32 countries have thus far joined Ukraine’s application to the UN’s International Court of Justice [ICJ] against the Russian Federation. Although Ukraine’s initial application, within two days of Russia’s full-scale invasion, specifically addressed Russia’s spurious allegation that Ukraine was guilty of ‘genocide’ as excuse for the invasion, there are also serious grounds for accusing Russia of genocide over its war against Ukraine.

According to the ICJ decision from 9 June 2023, 32 countries’ applications have been found admissible. These include all EU member states, except Hungary; the United Kingdom; Canada and Australia. ICJ did, however, reject the application to join from the USA on the grounds that the latter had not accepted part of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide [the Convention on Genocide], when it signed the rest.

Ukraine lodged its application against the Russian Federation on 26 February 2022. It asserted that Russia was violating the Convention on Genocide by making false claims as justification for its war of aggression against Ukraine. In the early hours of 24 February 2022, Russian president Vladimir Putin announced what he called a ‘special military operation’. He claimed that this ‘operation’s’ objective is “to protect people who have been subjected to bullying and genocide over the last eight years. And for this we will seek the demilitarisation and denazification of Ukraine.”

All of these claims were dismissed from the outset as baseless, with this reflected in the relative speed with which the International Criminal Court [ICC] also became involved. By 25 February 2022, ICC Chief Prosecutor Karim Khan had said that the Court was closely following events and might investigate possible war crimes. He suggested then that an investigation could be expedited if member states were to apply for such involvement. By 3 March, 38 countries had responded, asking ICC to investigate Russia’s indiscriminate bombing and other war crimes.

In its application to the International Court of Justice, Ukraine specifically asked for the Court to impose provisional methods, ordering Russia to stop its attack on Ukraine.

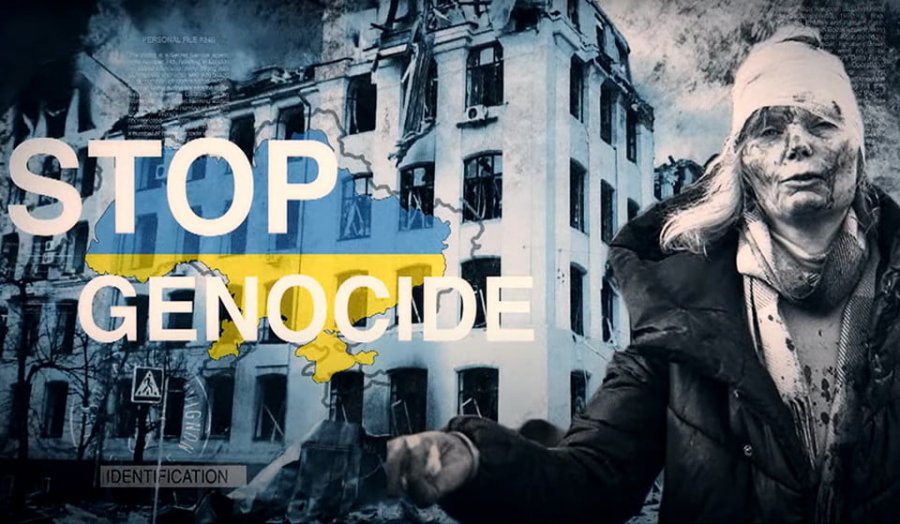

This ICJ did, ordering Russia to immediately suspend all military operations in Ukraine. That order, however, came on 16 March an hour or so after Russia had committed one of its bloodiest war crimes to date, namely the bombing of the Drama Theatre in Mariupol. Despite clear signs, in Russian, around the building that there were children inside, Russia dropped two powerful bombs on a building where over a thousand people, mainly women, children and the elderly, had hoped to find shelter from the Russian onslaught. It is believed that at least 300 civilians were killed.

The ICJ’s orders are, in theory, binding, but the Court has no mechanisms for compelling a country to comply with them. Russia has ignored this order, as it did the provisional measures imposed by ICJ in a separate case brought by Ukraine on 19 April 2017.

Even without mechanisms for implementation, these cases and eventual rulings from international courts are important. Russia has reacted to all such inter-state cases by claiming that the courts themselves do not have jurisdiction. After initially ignoring the proceedings, it took part to the extent of claiming that ICJ should dismiss the case since, it alleged, the Convention does not cover the use of force between states. There is nothing to suggest that the Court has taken this allegation seriously.

The weight of evidence against Russia has increased substantially since the application was first lodged, with the grounds for accusing Russia itself of genocide hopefully also becoming part of the proceedings.

In May 2022, an independent report by recognized human rights lawyers and scholars warned of a serious risk of Russian genocide in Ukraine and stated unequivocally that this “triggers the legal obligation of all states to prevent genocide.” A detailed analysis was provided of Russia’s “direct and public incitement to commit genocide, as well as of “a pattern of atrocities from which an inference of intent to destroy the Ukrainian national group in part can be drawn.” The authors looked, for example, at the constant denial by high-ranking Russian officials and the state media of the very existence of a separate Ukrainian identity; and at repeated incitement to genocide, with Russia trying to justify this through the false claim that Ukraine had committed genocide in the Russian proxy Donbas ‘republics’ (more details here). Within a month of the report’s publication, former [nominal] Russian president Dmitry Medvedev very publicly expressed ‘doubt’ that Ukraine would still exist within two years.

Other examples of the Russian state media’s “direct and public incitement to genocide” against Ukraine can be found here.

In March 2023, the International Criminal Court issued its first-ever arrest warrant against an acting head of state. Karim Khan stated that warrants had been issued against Putin and his so-called ‘commissioner on children’s rights’ Maria Lvova-Belova given “reasonable grounds” to believe that both those individuals bear criminal responsibility for the unlawful deportation and transfer of Ukrainian children from occupied parts of Ukraine to the Russian Federation.

The deportation of children is not only a war crime but can constitute both a crime against humanity and an act of genocide. In defining “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group,” the above-mentioned Convention on the Prevention of Genocide specifically names “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.” [Article II(e)].

The eventual ICC indictment remains to be seen, however it is worth stressing that Russia is not concealing, nor has it concealed since 2014, its aim to turn Ukrainian children into ‘Russians’. On all areas that fall under its occupation, Russia moves swiftly to try to indoctrinate children into believing that they are Russian and, essentially, that all Ukrainians who think otherwise are ‘the enemy’.