Russia’s use of totally anonymous ‘witnesses’ in the trials of political prisoners has already been condemned by, among others, the UN Secretary General in his 2021 report on occupied Crimea. It now transpires that Russian courts are not only willing to ignore the lack of any grounds for witnesses testifying in secret but will also ‘adjust’ such ‘testimony’ should it not suit the prosecution’s case.

The ‘secret witness’ used by the FSB for its latest prosecution of four Crimean Tatar civic activists on profoundly flawed charges failed to recognize one of the defendants – Rustem Taiirov. Since these anonymous individuals provide virtually the only sources of ‘evidence’ used to justify sentences from 12 to 20 years, the fact that the witness did not point to Taiirov in an identification parade was clearly of critical importance and highly inconvenient for the prosecution. Both the Russian prosecutor Igor Nadolinsky and a panel of judges at the notorious Southern District Military Court in Rostov, however, decided to treat the witness’ identification of Person No. 2, when Taiirov was No. 3, as a “typo”.

According to lawyer Emil Kurbedinov, the situation came to light during the questioning of a formal witness used during the identification procedure. The FSB protocol stated that the anonymous witness had chosen Person No. 2, and had therefore, from a legal point of view, identified the wrong person. Kurbedinov notes that the defence watched as both the prosecutor and the court tried to present the matter as being a mere typo. This, however, was refuted by the formal witness present during the identification parade and afterwards, when the anonymous witness was given the protocol to read and sign. There had been nothing, the formal witness said, to indicate that No. 2 had been written by mistake, and not because this was the individual that the ‘witness’ had wrongly identified as Taiirov.

Although especially shocking, this was not, by any means, the only occasion where judges at the Southern District Military Court have turned a blind eye to obvious problems with anonymous witness ‘testimony’. Such witnesses are usually able to repeat the key points of the prosecution’s indictment, while proving quite unable to describe the home or mosque at which they claim to have met the defendant on many occasions. In at least one case, the anonymous witness changed his ‘testimony’ to fit the altered indictment against civic activist Rayim Aivazov after the latter refused to be silent about the torture he had faced. At the same time, they not only dismiss the defence’s demand that the witnesses’ identity be revealed, but actively block questions by the defence aimed at demonstrating that the witnesses are lying (and may not even know the defendant).

Russia has, since 2015, been illegally imprisoning Crimean Tatar and other Ukrainian Muslims on profoundly flawed ‘terrorism’ charges, although the men are accused solely, and without any real evidence, of involvement in the peaceful transnational Muslim Hizb ut-Tahrir party which is legal in Ukraine. Russia uses a secretive ruling by the Russian Supreme Court in 2003 that declared Hizb ut-Tahrir ‘terrorist’ to sentence men for such unproven ‘involvement’ to 20 years’ imprisonment or longer. In occupied Crimea, it increasingly targets civic journalists and activists, particularly those from the Crimean Solidarity human rights movement.

The FSB often claim to have found ‘prohibited religious literature’ during the armed ‘searches’ of the men’s homes, but increasingly bring the books with them. Aside from such questionable ‘evidence’, the prosecutions are based on the testimony of anonymous witnesses and, usually, illicitly taped conversations, sent for ‘assessment’ to FSB-loyal ‘experts’.

In this case, three of the defendants – Rustem Taiirov, Rustem Murasov and Dzhebbar Bekirov were illicitly taped having a conversation about making a call to Islam and citing parts of the Quran. The men also discussed tactics for speaking, arguing or debating with Muslims and other believers, such as Christians. The participants in the discussion agreed that one should speak politely, accurately and with restraint, and without angry interrogation. Murasov, for example, spoke of his meeting and dialogue with Jehovah’s Witnesses.

None of this proves involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir, and the participants show tolerance for others’ views. Yet this dialogue as well as the testimony of at least one ‘secret witness’ who wrongly identified one of the defendants, will likely be used to sentence the men to 12 – 14 years in the worst of Russian penal institutions.

The Russian Supreme Court made no attempt back in 2003 to explain why an organization which was not known to have committed any acts of terrorism anywhere in the world should be labelled ‘terrorist’. Emil Kurbedinov told Crimean Solidarity that the defence has provided the court with courts of formal requests to Russia’s department on fighting terrorism, asking for information about the activities of Hizb ut-Tahrir. They specifically asked whether the organization had organized or planned any acts of terrorism in the Russian Federation or occupied Crimea. They received three ‘answers’: the first said that they had no information about any acts of terrorism; the second claimed that the information was secret; while the third simply referred them to the Crimean FSB who essentially gave no response.

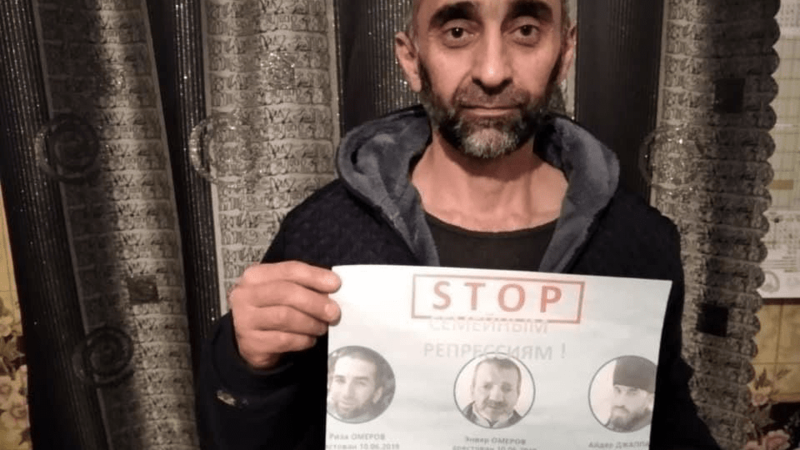

Five Crimean Tatars were arrested on 17 August 2021, all of them men who had previously taken part in acts of solidarity with political prisoners, had attended political trials, etc.

Raif Fevziev, a local imam and civic activist, was put on trial separately, accused of ‘organizing’ a Hizb ut-Tahrir group on the basis of a discussion about Islam in his own home seven years earlier.

See: The Face of Russian terror against Crimean Tatars

Zavur Abdullayev; Dzhebbar Bekirov; Rustem Murasov and Rustem Tayirov are now on ‘trial’ at the same Southern District Military Court. Bekirov is charged, like Fevziev, with the more serious ‘organizer’ role (under Article 205.5 § 1 of Russia’s criminal code) and faces a sentence of 17 years or more. Abdullayev, Murasov and Taiirov are charged with ‘involvement’ (under Article 205.5 § 2), with the sentences around five years lower, but still horrifically high. It is likely that all have also been changed with Article 278 ‘planning a violent seizure of power and change in Russia’s constitutional order”. The Memorial Human Rights Centre earlier spoke of this extra charge of being used in Russia as a punishment for refusing to cooperate with the prosecution (by admitting the charges, or at least agreeing to state-appointed lawyers). In occupied Crimea, the charge has become a standard addition, although no proof at all is ever provided.