We thought that help would soon come to Mariupol

In February, we still didn’t understand what was happening. We hoped that this would end soon, like in 2014. We thought that help would soon come to Mariupol, so we just waited. My family at that time consisted of me, my wife, a 92-year-old mother-in-law, and a disabled son. Artem is 21 years old and non-verbal autistic. In April, my mother-in-law could not stand it all and died, and I buried her on the lawn near the house.

Subsequently, another problem arose: a shortage of food and water. I had to spend a lot of time searching. We were lucky because there was a large store nearby where we found a lot of wooden pallets. We took them apart and burned them. The food was prepared near the entrance together with the neighbors. We learned to exchange products with each other. Some had potatoes, some had carrots, and so we made dinner for everyone.

We didn’t go to the bomb shelter because we live on the ninth floor. The elevator didn’t work, and our basement was too deep. There’s a staircase about five meters down there, and you had to jump. My mother-in-law and my son would not have been able to climb there. Therefore, my wife and I said, “Whatever will be — will be.”

I saw a tricolored [Russian flag’s colors] tank shooting at houses

In mid-March, the occupiers entered. Several tanks stopped near the house’s parking lot to create a deployment site. Our fire was 20-30 meters away. The tankers approached us several times, asked for tea, and offered us cigarettes. One constantly emphasized: “I am, by the way, from Moscow.” And then he got pretty drunk on vodka and said: “They didn’t take me into the army because at the trial, the prosecutor said that I was a maniac!” We understood that he was serving a sentence for sexual assault. It was apparent just looking at him. Then, another looked around: “Why is all this?” I answered: “Listen, they said that you have had the same in Donetsk for eight years...” — “What are you saying? We have elevators and trolleybuses running, but here... Ashes!” At least one person was horrified by what they did. They were not dressed so well and complained that they were thrown here like cannon fodder.

I saw with my own eyes how a tricolored Russian tank was spinning through our streets. One day, it was warm. We were sitting at home and suddenly heard a shot nearby. It flew into the elevator shaft on the roof above us. Then, this tank shot at all the elevator shafts in the building opposite. After that, he took on the five-story building. It was shot methodically, from top to bottom, until the house caught fire.

I ran down and saw several men standing at the intersection and shouting: “What are you doing?!” And he got out of the tank: “There might be a gunner or a sniper there!” And he continued to shoot at the houses. By then, no fighting had happened in our area; there could be no spotters.

On 20 May, I was arrested

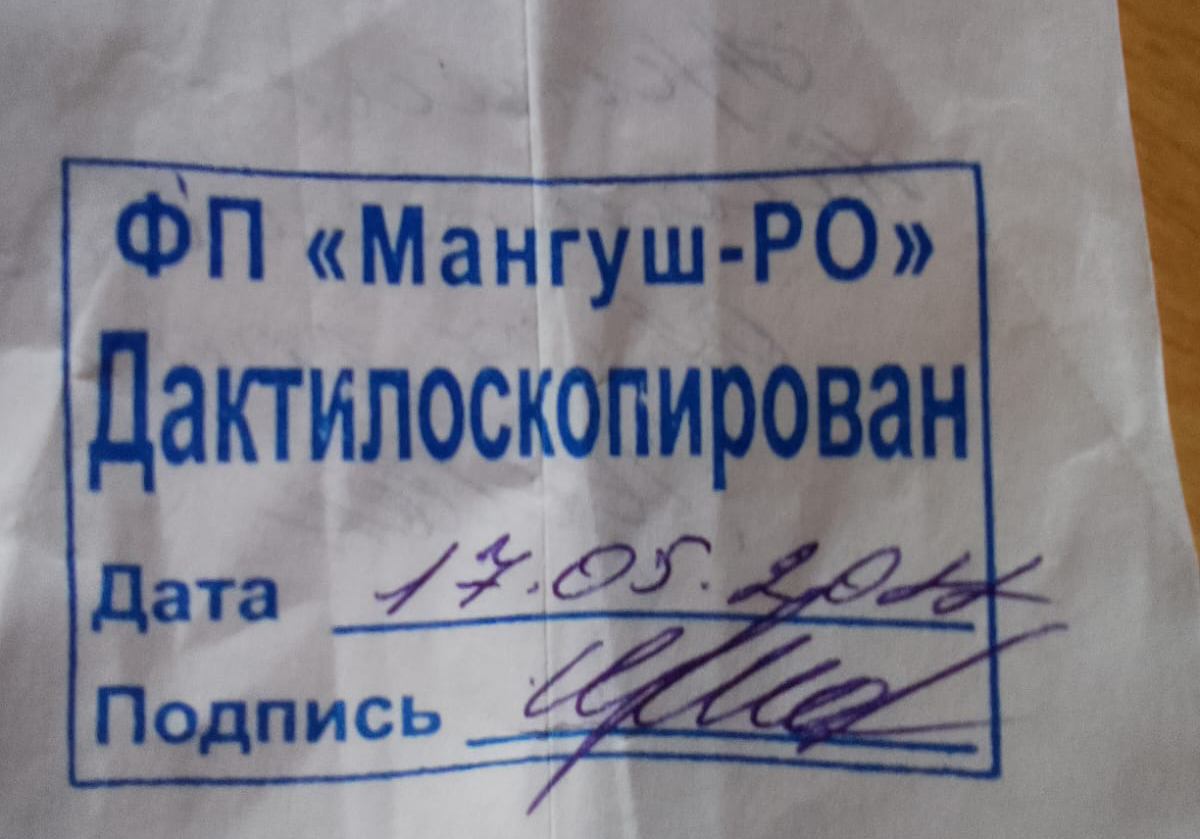

When the fighting moved closer to Azovstal, I began to look for a way to leave. Then, it was still possible to go to Zaporizhzhia. But the entire city was occupied, and the occupiers had already begun to establish their own rules. To get through the checkpoints, you had to go through a filtration procedure. It was in Mangush, and we went there.

Later, during interrogations, I realized that a denunciation had been written against me, perhaps more than one. But the person who wrote the accusations did not know where I lived. Unfortunately, during filtering, I had to show documents and registration. On 17 May, my family and I went through filtration, and on 21 May, we were going to go to Zaporizhzhia. But on 20 May, I was arrested, and a criminal case was opened against me. Charges were brought against me for several posts on Facebook, which they interpreted as extremism, incitement to terrorism, inflaming national and other hatred.

My wife went grocery shopping that morning, and I was at home. Someone knocked. Two guys, 20-25 years old, stood behind the door. One of them put a gun to my stomach and started shouting something. They immediately began a search, unpacking everything in the apartment and taking away the phone and tablet. I was told to get ready. At this time, my son was in another room. I asked them to wait until my wife came not to leave Artem alone. But they didn’t allow it. I had to ask my neighbor to sit with him.

They put me in the car, stopped in the middle of the street, and asked what I wrote on FB. The impromptu interrogation lasted about 40 minutes. Then they said: “Okay, they’ll deal with you there!” I asked: “Where are we going now?” — “And now to Donetsk.”

They pulled an ordinary plastic bag over my head. Then, there was another interrogation. They talked to me as if I were an officer of the Third Reich. “Your nationalist beliefs? We will show you a statement of cooperation with the SBU.” We arrived in Donetsk in the evening. In Donetsk, other people took fingerprints and interrogated me again. They asked about my performances, creative activities, and posts on Facebook.

In “Isolde”

Around 1 a.m., I found myself in the infamous “Isolation”. People call it “Isolde”. In 2014-2015, it was a terrible torture facility; many were simply killed there. The conditions there are harsh. The walk is only in name, maximum — three minutes. Wash — three minutes. During the day, you cannot sit or lie down on the bunk. There is a small, uncomfortable bench; you can take turns sitting on it or walk all day long. After 16 hours on your feet, you get terribly tired.

The guards beat people. However, I was lucky: a kick in the back a couple of times doesn’t count. There was one guy (18 years old) who was imprisoned for cooperation with the Armed Forces of Ukraine. He was forbidden to sit during the day at all. By the time I arrived, he had been standing for 16 hours a day for two months. Once he put one foot on the bunk, the guards immediately ran in and beat him.

We could be punished for any offense. When the door to the cell opens, everyone must turn their backs and put bags over their heads. The guards were afraid that you would see them and remember them. Each of the prisoners dreams of taking revenge on them if he survives. There were no transfers from outside. All the time, in isolation, I didn’t even know if my family knew where I was or what was wrong with me.

The examination found that I called for the Kremlin arson

On 16 June 2022, I was introduced to the investigator. It was a woman. Charges were brought, and an investigation began. From ”Isolda”, I was transferred to a pre-trial detention center on Kobozeva Street. This vast prison, built in the 50s of the last century, looked like a prison from Stalin’s times.

In the pre-trial detention center, I was in three cells. Until October, I was in a cell for four. It’s the size of a train compartment. Inside is a bucket, wash basin, and a small table for eating. If two people stand up, the other two must lie down because there is no more room. Of my three neighbors, two were murderers. There were terrible unsanitary conditions and bedbugs.

In October, I was transferred to political criminals. There were cockroaches and rats there. There was a shower once a week with ice-cold water. In the first cell, with 25 places, 29 people had to take turns sleeping. Subsequently, I was transferred to the next cell, where there were 18 places for 21 people. I slept again every other night for a few days until someone came out and a place became available.

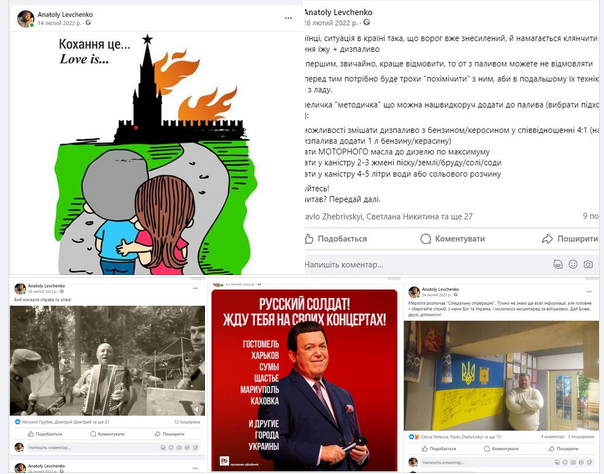

On June 16, I was charged under Article 328 of their code for inciting hatred. All accusations were based on denunciations and posts from my social networks. In October, they opened cases under two more articles — incitement to extremism and terrorism. They found a post on Facebook with a picture of a “Love is...” chewing gum wrapper. A boy and a girl sit there, holding hands and looking at the burning Kremlin. Below is the caption: “Love is when you look in the same direction.” The examination established that, in this way, I called for the Kremlin arson. The three cases together could result in a seven to nine-year sentence.

Write that it was a joke

After a pseudo-referendum was held on 4 October, the territory of the occupied Donetsk region allegedly “became the Russian Federation.” It meant that all resulting proceedings must be reviewed under Russian law. Article 328 in the code of the Russian Federation (inciting national hatred), unlike the code of a pseudo-republic [“DPR” — Donetsk People’s Republic], is not criminal when such a crime is committed for the first time and is punishable by administrative liability. It became clear in October, but they released me only in March.

I still don’t know the fate of the other two cases. They initiated them on 14 October according to the laws of the “DPR”, but from 4 October, the legislation of the Russian Federation was already in force. That is, they got themselves confused. On 9 March, I was released on my own recognizance, and the case was closed under Article 328. I went to Donetsk to see the investigator to rewrite papers in April and May. A new protocol was drawn up in retrospect: “Write that you were joking,” the investigator said. I have no documents that these cases have been suspended.

In Mariupol, I began to ask for help to leave for Ukraine. Having a son with a disability, we could not get on the bus. We needed separate transport. Four months later, we collected the necessary amount and found a driver. I had to get Russian passports. It’s shameful, but there was no way around it.

There is your Ukraine

On 20 July, we left Mariupol, and at nine in the morning the next day we arrived at the Kolotilovka-Pokrovskoye border crossing point. Of course, we were prepared because we knew that at the checkpoint, they could check our phones and put us behind bars for any trifle. No photos, no Ukrainian symbols, Ukrainian telegram channels, contacts — all this had to be cleaned out. We were lucky that the FSB guys didn’t harass us too much, because Artem threw a tantrum.

They tell you if you pass the test: “Well, go, there is your Ukraine.” You can only cross the checkpoint on foot. You need to walk two kilometers between the Russian and Ukrainian checkpoints. This was once an asphalt road, but now it is covered with gravel and plowed, with mines lying on the side of the road. It’s a gray no man’s land.

We saw a tower with a Ukrainian flag in the middle of this gray zone. It was shabby, but Ukrainian. And then I told my wife: “Stop, I have to say a few words in Ukrainian on the video.” We stopped. In Mariupol, it was impossible to speak Ukrainian. It immediately aroused suspicion. Despite the heat and everything, I was happy I could use my language again.

Now Anatolii Levchenko lives in Kropyvnytskyi, where he dreams of reviving the First Non-State Theater of Donbas (Mariupol): “Terra Incognita, your theater for your people.”