Russia’s FSB has, for the first time, applied new legislation enabling prosecution for merely looking something up on the Internet. The 20-year-old student was detained just hours after he looked up the relevant information, linked with Ukraine’s defenders. Given the small amount of time and the fact that the FSB detained him before looking at his phone, it seems chillingly likely that it was his mobile phone provider (T2) who reported him to the FSB. The company has, apparently, denied this, but the young man’s lawyer, while stressing that he has no hard proof, is clearly unconvinced.

Although news of the arrest only emerged after a court hearing on 6 November 2025, Sergei Glukhikh, from Kamensk-Uralsk (Sverdlov oblast) was detained after he accessed the ‘prohibited content’ on 24 September. According to his lawyer Sergei Barsukov, the 20-year-old medical college student was looking at the Internet while on a bus and saw some images with the symbols of the Azov Regiment (part of Ukraine’s Armed Forces) and of the Russian Volunteer Corps, which is fighting on Ukraine’s side. He read the material and left the website, Barsukov says.

Glukhikh was detained by the FSB that same evening. He was released after admitting to the FSB’s charges. The ‘case material’ was, however, passed to the police who drew up administrative charges under Article 13.53 of Russia’s code of administrative offences. This imposes liability for so-called “searches for knowingly extremist material”, as well as for gaining access to these, including through the use of VPNs or other means of accessing resources where access has been restricted. At the first hearing on 14 October before a magistrate, the defence asked for the two FSB officers who took ‘an explanation’ from Glukhikh to be called as witnesses. These two failed to appear at the second hearing on 6 November. During this same hearing, Barsukov insisted that his client had not had the intention of accessing ‘extremist literature’, with this required by the new ‘offence’. The magistrate agreed and sent the case material back to the police.

Barsukov is generally scathing about the case material. Not only is intent not proven, as required, but the entire ‘case’ hinges on two screenshots and the notes made by the FSB who, he says, put psychological pressure on Glukhikh.

That, however, does not at all guarantee that the case will not be returned to the magistrate, and result in Glukhich’s conviction. It is, for example, noteworthy that Baza, a Telegram channel with links to the FSB, posted a ‘report’ on the prosecution, with several telling distortions, mainly aimed at exaggerating the young man’s ‘guilt’. According to Barsukov, the photo produced was not of Glukhikh, nor is it true that there were over 30 links to the Azov Regiment, to the Russian Volunteer Corps and also to UNA-UNSO (the Ukrainian National Assembly – Ukrainian People’s Self-Defence). There would, in other circumstances, be a lot to say about UNO-UNSO, but here it was a red herring, aimed at blurring the fact that Glukhikh was accused of trying to find out, through brief Internet searches, about two formations which only Russia is claiming to be ‘terrorist’ – namely the Azov Regiment and the Russian Volunteer Corps. The Russian supreme court’s ruling on 2 August 2022, outlawing the Azov Regiment as ‘terrorist’, was widely condemned as a ploy to justify the persecution of Ukrainian defenders of Mariupol, many of whom were serving in the Azov Regiment. Despite the fact that Azov is part of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, and that the vast majority of defenders of Mariupol were taken captive long before the ruling, Russia has, indeed, used the supreme court ruling as excuse to stage show trials and pass huge sentences against Ukrainian prisoners of war.

Barsukov stresses that the case material does not state how the FSB came by their information.

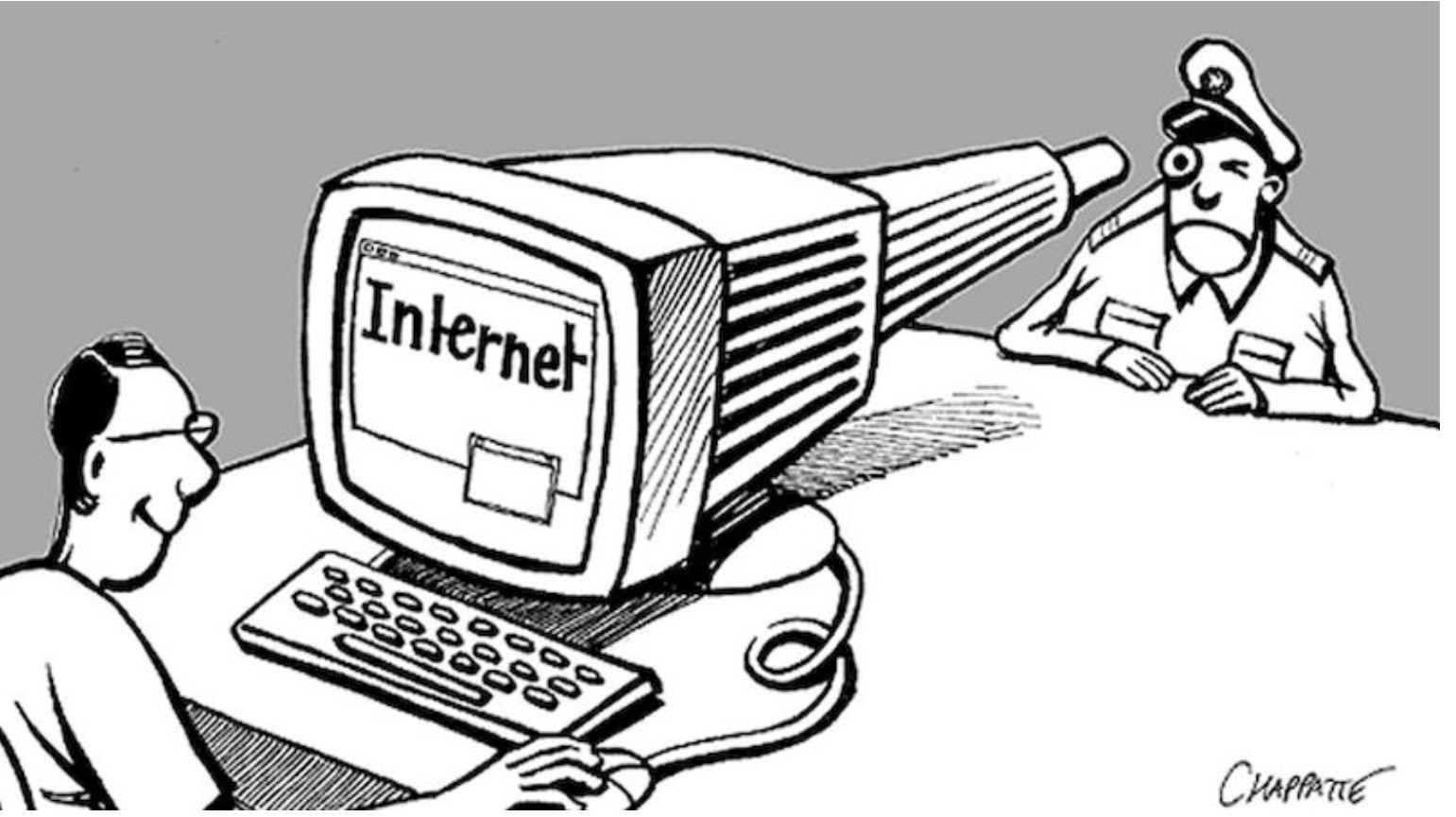

It may well be that this is deliberate, with one of the reasons for such prosecutions being the chilling message they send others and the impression that the FSB has everybody under close surveillance.

Russia’s State Duma rushed through the relevant legislative amendments on 17 July 2025 with Russian leader Vladimir Putin just as quick to sign them into force. The amendments, which came into effect on 1 September, impose serious fines for using VPNs to access ‘prohibited sites’ and modest fines for what are termed ‘searches for knowingly extremist material’. These are, purportedly, only to be applied if this was “a deliberate search”, although how that is defined seems at least as loose as what is meant by ‘extremist material’. This is particularly true with respect to occupied parts of Ukraine, where essentially anything linked with Ukrainian culture, history and / or identity can end up labelled. Such woolly terminology is quite deliberate. The fluid interpretation and ever-growing list of banned material instil terror and make it much more likely that people will engage in self-censorship, avoiding sites ‘just in case’.

See also: