On 24 February 2022, I was in the city of Irpen, where I lived. The war found me, like the vast majority of Ukrainians, in bed. That day, I was getting ready for work. It was my filming shift — I worked as a second director on a feature film. I spent the first ten days of the invasion in Irpin: I heard explosions and shelling.

We spent these first ten days with my parents in a house that I rented. I heard a fighter plane carry out an airstrike on the Novoirpinski Lypky residential complex. A shell hit one of the houses where my friend bought her mother an apartment. It was scary when I heard the sound of a tank driving along the neighboring street. Even if you have never heard what a tank sounds like, you will not confuse this sound with anything else.

The worst thing is not the sound of the tank itself, but the moment when the sound stops. You understand that the tank has arrived at the position, and the turret will now turn around, and a shot will follow.

That is, you need to hide quickly because the shot may be in your direction. It is also difficult to confuse the sound of a fighter jet with anything because, at such a moment, your body reacts separately from your consciousness. Namely, you are already hiding before you have time to think that you need to hide.

We spent the last three days before the evacuation down on the floor. Even then, I joked that we were getting down and dirty. We ate on the floor, slept on the floor, and read the news on the floor. The shelling was so intense that it was dangerous to stand upright.

On 4 March, I decided to evacuate. On the morning of 5 March, I collected a few things: hard drives with work materials, a laptop, my kittens in a carrier, and a few essentials. And with all this, I went to the station in Irpin. There, we waited for the evacuation train. One of the carriages is now on Mykhailivska Square in Kyiv as an exhibit.

It was in that carriage that I was supposed to travel from Irpin to Kyiv. But we were informed about an attack on the train; it went off the rails, so we could not evacuate, and we all needed to get to the destroyed bridge near Romanivka. This bridge was later called the “bridge of life.”

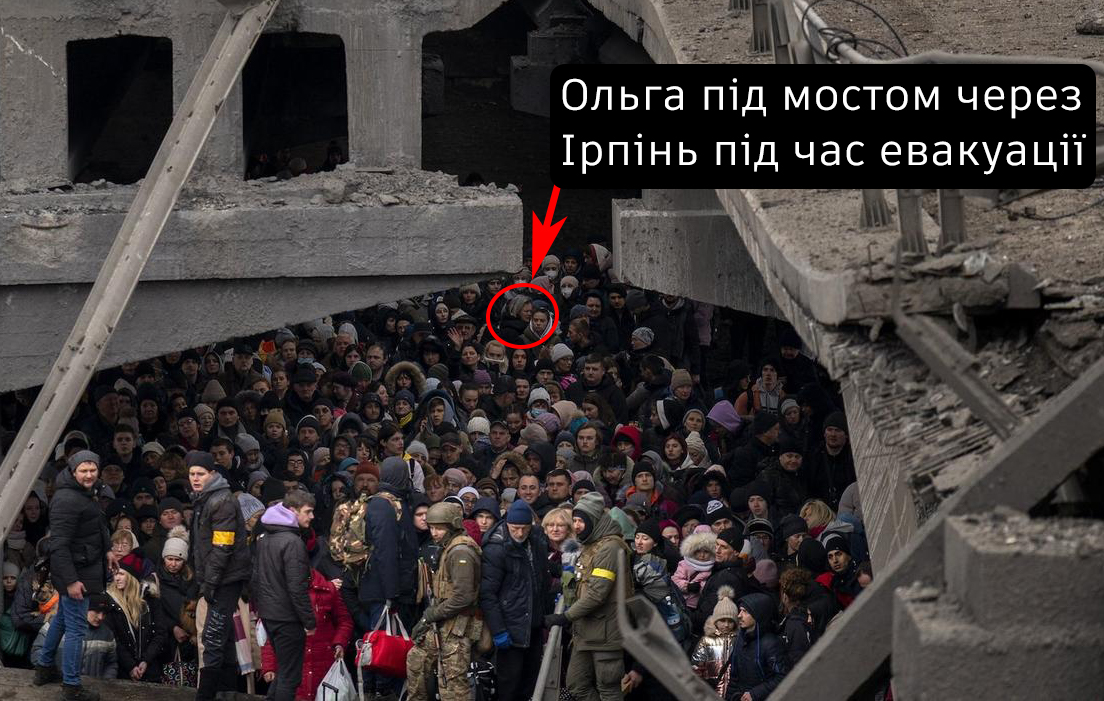

I was lucky once again — I found the phone number of a local volunteer who picked me up, my backpack, and my cats and drove me to the bridge. Then I spent some time under the bridge because we were waiting in line to cross: they let us through in groups.

After crossing the bridge, I got to the buses. I even made the news because Maryna Poroshenko[1] helped me get on the bus. Then, all my friends sent me screenshots from the news, where I had an incomprehensible and distorted face on my head (smiles). I joked that the moment had come when the country saw me, but I looked like this.

Do you know about cases of war crimes by Russians in Irpin?

I heard the story of a manicurist who served my mother. During the shelling, she was in the courtyard of her own house with her husband.

Before her eyes, her husband died from shrapnel; she had to bury him in the yard with her own hands. After this, she realized that if she also died, there would be no one to bury her.

She walked at her own risk along the street under fire. She simply no longer understood what she was doing, being in shock. Fortunately, she was able to evacuate.

Some other friends of mine remained under occupation. They had to stay at home because they were afraid to go out. After all, there were Russians there.

Was your property damaged?

I lived in rented housing. Fortunately, neither my apartment nor my parents’ apartment was damaged. All that was damaged was our car. We parked it in the backyard, and a mine flew there. The car had to be sold for scrap.

On 6 March 2022, I left Kyiv for Lviv, where my friends awaited me. I spent two days there. In April and May 2022, I was in Berlin. I tried to integrate there, but, as it turned out, the life of a migrant was not very suitable for me. Therefore, I decided to return to Ukraine.

Will I return to Irpin? Maybe. But now I live in the city of Turka, in the Lviv Region. I have a job here. I’m working, and I’m needed.

[1] Petro Poroshenko’s wife. He served as the fifth president of Ukraine from 2014 to 2019.