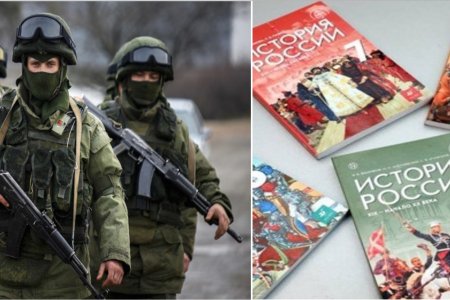

Russia’s education ministry is planning to exclude the Ukrainian language from the curriculum imposed on occupied parts of Ukraine, with this likely to take effect from September 2025. The ministry claims that the exclusion is “in connection with the changed geopolitical situation in the world”. In other words, in connection with Russia’s invasion and illegal occupation of Ukrainian territory.

While undoubtedly outrageous and illegal, it would be hard to call the move unexpected. Russia began systematically eliminating the Ukrainian language from schools immediately after its invasion and annexation of Crimea. The same processes were seen in the Russian proxy ‘Donetsk and Luhansk people’s republics’ [occupied Donetsk].

The change proposed by the Russian ministry will mainly affect occupied parts of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts where, according to the ministry, Ukrainian as native language has, up till now, been taught in all schools as a mandatory subject. Ukrainian as native language was also taught, where parents specifically asked for it, in occupied Crimea and Donbas, Statistics are not available, and Russia has, at least in occupied Crimea, consistently tried to conceal the real situation. From 2014, pressure on parents to reject Ukrainian education for their children, even where in theory possible, was intense and systematic, with it then falsely claimed that Ukrainian was not taught because “there was no demand for it”. Since 2022, the risks to parents and children of any such clear affirmation of Ukrainian identity would also be significant.

Russia met with huge resistance in occupied parts of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts from teachers who refused to collaborate with the invaders and to encourage parents to do so. After several teachers and school heads were abducted, many others would have left occupied territory. There have also been reports from occupied territory of Ukrainian teachers being forced to retrain to teach Russian.

At the end of March 2023, RIA Melitopol reported that the occupation regime in Melitopol (Zaporizhzhia oblast) had held a meeting at which they informed teachers of Ukrainian language and literature that they were “no longer needed”. The teachers would be allowed to work till the end of the school year and then made redundant. RIA Melitopol cites a Melitopol resident who said that when the kids said that they wished to study Ukrainian, they were told that their native language is Russian, and asked if they’re not “waiters” – a word the invaders use for those on occupied territory who are longing for liberation by the Ukrainian Armed Forces. The threat would be clear – if not to the children, then to their parents. On any territory that falls under Russian occupation, it is dangerous to demonstrate commitment to Ukrainian identity, including the Ukrainian language

Despite the abductions, harassment and threats, resistance, at least in occupied Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts, does not appear to have been crushed. Almost exactly a year ago, Viktor Kovalenko, Chief Editor of Berdiansk 24, told Radio Svoboda that “for the occupiers, there is no crime more terrible on occupied territory than somebody or something’s identification as being Ukrainian. They’re not particularly bothered by murders, rape, the abduction of people, just what bears some hallmarks of Ukrainian identity – language, shop signs. They get very wound up about Ukrainian number plates on cars. That is for them the most terrible crime…”. They react, he says, by imposing fines, or by taking people away and imprisoning them in basements where they are invariably subjected to torture.

Kovalenko recalled a ‘questionnaire’ issued in occupied Berdiansk, on whether subjects should continue to be taught in Ukrainian in schools. A majority wanted it to continue, with this the last that was heard of the said questionnaire, with no further measures taken.

In fact, the measures are now being taken, with the aggressor state now dropping any pretence by proposing to remove the subject of Ukrainian as native language from the curriculum altogether. This is claimed by the Russian ministry’s draft order to be because of the so-called “changed geopolitical situation”.

Russia was more concerned about optics before 2022 and even claimed there to be three ‘official languages’ in occupied Crimea: Ukrainian, Crimean Tatar and Russian. This is on paper alone, as children and their parents have long known, and as Crimean Tatar political prisoners have learned when they tried to address ‘the court’ in their native language.

The proxy ‘Donetsk and Luhansk people’s republics’ were much more open, with ‘DPR’ dropping Ukrainian as ‘state language’ back in March 2019 and ‘LPR’ removing Ukrainian from schools a month later.

Nor is it only Ukrainian language in schools that the aggressor state immediately tries to eradicate. It was clear from documents uncovered after Balakliia in Kharkiv oblast was liberated in 2022 after several months under occupation that the invaders had immediately set about removing Ukrainian books – literature, history, etc. from schools. The same has been reported from other places under Russian occupation.