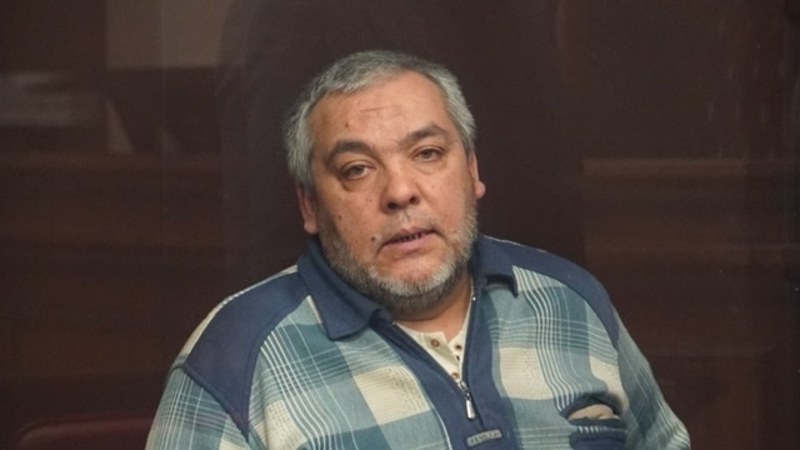

The Southern District Military Court in Rostov (Russia) has sentenced Yashar Shikhametov to eleven years’ imprisonment on the basis of flawed charges, planted religious literature and anonymous ‘witnesses’ who had quite likely never set eyes on him. The 52-year-old Crimean Tatar is in extremely poor health, with chronic high blood pressure causing heart, stomach, liver and spinal problems. He would be unlikely to survive even the first four years of the sentence, in a prison, the very worst of Russia’s penal institutions, let alone the remainder of the 11-year sentence to be spent in a harsh-regime prison colony thousands of kilometres from his family in Crimea.

Shikhametov’s medical issues meant that a number of hearings needed to be adjourned. They also made him unable to speak during the final, ‘debate’, part of the hearings, with presiding judge Alexei Magomadov falsely claiming that Shikhametov had “voluntarily renounced his right to speak.” Shikhametov had planned, in his address, to say the following: “Did we really have a choice in 2014? I will tell you that it’s all true: we are Crimean Tatars by nationality; our religion and culture is Islam; and we are citizens of Ukraine. Is that proof of my guilt? We are not in hiding, we do not conceal that and openly speak of it everywhere. Is that really a crime? All is fabricated by an FSB investigator out of conversations in the kitchen, with searches for intimidation and tormenting people.”

Shikhametov is from Orlinoye on the outskirts of occupied Sevastopol. He earlier appeared as a defence witness in the political trial of Enver Seitosmanov, which may have been the reason that the Russian FSB turned their attention to him. They added him, six years after the earlier arrests in 2015, to Russia’s first conveyor belt ‘trial’ of Crimean Muslims on charges of involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir. The latter is a peaceful, transnational Muslim organization which is legal in Ukraine, and which is not known to have committed any acts of terrorism anywhere in the world. Russia’s prosecutions, under ‘terrorism’ legislation, are based solely on an extremely secretive Russian Supreme Court ruling from February 2003, which declared the organization ‘terrorist’ without providing any grounds or explanation. Russia is increasingly using these charges as a weapon against Crimean Tatar civic activists and journalists, with men who have committed no recognizable crime being sentenced to up to 20 years’ imprisonment. The charges are a favourite with the FSB and their decision to arrest any particular person is a near 100% guarantee that their victim will be imprisoned and receive a huge sentence.

Shikhametov was charged under Article 205.5 § 2 of Russia’s criminal code with ‘involvement’ in a Hizb ut-Tahrir group. This was seemingly the same fictitious ‘group’ which the FSB claimed that Ruslan Zeytullaev had ‘organized’ (a more serious charge) and that Ferat Saifullaevy; Yury Primov and Rustem Vaitov were supposed to have been members of. Russia was still ‘testing the ground’ (and international reaction) in that case and all of the men initially received much lower sentences than required by legislation. The prosecution (or, more likely, the FSB) challenged the sentence against Zeytullaev until they got a 15-year sentence but did not appeal against the other three sentences (more details here). One difference now is that the prosecution almost invariably adds the charge (under Article 278) of trying to overthrow the Russian state. This charge is even more nonsensical, as not one of the men has ever been found to have any weapons, but does enable them to increase the sentence.

Both the earlier ‘trials’ and that against Shikhametov were, as the latter said, based on ‘conversations in the kitchen’ on religious and political subjects. These were sent to FSB-loyal ‘experts’ (from the Kazan Inter-regional Centre for Analysis and Assessments) who provide the opinion demanded of them.

Russia’s FSB have, however, discovered that such prosecutions do not go to plan, primarily because of committed lawyers who insist on demonstrating the flawed nature of both the charges and the alleged ‘evidence’. Although the convictions remain essentially predetermined, the men’s lawyers, as well as the important Crimean Solidarity human rights initiative, provide important publicity about the shocking methods used to fabricate huge sentences.

Armed and masked enforcement officers burst into Shikhametov’s home on 17 February 2021 and carried out ‘a search’, before taking the father of three away and imprisoning him. As in all such cases, lawyers were illegally prevented from being present. The officers claimed to have found three ‘prohibited religious books’. The books, which did not have any fingerprints on them, were in a cupboard holding coats and shoes which was a place, as Shikhametov himself told the court, that no practising Muslim would hold religious literature.

During one of the hearings, Shikhametov stated that he considered the real criminals to be those who planted ‘prohibited books’ in his home. Typically, the only outcome of this was that Shikhametov himself was removed from the ‘courtroom’. Shikhametov has been open in calling those involved in this prosecution and others “accomplices and criminals” and this was not the only time he was removed from the courtroom.

In July 2021, the FSB carried out an armed search and interrogation of Ferat Saifullayev (who had been released after serving his sentence). They threatened “to come back and find prohibited literature” if he did not give false testimony against Yashar Shikhametov. During this interrogation, he was neither informed of his rights, nor told what his status (suspect, witness, etc.) was. Saifullayev signed the document thrust in front of him, but later stated publicly that he had only done so because of the pressure and threats against him. He insisted that this supposed ‘testimony’ should be excluded as having been obtained with infringements of the law and issued a formal complaint to the FSB in Sevastopol, naming senior ‘investigator’ Yury Andreyev.

Prosecutor Sergei Aidinov was never able to explain how Shikhametov, working as a café chef was supposed to have ‘carried out ideological work’ or what such ‘work’ was.

All of this was ignored by presiding judge Alexei Magamadov, together with Kirill Krivtsov and V.Y. Tsybulik who actively took the side of the prosecution. Such bias was seen here, as in all other political trials of Crimean Tatars and other Ukrainians, in the use of ‘secret witnesses’. The only real ‘evidence’ in this ‘trial’ came from people whose identity was not known, and whose supposed testimony could not be verified. In all these trials, the judges invariably disallow questions aimed at demonstrating that the person is lying and that he does not in fact even know the defendant.

Please write to Yashar Shikhametov!

He will almost certainly remain imprisoned in Rostov until his appeal hearing. Letters tell him that he is not forgotten and send an important message to Moscow that their persecution of Crimean Tatars and other Ukrainian political prisoners is under scrutiny.

Letters need to be in Russian, and on ‘safe’ subjects. If that is a problem, use the sample letter below (copying it by hand), perhaps adding a picture or photo. Do add a return address so that the men can answer.

The addresses below can be written in either Russian or in English transcription. The particular addressee’s name and year of birth need to be given.

Sample letter

Привет,

Желаю Вам здоровья, мужества и терпения, надеюсь на скорое освобождение. Простите, что мало пишу – мне трудно писать по-русски, но мы все о Вас помним.

[Hi. I wish you good health, courage and patience and hope that you will soon be released. I’m sorry that this letter is short – it’s hard for me to write in Russian., but you are not forgotten. ]

Address

344022, Россия, Ростов-на-Дону, ул. Максима Горького, 219 СИЗО-1.

Шихаметову, Яшару Рустемовичу, г.р. 1970

[In English: 344022 Russian Federation, Rostov on the Don, 219 Maxim Gorky St, SIZO-1

Shikhametov, Yashar Rustemovich, b. 1970 ]