Dreams shattered

My name is Maria Vdovichenko. Before the war, I was supposed to finish 11th grade. I was already preparing for EIT (External Independent Assessment) and graduation. My classmates and I picked shoes and fabrics for future prom dresses. I was also the President of School No. 54. I was interested in scientific activities and wrote several scientific works in history and international law. I studied these subjects and continue to take an interest in them. I was also the first bandura player in the city of Mariupol at the OCU temple. I love my culture very much, so most of my projects aimed at popularizing the Ukrainian language and culture.

The first thing I remember is how, on 24 February, my mother burst into the room and shouted loudly and hysterically, “The war has begun! Let’s go!” Mom did not sleep that night; she heard the first explosions and was very scared. Until the last moment we did not believe the war was possible and, on the twenty-fourth, it was terrible to realize: is it really true? When the shelling of the Vostochny began, our Primorsky district was already shuddering and our house was shaking, this make me realize, “Yes, this is a real war.”

Panic broke out both in neighboring apartments and throughout the city. At four in the morning people began to gather in shops, buying up everything that could be bought. Of course, shops were robbed because many people had no money, but there was also a panic. There were crazy queues at gas stations, and traffic jams at the exit from the city. It was already noon by the time my family was more or less assembled. We thought about leaving, but our neighbors returned and said, “We can’t leave anymore, the city is closed, active hostilities are going on near the city. It’s not safe to leave, you can go straight into the battlefield.” Then we started looking for a shelter, because we understood that everything would really happen to us and our homes in a little while. That said, we didn't realize yet how serious this could be and when we heard strange sounds, we hid in the bathroom and the corridor, because there were no bomb shelters nearby.

In such a way we lived until the beginning of March. Then, our electricity and water were turned off, there was no heating, communication was intermittent and later it disappeared altogether. We found ourselves in an information vacuum. There were no supplies to shops in the city, medicines were running out in pharmacies, shopping centers were smashed, and everything was looted. There was already a blockade, the city was closed, and we were left with what we had. We did not make any stocks: no water, no food.

We ate once a day to conserve our reserves as much as possible. We extractd water from snow and rain, or looked for streams, because there was no place to buy water. We led such diminished life until the second of March.

We managed to eat tolerably well, but didn’t sleep well at night, because there was uncertainty, an information vacuum, no one communicated with us, and there was constant chaotic movement in the city. Our house was not just bouncing endlessly, but vibrating with terrible force. One day everything around us began to fall and the glass burst. We abruptly rushed to the bathroom: me, mom, dad, and my sister, we even took the cat with us. As soon as we settled down, we felt a terrible blast wave, we were nailed down by it. What does it mean "to be nailed by an explosive wave"? You can't hear anything, there is buzzing in your ears, you can't see anything because the plaster is falling from the ceiling. We did not know whether the stairs were intact, how to get out, or where to run. There was a crazy panic. We began to gather, get dressed in the first things we could find in order to run to the basement. The fifth floor was badly broken, but we lived on the third floor. A little longer — it would have reached us. However, my mother could not walk, because she suffered from polyneuropathy for six years. We carried her to the basement and my sister took the cat and ran ahead of us. It was cold outside, there was snow on the ground and ice was powdered with glass from shelling. The wreckage of the house was falling apart, cars were burning nearby as we escaped towards the basement.

First, my sister knocked on the cellar door, but no one opened it for us. Dad started knocking so hard that the people inside decided to open the door for us, but when the man opened the door, he said, “We can’t let you in, there are already many people here.” However, my dad did not listen to him as shells exploded above, us and it was unsafe to wait outside. Dad pushed him away; we broke in by force and found our neighbors there who had been hiding for several days. The shelling was very strong. There was nothing in the basement: no food, no water. The next day, together with other people, we decided to take things from the apartments. My dad and I went up together so that I could help him pack things. To get into the house, we had to go around the fence. While we were passing, shelling began again. Dad fell to the ground, grabbed me, and we lay behind a stone slab. I tried to get up, but dad said, “Cover your head so that nothing hits it, lie down and don’t twitch.”

I got scared and tried to raise my head, I saw about 40-50 meters from us the silhouette of a person. I didn't know if it was a woman or a man. There was a human being, and the body was torn apart in an instant. Instead of a human, there were bloody pieces of flesh in the air and on the pavement. It was not just a shock, I could not understand how it was possible...

It was then that I realized that my dad pressed me to the ground with his palm so that I would not look at it, and he did it not just for security reasons. When the shelling moved to other streets, we ran to the entrance and hurriedly collected things. We grabbed everything we could hang on ourselves, and went down to the basement. That day people tried to cook. They put some kind of cauldrons, and saucepans on the fire, because we had no gas, but the shelling began again. It was so strong that we were thrown from wall to wall in the basement. Fragments of the ceiling were falling, people were screaming, children were crying. At that time, I realized that I was still alive, but I was slowly dying. I felt almost dead, both physically and emotionally. Everything seemed to keep falling on us, a little more and we would all just burn because it was very hot. As it turned out later, my room was hit during that heavy shelling.

Life under shelling

We initially had some canned food and bread, but everything ended quickly. Later there were times when we did not even have water. In Mariupol, standing in line for a water was very unsafe, because of the shelling, shrapnel, and random fire. It was unclear who was shooting people and for what, but there were victims. Of course, people were afraid to stand in these queues, because you don’t know what could happen in a split second. Near our house was a park with water springs, but someone mined them. Since we were in a complete information vacuum, we did not know who was mining, but there was a case when two people were torn apart, they were simply trying to draw water from a source.

Another person was so crippled that someone simply finished him off, so he would not suffer. It was impossible to take him to a doctor or call a doctor, because there was no longer the medical care we had before the war. No ambulances, you would have to go to the hospital yourself. The nearest hospital was in the Central District and it was impossible to get there.

My family also faced a lack of medical care. Mom was getting worse, because in the basement we couldn’t sleep properly, we didn’t have food, we were starving, there was no water and fresh air, rats were running around, the ceiling was crumbling from constant shelling, the house was being destroyed. It was scary ... At first, she had problems with breathing, and one night, when the whole family was lying on the same blanket, dad realized that her body was cold and she was not breathing. He desperately began to massage her heart trying to provide artificial respiration. I saw despair in his eyes. I was frightened then: I understood how serious it was, she could die. My mother’s cold hand was in my hand ... I realized that because of someone’s ambitions, the desire to win, I could lose in that basement a loved one due to the lack of medical care. It was very difficult for healthy adult men, some jumped out of windows unable to face it all. I was very afraid of losing my family. There was no medical assistance and none of the neighbors in the basement offered to help dad. Finally, he did what he could for her, he started her heart and she began to barely breathe. There were nights when we already knew how the shelling would go. We knew the schedule, but when the situation escalated, there was a feeling that the trains were going in different directions right above our basement. The vibration was so strong. So many neighboring houses were destroyed with people buried inside.

The Primorsky district was seemingly hidden from all this, but it was also severely mutilated. The video shows that everything survived there, but this is not true. Our house was almost destroyed, only an empty skeleton was left. At that time, I was sure that we would all die. You lie at night and just pray: “Well, if I die, Lord, give me an easy death. I do not want to suffer; I do not want to see others suffer.” The worst thing is to die alive, to understand that the basement is covered up, there is no help and people will not remove the rubble with their bare hands.

In such way we lived until 17 March. We sat there all blackened and filthy, there was no air to breathe in the basement. Dad decided that we should go anywhere, because staying was pointless . We all understood: sooner or later the house would collapse, or someone would find us in the basement, because basements were set on fire, bombarded with explosives, and people burned alive. Various terrible things happened then. Now I understand that there were Russian soldiers who were throwing noise bombs to lure people to the surface, they looked for certain people and also girls. They drove tanks into the lyceum looking for young girls to have fun, they felt like winners, they needed company of young girls. There were such cases of mistreatment in Mariupol. We cannot say we were lucky, but we were lucky to not become victims of all this. Dad got the news from the residents of the neighboring basements that it was possible to go to Melekino. On March 17, we decided to pack up: we took the remains of things from the basement, because the apartment burned down and there was nothing to take away from there. While we were driving around the city, we saw burnt equipment, destroyed houses and corpses. It was all on the street.

Exiles in New Yalta

When we arrived to Melekino, there was a DPR ( Donetsk People's Republic) checkpoint. They could be easily recognized by their chevrons, ribbons on their arms, and uniforms. We were asked what kind of registration we had. If it is Mariupol, then our road is to the right. Dad tried to persuade them that we need to go to Melekino as we have relatives there, but they simply pointed weapons at him and said: “You can stay here if you don’t want to go.” Dad silently got into the car, and we drove along that road. Now, re-reading the news, I know we were driving on a booby-trapped road. Nobody told us about it, we were simply sent there whether we survive or not. That road led us to Mangush. A huge number of cars gathered in Mangush as well as people who walked; there were a lot of DPR soldiers. It was no longer possible to move forward or backward, we just stood and waited. Nearby there were shelling, screams, explosions and panic. Finally, we turned onto a road which led, as it turned out later, to New Yalta. The roads were unfamiliar, we didn't know where we were going. When we entered New Yalta, it was already impossible to go back, they changed city’s authority in Mangush, appointed their police, and carried out a cleansing operation precisely because many people there held Mariupol residence permit.

The military of the DPR went from house to house, checking people’s belongings, what kind of symbols their tableware had and how they spoke. They stopped people on the street, asked questions, there were cases when they did not like a person, so they would wring their hands, take them away in an unknown direction and these people would disappear. In New Yalta, we found a shelter boarding with an old, abandoned pensioner. Unfortunately, we did not have money or valuables to exchange to rent a normal accommodation.

There was a well in the yard of this pensioner’s house, and this water was a treasure for me. We could boil it, drink it, wash our faces and hands, it was like a holiday. However, there was no humanitarian aid. The invaders said, “You can come to certain places and provide your personal data to be registered and receive dry rations.” As it turned out, they registered refugees, but did not give these rations to any Mariupol residents. Instead, they were handed out to residents who could buy at least some food, and we were sitting with nothing.

There were several hundred left in my father's pocket, they were only enough for two loaves of bread and that was it. There was a shortage of food in New Yalta, because the food was imported from the Russian Federation and only to two stores, so the queues there were just crazy. Of course, it was difficult to buy something, because the prices were high. When dad went for bread, I went with him. It was difficult for me to let him go alone, because the military constantly pestered somebody. When we were standing in line for bread, I accidentally stepped on a woman’s foot and said in Ukrainian, “I beg your pardon, I’m sorry.” And she slapped me on the face for the words spoken in Ukrainian. After that, dad told me that I should not go out, it is better to be silent and not to show anything. Being there, of course, was difficult. And again, we experienced cold, hunger and lack of medical care.

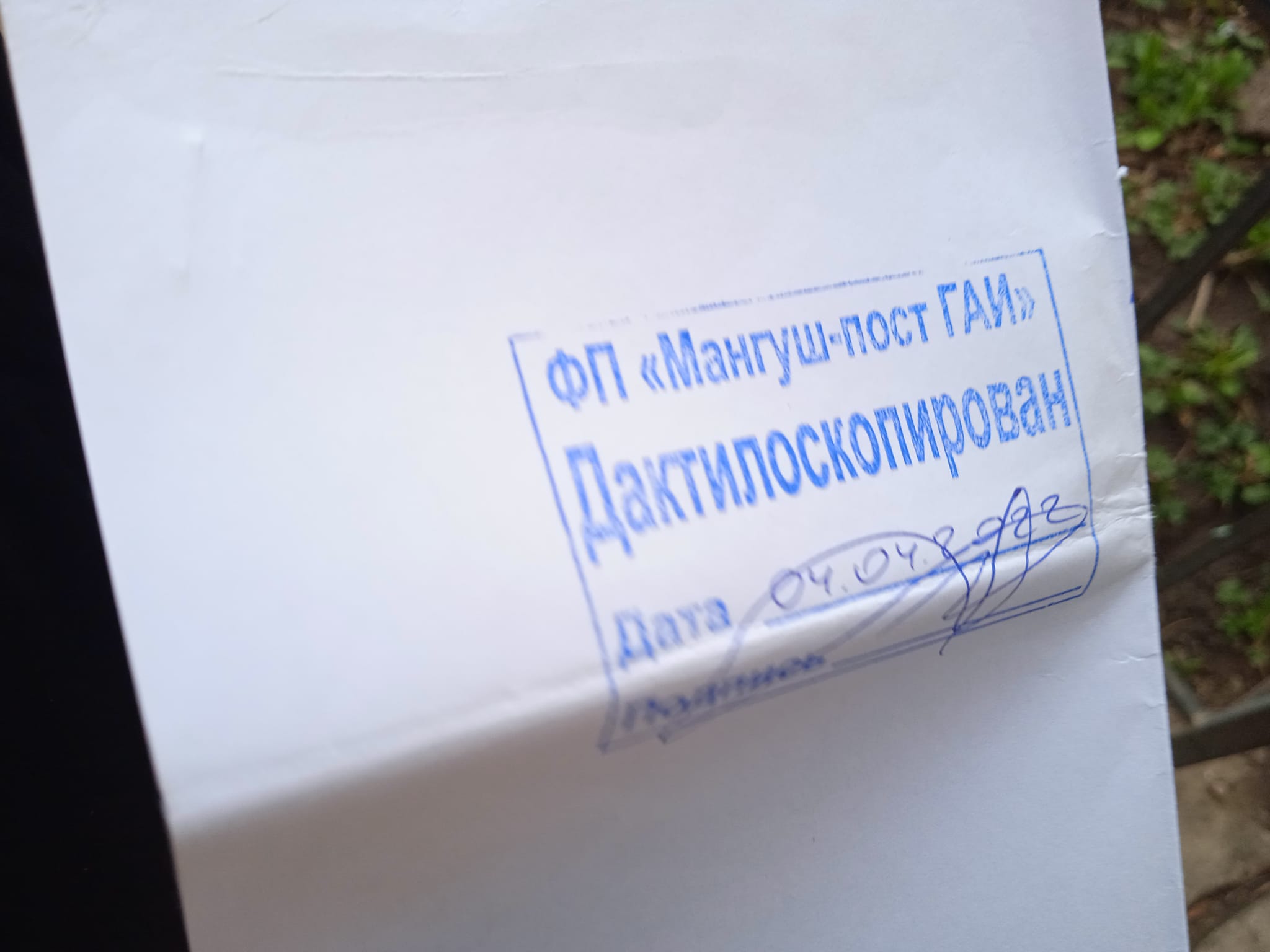

We suffered in the city of New Yalta for twenty days. Dad found out from people on the street that it was possible to go through filtering. Initially, they simply scan documents, take pictures and fingerprints, and later let people go. They were giving certificates with which people could move around the territory of the Russian Federation. There were rumors that the Ukrainian territory was occupied, and to get there, one also had to go through a filtering process. Without further thought, we packed up and went to the filtration site. When we arrived at the first checkpoint, they showed where to go. There was only one way to get through that process. We had to return to Mangush and wait in line. Vehicles with the letter “z” were constantly driving past us, they brought their journalists who filmed our queue.

People were standing in line waiting for something, but they presented it as if they were saving them and organizing humanitarian corridor.

It was difficult for us in this queue, because we spent two days and two nights just sitting in the car. It was impossible to leave. When we tried, the military interfered: they asked why we were leaving and for what purpose, they searched us, examined what we were doing in the car, and said that we should stay in the car, “Just wait in the car.” For us, this was additional problem as our Zhiguli is a small car, and there were four of us and a cat.

Filtering, humiliation, and threats

We were launched for filtration at eleven o'clock at night. It was like a checkpoint where they checked everything: documents and all belongings. Then a man approached us and said that filtration starts at the age of fourteen. My sister is twelve, she was too young for this, and my mother at that time could not walk. We were very lucky that they did not want to mess with her. Dad and I were taken to a filtration booth two hundred meters from the car. We stood in line and waited. The night was cold, there was snow on the ground, but we were standing and waiting, because the DPR people were having dinner. While they had dinner, smoked, and talked, we just stood on the street and waited. It would be difficult to forget this atmosphere: how they talked to each other, laughed. It was very difficult to get into my head that some of their phrases could have been jokes. You are standing there, you hear screams, shots and you think, “Why is someone screaming?” And then the phrases, “What did you do with those you didn’t like?” “I shot and didn’t think!”

Next to us in line was a young woman who left a small child in the car. The boy was screaming because it was night, strange noises, soldiers with weapons were walking nearby, and he was alone. He shouted and the military who passed by this car did not like it, they knocked on the door and tried to shut him up. Of course, the child was scared, he squealed even more, but the mother was not allowed near the car to calm the child, sit with him, or take him with her.

The filtration began again, a man and his wife entered in front of us, then he came out and asked, “How long do I have to wait for my wife at the exit?” They answered him, “Which wife? She didn't pass. You go alone”. I do not know what happened next with this man, because it was our turn. They processed two people. Dad and I went in, he was taken into the next room, and I stayed in the first one. At first, I was very scared, but I tried to calm myself. They asked me for documents, scanned them, then took my fingerprints. It did not work at first because my hands were shaking very badly. The inspector yelled at me, grabbed my hand, and pressed my fingers. I had to endure it, because I understood that I had to somehow pull myself together, there was no other way out. Then they checked my phone, but my whole family decided to erase everything from the phones while we were still waiting in line. We understood that they were looking for nationalists, fascists, people with pro-Ukrainian views, and we had photos in embroidered shirts, photos with flags. We are Ukrainians, a separate nation, we have our culture and this is normal. We could have been killed or mocked for it, so we decided to remove all.

I left a half-empty account on my phone in which there was nothing provocative: some homework and inconspicuous things. I also made several portraits, photographs of my cat, and in the notes, there were some drawings, so the empty gallery would not seem suspicious. The parents' phones were completely empty. Dad paid the price for this, but more on that later. There was nothing provocative in my phone, and it was returned to me. When the interrogation began, the inspector took my passport, checked the information, and asked me how old I was. I replied that I was seventeen. When he heard this, he looked at the passport, then at me and laughed, “How are you seventeen?” Then they started laughing, joking about how stupid I am, undeveloped by the age of seventeen, what a childish face I have and how I am still a child. They vigorously discussed that there would be more girls later, that the previous one was more beautiful, and I stood there not understanding, “What are they talking about?”

So, jokingly, they wrote me a document indicating that I passed filtration. There was a seal, a date, surname, and initials. I took my passport and documents, checked everything, because I was afraid to forget something. On the way out, they pushed me in the back. I was humiliated, but okay, this kick was supposed to be the end of my torment, however the one who pushed me, followed me, and then pulled me towards the cars.

He pushed me forward and backward like a kitten, but I did not understand why he was doing it. I feared he would turn me in the other direction, not towards our car. Instead, he kept pushing me until I fell. When I fell, he laughed.

I did not waste time thinking about it, but simply got up and quickly ran to our car, I flew into it, sat down, and waited for what would happen next. Then, my mother and sister asked, “Where is dad? How long we have to wait? What was there?” I just sat there in shock and waited, because I did not know what to answer.

Later dad told us what happened to him. They also took his documents and fingerprinted him. Since he was a man, he was undressed, his whole body was examined for tattoos, his phone was checked and he was interrogated simultaneously. During interrogation, he was asked how he served in the military at the age of eighteen, who he was, whether he served again, whether he was related to the ATO (Antiterrorists Operations), how he feels about Ukraine, who he works for, and what plans he has for the future. Questions could be anything. Of course, when they asked something about Ukraine, they humiliated our Motherland in their questions, suggested what they would like to hear in response, they also tried to knock out some information from him. The father tried to give neutral answers despite the pressure from several military men with weapons. They pushed him, pulled his clothes, and poked him with a weapon. That is, they did it so that his attention was scattered and the answers were unconscious. When they realized his phone was empty, the first question was, “Do you think we are completely stupid? Do you want to deceive us? Do you think we are some kind of idiots? They started pushing him hard, asking, “Are you a fascist? Are you hiding a swastika there?” Finally, there was a question, “What will you say if I cut off your ear?”

Dad gave neutral answers, he held on to the last, until he was hit with something heavy on the back of the head. After the impact, he fell and was simply lost in reality: he did not understand what was happening.

Since nothing was knocked out of him, he was given a document that he had passed the filtration. Papa returned to us with a shaky gait, and we did not realize what had happened to him. He said nothing on the spot. The DPR military said, “You have to move on.” At night, during the curfew, there was only one road to Berdyansk. We were driving at night without lights, because if we turned on the lights, the car could be seen and shot at. On the way, we saw burnt equipment, destroyed houses, charred remains of people in cars. I saw it as something unrealistic. Dad almost crashed the car several times, he bumped into something, and when we drove up to the Russian checkpoint, he almost crashed into a stone fence, because usually there are obstacles at the entrance to slow cars down. At the checkpoint, we were searched again, they checked everything and asked for filtration documents and the phones. Dad's phone, of course, remained empty. The military pulled dad out of the car and started pushing him asking, “Why is it empty? What are you hiding?” But he was distracted by other Russian military men. They discussed the women they tortured: what they did to them, their fate would be and what to do with them now.

Road to survival

Without much hesitation my dad jumped into the car, and we drove at high speed to Berdyansk. In Berdyansk, we dozed a little and calmed down. At dawn, we drove towards the city exit in the direction of Zaporozhye and there we stopped in another queue of cars. People were waiting for the day light to leave, because of the broken roads, there may be battles ahead, or other obstacles. It was important to be able to see what was happening around. Some people hoped to chance upon buses. After talking with most of them, dad realized that it was useless to wait, we had to go. The road was broken, the column of cars was disorganized. It was survival on the road, because we were passing through villages where real battles were going on, there were twenty-seven block posts near Zaporozhye where anything could have happened to us. We met a woman in Zaporozhye traveling with her husband and children. The husband was detained because they did not like him and he aroused suspicion. The family was forced to move on because they were threatened to be shot on the spot. She took the children and went but lost contact with her husband.

I saw how they spoke to my father, he was told, “Why do you need this Ukraine? Come and join our ranks!” I do not know how he could carry on and find the right words of refusal. At such moments, dad would say that he was sick, he felt bad. Indeed, after the beating in the filtration camp, he was very sick, he felt nauseous and dizzy. He reacted inadequately to everything, but tried to hold on. At most roadblocks, dad, like other men, was stripped right on the street to check if he had tattoos. Men were checked very carefully everywhere, they were not only asked questions, but also pressured: “You are a military man, I can see it by your looks!” At some roadblocks, they even disturbed us about my cat, I did not understand why they needed it, but they said, “Give me a cat!” I was afraid that someone would let my little animal go as a joke, she would get scared and we would not find her, or they would just twist her head in front of my eyes. It was difficult to bear all this. It was difficult to drive through a mined field, along a mined road. The worst thing was when we saw a mine and could not believe it. Well, it can't be! I would say, “Mom, there is a mine!” And she would say, “Where?” My sister also saw mines, but the father did not. On the way, his eyesight began to fail, he was getting worse, but he held on. He had to slow down because we understood: if one driver makes a mistake, everyone else will suffer.

The gray zone was also not very easy, because shots sounded, mines again, unexploded shells, crumpled cars. We just tried to go despite everything, because we realized - a little more, and we will be on land. When we saw the yellow-blue flag in the distance, I felt better: a bit more, and there will be a small victory for us. But dad was full of distrust and saw a catch in everything. He said that this could be a test for nationalists, we should not show any emotions, we should keep quiet and see how it will turn out. It was already near Zaporozhye. We drove up to the checkpoint, where they asked for our documents in Ukrainian. They saw that the windshield wiper flew off, the tire was half-flat, and they tried to lighten the atmosphere a little and joked. We examined their chevrons and realized that these were our people. Finally, the long-awaited relief has arrived! Of course, there were tears and violent emotions. They helped to repair the tire, offered water, and sent us to a convoy formed by the police. And so, accompanied by the police, with our fellow refugees, we went to Zaporozhye.

From Zaporozhye to Western Ukraine

In Zaporozhye we were fed. I will never forget that delicious coffee in which sugar and cream were plentiful. Probably the most delicious and most desired coffee in my life, which I so dreamed about during the occupation. Dad and mom were given medical assistance, they gave us a sedative, because we were all nervous and cried all the time. Mom was put on several drips so that she could walk, because polyneuropathy is a chronic disease. She used to take medications regularly and every six month had some courses of drippers which is necessary to maintain her body. When the blockade and complete occupation began, none of this was possible and she was getting worse. The doctor who treated her there was a real professional in his field, and prescribed her effective drugs. Papa was also given painkillers; they examined the consequences of beatings. His eyesight began to deteriorate. The doctors couldn't explain why. There was a suspicion that it was a contusion, but it was necessary to complete examine the head to understand what was happening to him. We were sent with volunteers to the city of Dnipro where a special commission, led by the head of the ophthalmology department, carried out a serious examination. They concluded that he had an atrophy of the optic nerves as a result of concussion. He was hit on the head very hard. The doctors warned him about the consequences, his body was exhausted by the war both physically and psychologically. They said he needed a treatment.

We were sent to Western Ukraine to see a doctor who specializes in that field and could help us. There were some difficulties, but we found volunteers who helped us search for specific drugs and raised money for treatment. Unfortunately, the drugs were expensive, and we left with nothing. The treatment had started, but the father's condition did not improve as it takes not month or two to get better. It may take several years. The optic nerve atrophy continued and my dad could not see anything. We could not stay in Lviv for a long time due to the huge queues of refugees and many wounded in hospitals. Finally, we were sent to the city of Sambir. There were shorter queues, they conducted another examination, the same diagnosis was pronounced and the treatment began anew.

New threats and travel abroad

When we were in Sambir, strange e-mails, calls, notifications in Telegram and Instagram began to come to me. They wrote: “So, Khokhlushka [Russian derogatory or insulting nickname for Ukrainians], what are you doing? Ask for forgiveness!” I did not understand why everyone was writing to me, what kind of threats they were making, and what was happening in general. I saw tricolors on the avatars of people who wrote to me, and I did not understand who they were. Finally, I asked one person, “Why are you writing this to me? What do you want from me?”

They sent me a story from the Rossiya24 TV channel, where they had my picture in an embroidered shirt with a bandura and the caption, “The new face of Kyiv propaganda. She slanders our military. Russian soldiers could not beat an elderly man, the father of children, they could not offend a child, destroy houses, or mock people. We are saints here, and the entire country [Ukraine] is playing war.”

In the following issues, they claimed that I was an adult woman who impersonates a teenager, they came up with children for me, some family photos. I looked at all this and thought, “Well, next they will show my photo with a swastika.” It was absurd, it was ridiculous. I could not believe how hundreds of people trusted it. In my Telegram, I had a hundred chats where I was humiliated and threatened. They had such a goal: if we cannot destroy her physically, we must finish off her family morally so that none of the freaks survive. There were specific threats to our address in Lviv. These people tried to find me while we stayed in Lviv.

We realized that it was no longer safe to stay in Ukraine. In addition, the doctors said that if their treatment method did not help soon, my dad could lose his sight forever. It was necessary to go abroad, because he had an opportunity to recover there. For these two reasons, we decided to go further, abroad. We asked for help from volunteers, because, unfortunately, after the war started, we were left with nothing. We asked for help around the world and eventually moved to a country where we stay now. We have a house, but there are problems with the treatment, and health comes first for us. Insurance covers everything, but dad's ophthalmology issue is a narrow specific problem. Treatment is expensive and long, and it is difficult for us. We want to return to normal life in Ukraine again, but we understand that first we need to solve these health problems. We will overcome everything. We are confident that we will win. Everything will be Ukraine again. I want to make a significant contribution to the development of our country, because people from Ukraine have helped us and continue helping us morally, financially and with kind words, so I must thank my Motherland. Unquestionably, I want to be helpful. It's probably not just a dream, but a goal that can be realized over time.