A month has passed since Tofik Abdulgaziev was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumour, yet no action has been taken on the operation urgently needed and the Crimean Tatar political prisoner remains imprisoned in Russia, thousands of kilometres from his wife and children.

Aliye Kurtametova reported on 20 January that her husband’s condition has worsened. She had been extremely worried, she explained, when her husband did not ring at the time agreed. He had already begun having spells where he loses consciousness, and it was his dramatic loss of vision that probably prompted the prison hospital doctors to send him for the scan which, at the beginning of December, first found that he has a brain tumour. He had also told her, two days earlier, that he has serious problems with coordination and finds it difficult to walk.

Tofik was finally able to phone on 20 January and spoke (when pressed) of serious dizziness and nosebleeds, and of a dangerously high blood sugar count (11 mmol/L, which is indicative of hyperglycaemia). Asked what the doctors had said, he replied that he had not yet seen them. It is not clear whether he meant that day, or over a longer period, however Aliye earlier wrote that she had been unable to track any personnel down throughout the prolonged New Year and Christmas holidays (around 11 days).

“There are no words to express the feelings when you’re forced to speak with a person dear to you while clearly understanding that it could be the last time. When your husband could get worse at any moment, with nobody there with him.”, she writes, asking how it is possible to endure such thoughts.

“Together with lawyers I have been knocking on all doors for years, appealing to the letter of the law and to humanity. After all, Article 81 of Russia’s criminal code stipulates that Tofik’s diagnoses are on the list of illnesses precluding his imprisonment. Yet the only response is silence.

Where else can we turn so that we’re heard? I beg to be heard. His condition is extremely critical. We have already lost our brother Dzhemil Gafarov. At that time, his family also asked for help, yet the silence then was deafening.”

It is indeed true that Russia has legal regulations regarding who should not be in detention. There have even been isolated cases where political prisoners have been released because of grave illnesses.

Russia is, however, demonstrating particular brutality in its treatment of Crimean Tatar and other Ukrainian political prisoners, very many of whom, like Tofik Abdulgaziev and Dzemil Gafarov, were targeted for their human rights activism. In the two cases where courts in the Russian Federation complied with Russia’s own law and ordered the release of Crimean political prisoners, the rulings were challenged by the Russian prosecutor and overturned. 58-year-old Lenur Khalilov, who is suffering from cancer, and Oleksandr Sizikov (41), who is blind and disabled, have already been forcibly returned to the horrific conditions of Russian penal institutions.

Both Dzhemil Gafarov and Tofik Abdulgaziev were arrested on 27 March 2019 in Russia’s worst offensive to date against Crimean Tatar civic journalists and activists of the Crimean Solidarity human rights movement. Dzhemil Gafarov (born 31.05.1962) had fourth stage chronic kidney disease (one level before kidney failure) and had, as a result, suffered a serious heart attack in 2017. He should never have been taken into custody at all, yet this, and his increasingly critical condition, were ignored by ‘judges’, prosecutors and prison staff. He died, after almost four years of torment, in a Russian SIZO [remand prison] on 10 February 2023.

In a very few cases, the Russian FSB have clearly understood that their victims will not survive until the predetermined sentence and have had a person placed under house arrest until the sentence comes into force. This was true of Oleksandr Sizikov, and of Amet Suleimanov, a Crimean Solidarity civic journalist who had been forced to give up his activism due to grave and life-threatening conditions. He urgently needs a heart valve transplant and is in a dangerously weak condition in Russian captivity with essentially no likelihood that he can survive the horrific 12-year sentence in reprisal for his civic position and refusal to stay silent about Russian repression.

The same is true of Tofik Abdulgaziev, with the main difference being that the civic activist was in perfectly good health when seized on 27 March 2019. While the brain tumour may not be directly attributable to the conditions in Russian captivity, Abdulgaziev contracted tuberculosis and some other conditions because of his imprisonment, with these doubtless leaving him gravely weakened and his organism considerably less able to fight the cancer.

As reported, Abdulgaziev has been in prison tuberculosis hospital No, 3 in Chelyabinsk since March 2024, and was, on 22 March 2024, placed in a critical care ward in a grave state. By the time his family were allowed to see him, he had lost around 40 kilograms and was gaunt and frail. In late April 2024, he was diagnosed with disseminated tuberculosis of the lungs, with this having spread to the chest lymph nodes. The doctors also found a number of other serious, some life-threatening conditions - double pneumonia; fluid in the lungs; medium severity anaemia; connective tissue dysplasia with damage to the mitral valve (valvular heart disease); chronic heart failure; chronic gastritis and kidney stones. He should then have been released on health grounds, but remained, getting weaker and weaker. On at least one occasion, the prosecution organized its own supposed expert assessment which claimed that Abdulgaziev did not have illnesses that could prevent him from remaining in prison, with this used to justify a formal refusal to comply with Russia’s own legislation and free him.

Tofik Abdulgaziev (b. 19 July 1982) and Aliye have three children – Amar (b. 2005); Medina (b. 2010) and Yarmina (2015) and were also bringing up Aliye’s daughter, Sayire from her first marriage. Abdulgaziev had ignored earlier warnings and clear signs of the danger of civic activism, and played an active role both in Crimean Solidarity, and in the linked Crimean Childhood organization, which particularly provides support to the children of political prisoners. Abdulgaziev actively visited political trials, organized parcels for political prisoners, was sound operator for recordings, and organized activities for children traumatized by the armed raids and arrests of their fathers.

He and his family were subjected to a first armed search on 4 May 2017, with such methods used by the FSB as a ‘first warning’. It was one that Abdulgaziev could not heed, and the FSB came back for him on 27 March 2019.

The arrests that day so blatantly targeted men involved in highlighting repression and helping the victims of persecution that international condemnation was finally vocal. Human Rights Watch called the arrests “an unprecedented move to intensify pressure on a group largely critical of Russia’s occupation of the Crimean Peninsula” and stated unequivocally that attempts “to portray politically active Crimean Tatars as terrorists” is aimed at silencing them. There was similar criticism from the US State Department ; the EU ; Freedom House and Civil Rights Defenders, and the Memorial Human Rights Centre was swift to declare all the men political prisoners and denounce the attempt “to crush the Crimean Tatar human rights movement”.

All of the men were charged only with ‘involvement’ in the Hizb ut-Tahrir movement, a peaceful transnational Muslim organization which is legal in Ukraine and not known to have carried out acts of terrorism anywhere in the world. Russia has never provided any grounds for its highly secretive 2003 Supreme Court ruling that declared Hizb ut-Tahrir ‘terrorist’, yet this inexplicable ruling is now being used as justification for huge sentences on supposed ‘terrorism charges’. Five of the men faced the more serious charge of ‘organizing’ a Hizb ut-Tahrir group (Article 205.5 § 1 of Russia’s criminal code), while the others, including Abdulgaziev were accused of ‘taking part’ in such an unproven group. The aggressor state, which invaded and annexed Crimea also charged the 25 Ukrainian citizens with “planning a violent seizure of power and change in Russia’s constitutional order” (Article 278).

The prosecution claimed that the ‘proof’ to back these charges came from innocuous discussions about religion, politics, courage which were illicitly taped back in early 2016. Three years elapsed before the FSB carried out the arrests, making the ‘terrorism’ charges seem especially preposterous. Faulty transcripts of these conversations were sent to FSB-loyal ‘experts’ who are chosen for their willingness to ‘find’ whatever the FSB demands of them. The defence obtained independent expert assessments by people actually qualified in their field. Their analysis of the supposed expert assessments was damning, but ignored by the court.

As in all of these ‘trials’, the judges collaborated with prosecutor Yury Konstantinovich Nesterov in allowing anonymous or secret witnesses despite the lack of any evidence that these ‘witnesses’ would be in danger if they testified openly. There is considerable evidence that ‘anonymous witnesses’ are often people who have themselves been tortured and / or threatened with imprisonment if they do not collaborate with the FSB. It is invariably these alleged witnesses who claim to have heard the defendants admit to being members of Hizb ut-Tahrir , or similar. They almost always claim to remember particular ‘incriminating conversations’ while demonstrating total ‘amnesia’ about everything else. In the last report on occupied Crimea from UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres , there was particular criticism of Russian convictions based almost exclusively on anonymous testimony, and of the role played by Russian judges in upholding such practice and preventing the defence from exposing the flaws in this alleged ‘testimony’.

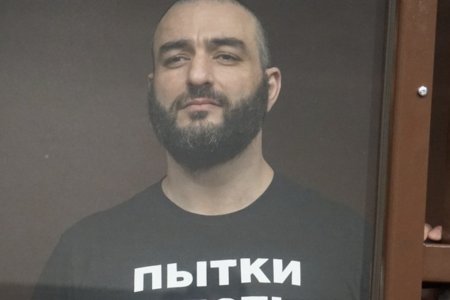

Russia split the 25 political prisoners into five groups, staging the same cloned ‘trial’ with each. Tofik Abdulgaziev was found ‘guilty’ on 12 May 2022, together with four other civic activists: Bilyal Adilov (b. 1970); Vladlen Abdulkadyrov (b. 1979): Izet Abdullayev (b. 1986),; and Medzhit Abdurakhmanov (b. 1975). Presiding judge Rizvan Zubairov, together with Maxim Nikitin and Roman Saprunov from the Southern District Military Court sentenced Adilov to 14 years; Abdulgaziev and the other men to 12 years. In all cases the first five years were to be in a prison, the worst of all Russia’s penal institutions. These shocking sentences against evidently innocent men were upheld on 17 May 2023 by ‘judge’ Anatoly Solin and two colleagues from the Military court of appeal in Vlasikha (Moscow region).