‘The helicopter skimmed the treetops.’ Azov fighter tells of his evacuation from Mariupol.

In an interview, Vladyslav told KHPG about the wound he received while defending Azovstal, the violent battles in Mariupol and his night-time evacuation by helicopter.

A veteran of the 2014-2015 Russian-Ukrainian war, Vladyslav volunteered to fight on 25 February and was sent to join the Azov special unit in Mariupol. At his request we are not revealing his full name, nom de guerre or other personal information.

“The fighting was intense in Mariupol from the first days of the invasion, ”Vladyslav told us: “but none of the Azov fighters were worried,their morale was high.”

The Russian army was bombarding the city with all kinds of explosives. The left bank of the Kalmius River that divides Mariupol suffered the most. The Russians also hit the Azov unit but, as Vladyslav says, their intention was to destroy the city rather than individual military targets.

“They hit our unit, but we were not the target. They wanted to level the city. Just imagine, a 16-storey building on fire with people screaming inside. It was madness, and incomparable with 2014.”

According to Vladyslav, the Russians used foot-soldiers of the Donetsk and Luhansk “People’s Republics” as cannon fodder, sending them into battle first. “An observer identified where we were shooting from and then a tank or a mortar arrived, and they started pounding us.”

The KHPG database records half a dozen cases of forced mobilization, which is classified under international law as a war crime.

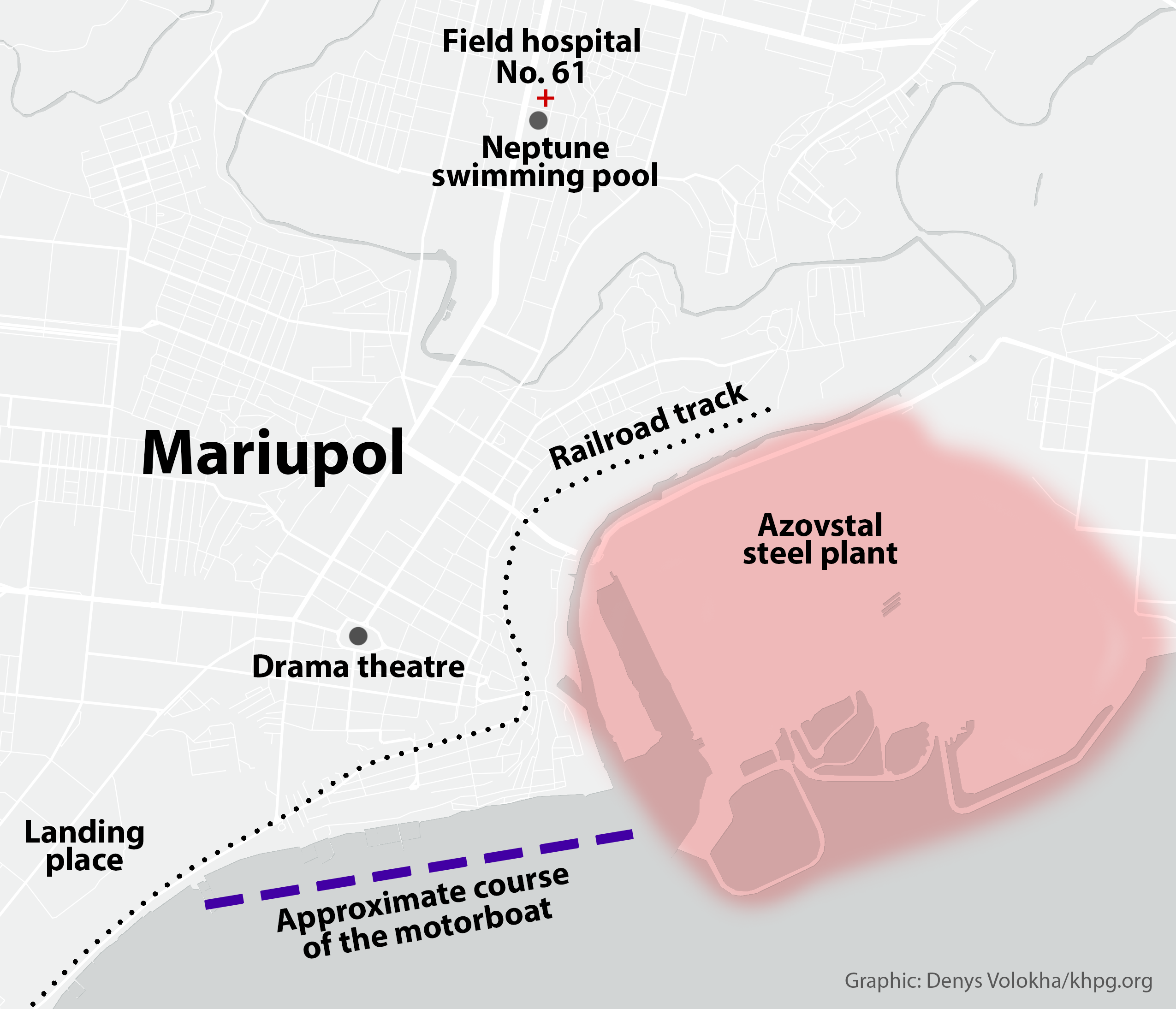

On 13 March Vladyslav was wounded. He then spent three days at a hospital near the “Neptune” indoor swimming pool (probably the 61st mobile military hospital).

“We were already in the Azovstal plant. Some of our boys said that the Russians had broken through — two armoured personnel carriers (APCs) and an infantry truck,” says Vladyslav. “We moved out and defended ourselves from all sides. I heard a drone overhead. I wanted to shoot it down, but the lads told me that it was one of ours. Then the mortar went off. The boys said, it was pounding the APC. The hell it was! It was pounding me.”

Vladyslav was injured when a mine blew up. It was necessary to amputate his heel bone. After the wound healed, he was supposed to spend three or four months in rehabilitation. But Vladyslav spent only three days in hospital: on 16 March it was hit by a missile. He and other wounded patients were evacuated to the bomb shelter beneath Azovstal.

“The missile hit the surgery unit and penetrated the ground floor. I didn’t go there much because of my temporary limitations [laughs]. Two or three of our surgeons and nurses were there, performing operations. A few guys lay on the operating tables: they died when the respirators failed.”

The fighting was fierce around Azovstal; many were killed or wounded. Although the shelter was three floors below ground, some of the bombs dropped by the Russians made the walls shake, even there.

The fighters were fed once a day. In late March the supply of bandages began to run out, and the wounded could not have their bandages changed often enough. “And when your leg falls asleep and you do not change the bandages, no painkillers can help,” adds Vladyslav.

Evacuation from a besieged city

On the night of 31 March and 1 April the wounded in the Azovstal shelter were told to pack their things. Vladyslav was among them. Now Ukrainian forces have left the plant, he can describe the evacuation.

“At night we climbed into trucks; there were three groups of 15 people each. We followed different routes and were drivento somewhere on the coast.15 people boarded the same motorboat — there was barely room for us all. We swam 15-20 minutes [to reach it]. We left the boat wet and began waiting for the others. And all this was happening not far from the Russians. Then [our guides] said: ‘Boys, we need to walk another 800 metres.’ I said: ‘I can’t make it.’”

“I stumbled about 200 metres. We had to walk by the sea. There was a railway embankment with fist-sized stones. It was night and, of course, I could not turn on the flashlight. I fell over. One guy held out his assault rifle, I grabbed his neck and he pulled me another 500 or 600 metres. We fell two more times.”

After that the fighters were brought in trucks to the sanatorium, where they were boarded buses. Vladyslav and three or four others were “loaded” into the back of a Mitsubishi pickup (L-200).

“We were the first, and the engine stopped dead on the [railway] crossing. Those f***** began tossing mines at us, and still the car wouldn’t start. Two buses overtook us.‘Well, that’s it,’ I thought.”

After a while, the engine started and they reached their destination. Four Mi-8 helicopters were waiting for them. Vladyslav boarded the third.

“First, we flew over the seashore. I thought we were going to plunge into the sea — we were flying a few metres above the waves. As soon as we set out across the water, I heard the helicopter began to vibrate. I started praying,” recalls Vladyslav.

The Russians were still firing but three Ukrainian helicopters successfully reached Dnipro, flying at a minimum altitude. The second helicopter to depart was forced to land because its engine malfunctioned. The Russians must have destroyed it after that emergency landing. One blade of Vladyslav’s helicopter was damaged by enemy fire.

“The helicopter flew over the fields. Then, to fly around some woods it rose several metres in the air and still its chassis touched the treetops. That is how low we flew.”

In Dnipro the pilot of the Mi-8 told his passengers: “Today was your second birthday.”

“Boy. If only you knew how many such moments I have had. And how many times I was born again!” Vladyslav recalls mockingly. In the 2014-2015 war he fought in the Kulchitsky battalion.

According to Vladyslav, the pilots were at risk of not returning from Mariupol. Yet only two helicopters were shot down during the evacuation from Azovstal: one on the night of 1 April, the other during the next evacuation, which was the last.

During that last evacuation, Vladyslav adds, the helicopters flew straight to the Azovstal plant.

President Zelensky has said that “90% of pilots” never made it back from trips to the besieged city of Mariupol. In an interview Azov commander Andriy Biletsky said there were over five attempts to breakthrough by air, delivering reinforcements and evacuating the wounded: two of those attempts were unsuccessful, he said.

“I don’t know what I would have done if I had not been evacuated,” adds Vladyslav. “I wasn’t going to be taken alive. I had a razor good and ready.”

Translation by John Crowfoot.