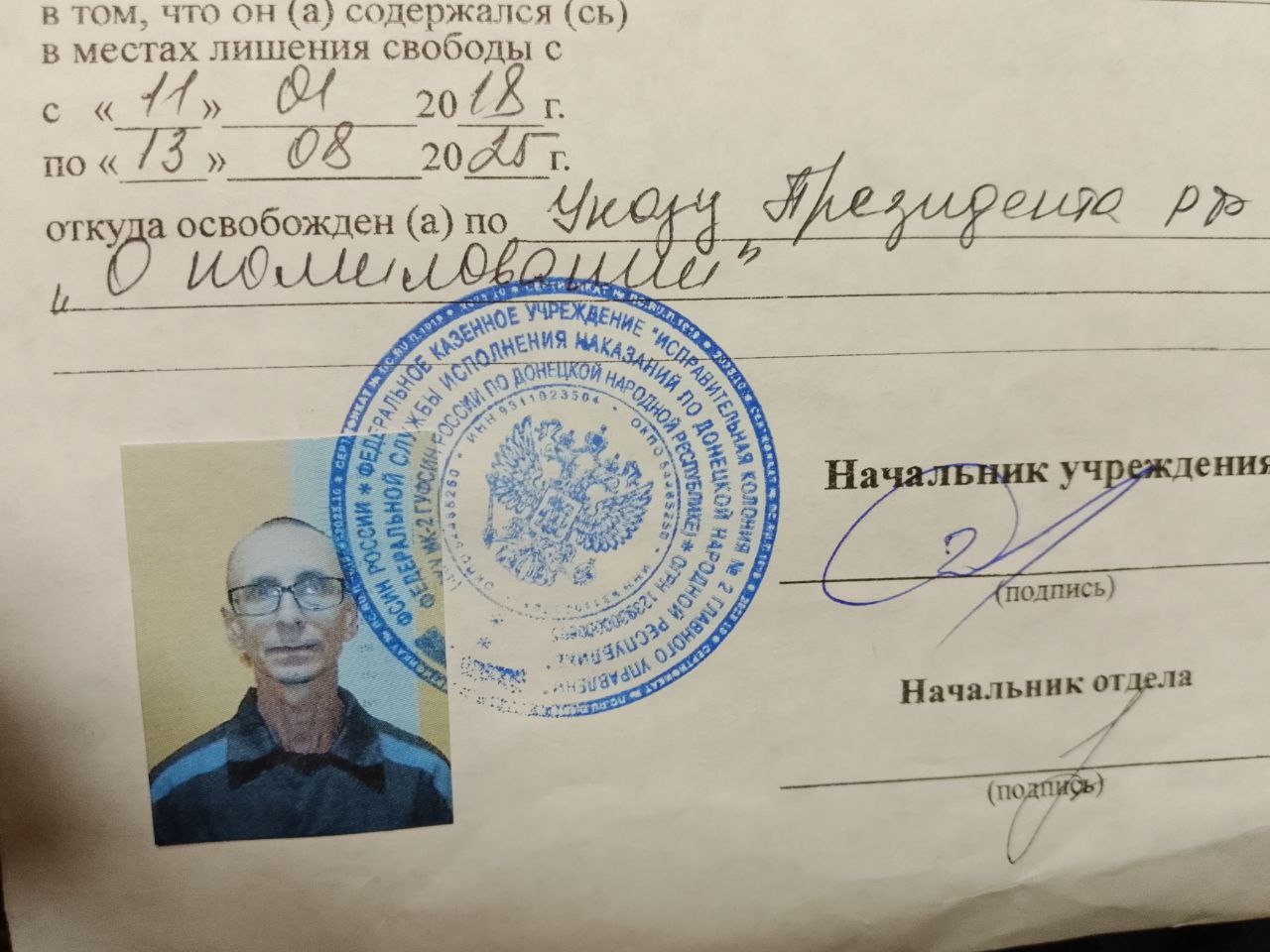

The release was unexpected for us. We were told about the exchange on the day we were taken away. It was during the morning check, held every day at 9 a.m. They read the list aloud. They gave us about half an hour to pack our things, transferred us to another, empty barrack, where we were photographed and searched.

Then they loaded us into a paddy wagon and took us to Rostov. There, at some military airfield, they put us on a plane. The boarding procedure was also rather tough. They taped our eyes shut. Our hands were bound behind our backs with plastic ties. I must have angered the guard who was doing this. He said, “Take off your glasses and put them in the bag.” I replied, “I’d rather put them in my pocket,” and looked at him. He was pretty talkative. But he shouted, “Don’t look!” and tightened the ties around my hands as much as he could. I immediately felt my hands go numb, and then they began to feel like they were on fire.

The plane landed at an airfield. Someone said it might have been near Moscow. I don’t know. They took us off the plane and into a spacious room, a hangar. And there we stood all night beside our bags. We were not allowed to sit or lie down. We were not given anything to eat or drink. When people asked to use the toilet, they were initially denied access. Then our guards began taking 10 people at a time out to relieve themselves.

We heard other planes landing at the airport. They likely arrived from different parts of Russia. Everyone who had to be exchanged was brought there. We stayed there until morning. That room was freezing.

In the morning, we were loaded onto another, larger plane. At least there were benches where we could sit. This plane took us to Gomel, Belarus. All this time, our eyes and hands remained taped. Our guards removed the tape only before we left the aircraft in Gomel. Belarusian buses were already waiting for us with regular supplies of food and water.

These buses took us directly to the exchange point on the border. There, we finally heard Ukrainian, saw Ukrainian flags, and people from the Coordination Headquarters came in to greet us. It marked the start of a new life. Then we felt that this was truly the end of our ordeal — a moment of true liberation.

It was very moving. Then, on the way to Chernihiv, people greeted us along the road: they just came out with Ukrainian flags. We felt it very emotionally. That’s how the exchange went down.

I would definitely like to note that only part of the prisoners from our penal colony were liberated. There are still people there who have been imprisoned since 2018 and 2017. There is even a guy who has been detained since 2015.

Some of those who remained told me they had lived through the 2019 exchange: then, almost everyone was taken away, leaving a few behind. They said it was a shocking experience for them and very hard to go through. And now some of the guys had to go through the same experience again: we were taken away, while they were left behind. I can still see their faces.

There are various guys there. Some of them are true patriots, pro-Ukrainian people who must be brought back home. I feel very sorry for the guys who stayed there, though, of course, they are very diverse. They must be freed — by any means necessary.