A resident of Mariupol, Olga says that each day people died nearby when they went outside to prepare food on open fires. When she first heard the explosions on 24 February, she told her son it was thunder. Later she could not stop crying when she realized what was going on.

What did you do in Mariupol before the war?

I worked at a beauty salon. I was also studying for my second degree: it was my dream to become a lawyer. I was then in my fourth year at the Yaroslav the Wise College. This summer I was due to work as a junior lawyer.

What happened on 24 February 2022? And next?

That Thursday between 4 and 5 pm we were woken by several explosions. Usually no sound disturbs my son, and you can’t wake him up. This was so loud that he called from his room: “Mom, what was that?” Don’t worry, I told him, it was just thunder.

I went online to find out what was going on: war had begun. We heard explosions throughout the day on 24 February. Most residents of Mariupol believed that things would be limited [as in 2015] to the outskirts of the city. I did not expect such a nightmare. Teachers said children could stay at home. I went out to buy food, and already the shelves were almost empty. I bought the basics, the food we usually buy.

In a day or so, around 25-26 February, I realized there wouldn’t be enough to eat. Panic mounted: we had to buy more. My son and I left our block of flats.The ATB food store was already closed: it was empty and had nothing to sell. We wanted to go further, but a shell hit the boarding school not far from home. We were outside at that moment, and the ground was shaking.

Each day the shelling grew more intense. On 24 February I was not afraid to go and buy food; by 26 February we ran home like hell as soon as it started. The bombing was very loud. I felt as though it flew, whistling, over our heads. We stayed put after that.

You first told your boy it was thunder. What about later?

Later I began to explain, to stop him worrying. I didn’t use words that might scare him – I didn’t say it was war, I simply said there would be some noise and he shouldn’t worry. We avoided the topic.

Afterwards it became impossible to ignore because the bombing was very intense. I explained everything to him. Russia had attacked us, I said, and is waging war on Ukraine. My son is ten years old, he understood.

When did the first difficulties with water and electricity begin?

From 24 to 28 February my son and I were on our own in the apartment. On 1 March, the telephone was still working. My father called and said that a building next to their house had been hit by a Grad missile. The building burned to the ground in minutes. It didn’t even burn, really – one moment it was hit, the next it had vanished. My parents panicked, grabbed the first bags they could find and rushed to join us. They would spend several days at my place, they thought, and then return home.

On 1 March, a massive attack began. Until then we slept in our own beds: now we had to sleep on the floor. I can see the Rankovy Market from our windows, and during that night it was hit by a shell. A fire started and we could not get back to sleep, because the bombs kept falling. The telephone still worked, however, and so did the water supply. The pressure was not as good as before, so we filled the bathtub with water and all the containers we could find.

On 2 March about 12:30 am a shell struck our building. It did not hit my apartment, thank God, but the third block of flats (I live in the second block). The missile hit the asphalt near the stairwell entrance. Some part of it broke off and smashed through the windows on the ground floor, starting a fire. There was no water to put it out since supplies were running low. The first three floors of the building next to ours were on fire. We tried calling the firefighters; we did not yet realize that they couldn’t reach us. Somehow (I don’t know how) people managed to put out the fire. They entered the burning apartments and pulled down curtains that had begun to melt.

We were still able to call my husband in Kyiv. I warned him that a shell had fallen near us, but we were alive and okay. From 2 March we all started sleeping in the hallway – my child and I, my parents and our neighbors who also had a young family (a man, a child, and a pregnant woman). We all hid in that small, shared corridor.

The light and the internet disappeared after 2 March. The fifth and sixth blocks of our building still had gas. We ran over there to cook food or boil some water. Several days later the gas supply also vanished. We lived without a phone or the internet, not knowing what was going on.

Many were convinced it would all soon be over. The fighting would last a fortnight, people thought: we just had to sit and wait. But time passed, nothing changed, and the bombs kept falling. People began going outside to light fires to cook on. It was very dangerous – it’s terrifying to recall it now. Every day someone died by an open fire, because of the constant shelling. The bombardment seemed wholly unpredictable. Later we realized there was often a pause in the bombing between 10 and 11 am: we could go out then. Such calculations were very unreliable. The guys kept fires going in the courtyard, and we would dash out to cook something. You couldn’t stay long.Throw some rice in a pan, add water, and wait until it was half ready.

We slept in the hallway from 2 to 6 March. Our neighbors had relatives in the bomb shelter under the sweet factory: it had a good shelter equipped with strong doors, and gas masks were available. Our neighbors wanted to go there, even on foot, but because of the shelling they dared not risk it. Somehow, they got in touch with their relatives. On 6 March we had just settled down for the night in the hall when someone knocked at the door. We were terrified. Do not to open your door to anyone, we’d been warned. Two police officers stood there. They had come to pick up the neighbors: “Pack your things,” they said, “and we’ll take you to your relatives.” What about us, we asked. “If you want,” said one of them, “we can take you as well.” We were afraid to leave the building but, thank the Lord, the policeman explained that sleeping in the hallway was dangerous. No building had yet been so damaged that the basement was affected. Some apartments were hit, people died in hallways, too.

As long as the neighbors were with us, we felt calmer. We were all together. After they left, we decided not to stay in the hallway. They drove off to join their relatives about 11 pm. We took warm blankets, mattresses – everything we had– and went down to the basement. After 6 March that’s where we slept.

It was also warmer down in the basement. March was very cold this year: minus 12-15 Centigrade. The hallway was drafty, and it was bitterly cold. The basement, to our surprise, was warmer because many people were already there. It was also very dusty. Our first night in the basement we both started crying. There was no way we could survive, I thought then. Each day was worse than before. At first, we slept in our apartment, then in the hallway outside; finally we ended up in the basement with a lot of other people and terrible dust everywhere. I breathed in and my nose and lungs were full of dust: it was unbearable. I felt an indescribable sense of despair.

We returned occasionally to our apartment when things were quieter. We used the toilet; we washed in what water was left in the bathtub; and we rinsed the dust from our noses. We were only there a short while, and we stayed in the hallway. I have some history books. Grandpa Svyryd, now a popular author, writes very well about the history of Ukraine. My mom read to us from that history book and the neighbors gathered round; it helped pass the time. Once the shelling again grew intense, we rushed down to the basement, closed the door and waited.

It was quiet there. I sat and thought, “Perhaps the war has ended?” Then I’d go outside and confront all the horrors.

How was the basement equipped?

It’s not a bomb shelter. There are wires and pipes there, and other stuff. Plain concrete walls and the floor was no more than trampled earth. With everyone moving around dust from the floor rose into the air. There were no mice or rats, but people were not intended to live there. It was a long and narrow corridor with rooms to left and right.

Can you recall a cheerful moment from your life in the basement?

The first night when my child and I moved there and cried in desperation, some women passed us, a mother and two daughters. They were handing out cookies and candy to the children. I was surprised: they simply approached us and gave my child a bag of sweets – we didn’t have any sweets then. We hung on to that little bag and ate the sweets untilwe reached safety. It raised our spirits and we stopped crying.

My husband and I owned a huge candle. We have been married for 12 years and never once lit it. Now we played Lotto with the neighbors by the light of that candle. It was decorative and not very bright, but the basement was pitch black and the candle helped us see a little.

The scariest memory was on 2 March when a shell hit our building. I don’t remember dates after that. No one in the building knew what the date was, or the day of the week. Everyone knew how long the war had been going on. Every day someone from our courtyard died.

People cooked on the fire between my block of flats and the next. A shell fell there and killed a man. Our acquaintances in the next building slept in the basement all the time: one night they decided to sleep in their apartment. They lived on the ninth floor, and a shell hit them. The father covered his wife and child with his body and was killed. Each day we received horrifying news about our neighbors and the people who lived in the same building. Since the ground was frozen, we only buried them to begin with; later their bodies were simply left lying around.

We ran to our friends in the sixth block for help. Denys had a minibus and took the wounded to hospital despite the shelling. “How can he be so brave?” we wondered. He refused no one: he leapt into the vehicle and off he went.

When did the planes come with the first bombs?

The planes appeared in early March. We heard various explosions. Most likely, it started on 2 March, all those horrible sounds. As a woman, I don’t know much about it, but there were many different kinds of noise, a variety of artillery shells were going off. After a while we could tell whether they were ours or theirs. If they flew past, we’d risk approaching the fires again.

When did you first see soldiers from Russia or the Donetsk “People’s Republic” (DPR)? How did they behave? What did they say?

About 13-14 March two soldiers came running towards our building. I don’t know whether they were from the DPR or from Russia. They dashed into the sixth stairwell entrance and hid behind the doors. Our godparents live there, our friends, and they were surprised by the soldiers’ appearance – dirty and savage. “Please leave,” people started shouting, “there are children here!” “Stop that noise,” they replied, “We’ll soon be gone.” Some of our bottles of drinking water stood on the ground floor. They drank the water defiantly, threw the bottles away and ran off.

We heard rumors that around 10 March DPR fighters were already at No 60, a neighboring building. They forced people out of their apartments and drew up lists of those willing to leave. Back then nobody imagined you could put down your name [for evacuation], it was only a rumor.

Our friends live on the first floor. The night we left, 16-17 March, they stayed in the apartment and heard a discussion outside. They looked out and saw Kadyrov’s Chechen fighters, with their “Allahu Akbar!” and bearded faces. They were standing near their windows, and before 15 March they were already on our street.

How did you learn you could get out of the city? How did you leave?

Between 5 and 10 March there was no telephone link at all, and I couldn’t contact my husband in Kyiv to let him know we were alive and well. Around 9-10 March the cellphone operator Kyivstar restored the signal. If we stood and waited in certain places, we could send and receive messages. As soon as I heard from my husband, I started texting him periodically.

About 11-12 March he began talking about evacuation corridors. People responded to the call for the first corridor. Those willing to leave should assemble, it was said, near the Drama Theater. People from our building went and, thank God, they returned alive and well. Nobody was waiting by the Drama Theater, they told us, and there were no other corridors. I don’t know which side started that rumor, Russia or Ukraine. We did not believe it at first. When our neighbors returned, they said the mobile phone signal was better in the city center: they had been in touch with their relatives. The embankment was intact, they drove along it, and said it was fine. The nightly curfew began at 4 or 5 pm so they spent the night in the center of Mariupol. They returned in a bad mood because they had wasted their gasoline and punctured a tire. By then gasoline was worth its weight in gold. We waited for the chance to leave, starting up the generators and using them to charge our phones.

Then my husband began writing that some people had got out. He told us of the routes his acquaintances had used to leave Mariupol. From 14 March onwards we made plans to leave the city. Our first attempt was on 15 March. With our neighbors we put together a convoy of vehicles. That day, however, the shelling never stopped from the moment we woke up, not even for a minute. It was scary and none of the neighbors would risk it. A friend left with her family that day, from the Left Bank district [eastern bank of the Kalmius River] and their vehicle was hit. Her husband died and she and her daughter were injured. The daughter received a neck wound, her mom was shot in the back. The 15-year-old girl went to hospital on foot, then her mother was driven there.

We tried again the next day. My husband texted that his acquaintance had left by going west through Mukhyne. Our friend who arranged the convoy got on his bike and went to scout out Leporsky Street and the Embankment. He studied all possible routes. He did not reach Mukhyne: Do not even try, he was told, it’s impossible to get out that way. On his return he started crying: ”There’s no way out of the Left Bank district,” he said. Everything was broken, blocked and full of mines. This grown man was so desperate that he sat and wept.

Then my husband messaged me again. It was fine, he wrote, we could get out through Mukhyne. On 16 March we gathered together everyone willing to go and prayed for a quiet day. The following day our convoy did leave via Mukhyne. There were two huge trucks, Kraz or Kamaz, blocking the way when we got there and the gap between them was narrow. A small car passed us, and its occupants tried bending its bumpers to squeeze through. Our friends had a minivan. They spent a long while struggling to pass the two trucks and put a lot of dents in their vehicle. We agreed we would never leave one another behind. The first small cars passed while we stood in our convoy and waited our turn.

We left the city at 8 am that day. It was very quiet. It took us half an hour to reach Mukhyne. We drove through and then waited for the others to arrive. At that moment, Grad shells started raining down. Ilychivsky district lay ahead of us. We saw something catch fire there. If we were hit everybody prayed to die instantly. It was very scary. Our friends squeezed through. They dented their car, but that didn’t matter. We drove through the Illichivsky district. We were told the route we must follow. We could not wander off it because there were mines everywhere. We followed orders to the letter. It was the first day we had left the basement and could see what had happened to our city. We knew the shells were falling somewhere, but I couldn’thave foreseen the extent of the destruction. And it all happened so quickly!

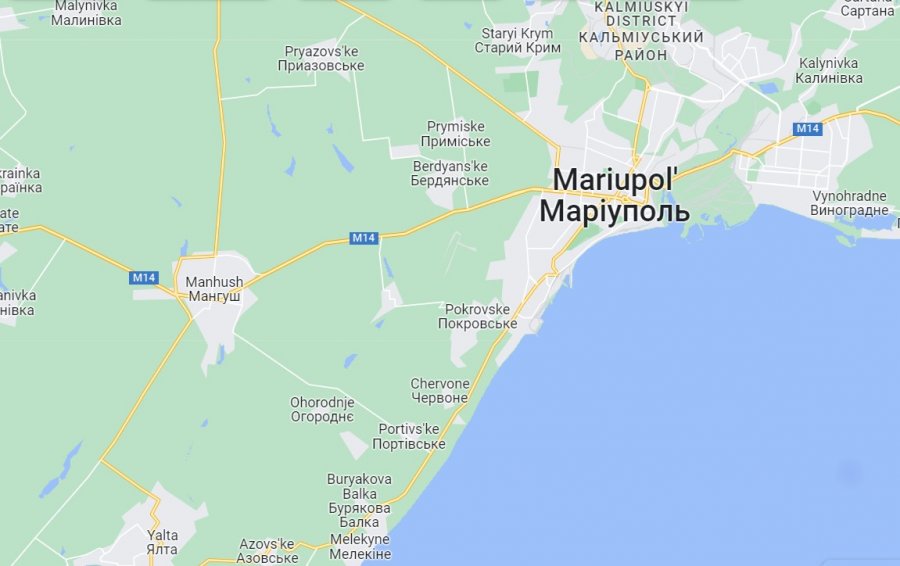

Bodies lay everywhere, out on the sidewalks. There were many burned-out vehicles, ruined buildings and stores. Nothing was intact, there was not a single undamaged building. We could not see the road because of the rubble. It was scary to drive because we did not know what was mined. We followed the route because someone had driven there before and said it was safe. Between the Left Bank district and the [A14] road to Manhush I think I never stopped holding my breath. I was afraid to inhale; the situation was very tense. Yet many people left then, and the convoy was quite large. We stood for a long time in gridlock at the Melekine checkpoint.

Were DPR fighters there already?

Yes, yes! Few people were leaving the Left Bank district because they believed they were cut off. They thought their only chance was to head east [to territory controlled by Russia]. The day we left many people were walking that way.

Our convoy was made up of the residents of two nine-story buildings. No one else joined us. More private cars followed from the city center. It was easier to leave the center than the Left Bank district.

How did you pass the checkpoints?

The first was near Melekine. We passed it in a haze because as we approached the checkpoint, the front wheels of our car stopped moving. They started smoking and we poured water on them. There was something wrong with the car and we feared bad things would surely happen. At the least, we hoped to get clear of the city. There were two cats, a dog, two moms, a dad, a child and me in the car, with some of our belongings. As soon as we passed the checkpoint, we abandoned the car on the roadside.

Thank God there were people in the convoy who had an empty back seat in their vehicle. They did not pick up anyone else, they said, because they knew someone in our convoy might need the space. They sat us in their car and our bags were spread between the entire convoy. I wouldn’t see them again, I thought, and mentally said goodbye. Until we reached Manhush I was in a trance and had trouble remembering where my mom or my dog were.

The first Russian checkpoint I saw and recognized was in Manhush. Now I realized they were really here, standing in front of us. Sitting in the basement, I had not wanted to accept the fact. Now here they were, with white armbands carrying the letter Z. There were “DPR” police vehicles with chevrons and inscriptions – some commissariat or other, Soviet titles. They hung Russian flags at the checkpoints. We also saw DPR flags and red rags that may have been the old flag of the USSR.

We passed the Manhush checkpoint without a problem. They checked us over since we were driving through in another car. I travelled with a family, which included a young lad. He was not their relative and of an age the Russians were checking thoroughly. “Did he have any tattoos?” they wanted to know, and they looked through his bag, checking his gadgets and searching through the messages on his phone.

The driver was a pensioner. They did not bother him, they just checked his ID document. At each checkpoint – and there was one almost every 100 meters–they checked the lad for the same things. We passed some easily: a light check and on you go. At some they asked if we were carrying weapons or drugs and warned us to leave them behind. There was a scary checkpoint ahead, they said, where everything was checked very thoroughly: It would be best to leave it all with them. On some checkpoints the men who peered into the car with their red wind-tanned faces were drunk. They tried to ask something and to give us advice. Then there were young men, 18 or 20 years old, who spoke with an unmistakable Russian accent. They looked a bit more educated.

The DPR fighters came from nearby villages and were drunkards to a man. They were dirty and reeked of cigarette smoke and booze. They squeezed up against the car like pigs when they carried out their inspection. We decided not to provoke them: our task was to reach free territory. I wanted to ask, “Why are you standing there, what are you doing?” But I did not even look at them. I was a woman with a child, and they mostly checked the men. Some seized small things like cigarettes, candy or cookies. One group of fighters saw we had a video recorder in the car. It was turned off and not recording anything, we explained. We asked them to leave it but – no! –they grabbed it.

We reached Tokmak in a hurry, to get there before the curfew began at 6 pm. The “Olympic” kindergarten gave us shelter and it felt like Heaven although Tokmak was already occupied. It was quiet and calm there. The occupiers probably knew that Tokmak was receiving convoys of displaced people all the time. Each night a new group of people slept there. We could wash! My head was so dirty that I covered my long hair witha kerchief – I was afraid of lice. Everyone else went to eat but I ran to wash. After three weeks in a dusty basement we were very grubby. Then they gave us food: hot soup, pies, pickles, bread, pancakes, and tea. It was a warm welcome for which I am very thankful. It’s surprising that people under occupation could give us such a pleasant reception.

We left in the morning, warned that there was a scary checkpoint ahead in Vasylivka village. The convoy ahead of us came under fire. I don’t know if there were casualties. We passed them and I saw Grad shells stuck in the road. (My husband didn’t bother telling me to be brave.)

The bridges had been blown up and we had to follow a route through villages far from the main road. Somewhere beyond Vasylivka there was a gray zone not under the control of “ours” or “theirs”. The next checkpoint was one of ours. A soldier approached, and there were tears of joy on our faces when we heard him speak Ukrainian. They wore blue armbands and flew Ukrainian flags. We received a warm reception and gave them candies. Then we waited three hours, like all the other convoys, until a large number of people had gathered. The cars stretched back for many kilometers. The police arrived and they went with us to the city of Zaporizhzhia. It was our first stop in Ukrainian-held territory. There our names, car license plates and phone numbers were recorded in the lists of evacuated people.

I entered a store and burst into tears. It was like normal everyday life. That’s what we were used to: I had only spent eleven nights in the basement. How did people who spent two months in such conditions survive? My son had suffered greatly and even now he sometimes has panic attacks. He behaves as usual and then, suddenly, he becomes hysterical. It happens before going to sleep, the time you lie down and start thinking. He cries and misses his home, his friends, and his school. We must find links, I’ve read, to anchor us in our previous life. It’s very hard to find them now.

Were there people who evacuated to Russia?

There were many, and it came as a surprise, because I never considered such an option under any circumstances. It was out of the question! If that was my attitude, I believed, others would not want to go there either. But people had suffered a great deal, and everyone found their own way out, especially those without cars. You only had a one-in-ten chance of survival if you tried to walk from the Left Bank district to the Melekine road.

Did anyone from your courtyard or building stay behind?

Yes, some stayed. Especially older people.Those who lived with us in the basement. Ours was a big building of nine floors and six entrances.

What are your immediate plans? To go abroad?

No, I’m not planning to go abroad. It was hard enough without my husband. Maybe I was thoughtless and hoped it would all end soon – I did not expect such a nightmare. There were even trains for evacuees in the first days, and some took them.

It’s difficult to make plans. I have to live. I need to work and support the family. But it’s hard because my thoughts are still back in Mariupol. I’m positive that I won’t go anywhere outside Ukraine. I cannot imagine myself in another country. There wasn’t a day when I did not break down and cry. Visit my Facebook page and you’ll see the news section is full of missing people.

What else did you see that might be considered a war crime?

- A young family lived on the ground floor of our building. Their father visited them and talked about Vinogradne where he lived. Russian soldiers came and said: “We are going to live in this house. Leave.” They did not even let him pack his things.

- We have a good friend whose parents also live in Vinogradne. On 4 March he visited them. When he left their courtyard, DPR fighters were driving along the street. They captured five people walking there and he was number six. “Either we shoot you here and now,” the fighters said, “or you get into this car.” He had told his wife he would visit his parents and return at once. Then he went missing. Later we were told he was taken east to Bezimenne village [on the Azov Sea coast].

- The invaders broke into apartments and pillaged them: for instance, our neighboring building, No 60.

- A woman on the eighth floor looked out the window. A sniper shot her in the eye and killed her.

- Our friends heard Kadyrov’s fighters under their windows. When we were leaving, our friends’ dad called us. He went to check on their apartment, he said, and found the door open and Chechens living inside. They were lying on the sofa and using his apartment. They didn’t do anything to him, thank God: they just checked his documents and told him to get out. That was at 54 Morsky Boulevard.

- A neighbor called us. The enemy had set up a gun post on the ninth floor, she said, and wrecked her apartment. “There’s nothing left,” she said. “I don’t know what’s still there.”

- On 2 March, the balcony windows in my apartment were smashed. Pieces of shrapnel hit every apartment looking out at the sea: the size varied from day to day. People showed us the fragments, some were quite large. Thick torn chunks of metal. A piece of shrapnel might be small but heavy. They came from cluster bombs.

- A friend of ours died on 18 March. He lived in a private house in the Left Bank district. A shell fell in his yard or nearby. A fragment hit him in the temple, and he died instantly. That was at 45 Chkalov Street.

Translation, Vitaly Konkin and John Crowfoot