Russia’s ‘trials’ of Crimean Tatar political prisoners are always based on fabricated evidence and flawed charges, yet the level of fabrication used to pass 13-year sentences against Oleh Fedorov and Ernest Ibragimov was breathtaking. The men were charged on the basis of an innocuous conversation which Fedorov had not taken part in, with effectively the entire case copy-pasted from Russia’s internationally condemned attack on Crimean Tatar human rights activists four years earlier.

It seems likely that ‘judges’ Oleg Yegorov; Sergei Butusov and Anatoly Solin from the Military Court of Appeal in Vlasikha (Moscow region) had already issued their ‘ruling’ on 12 July, as they made no pretence of considering evidence regarding gross discrepancies in the phonographic ‘expert assessment’, an almost certainly deliberate ‘mistake’ in translation from Crimean Tatar; proof that the ‘secret witness’ testimony was untrustworthy, as well, of course, as the fact that Fedorov was not on the tape used to imprison him. They ignored all of this, and more, upholding the 13-year harsh-regime sentences against Oleh Fedorov (b. 1970) and Ernest Ibragimov (b. 1980) with the first 3.5 years to be spent in a prison, the very worst of Russia’s penal institutions. Those sentences had been passed on 8 July 2022 by presiding judge Igor Vladimirovich Kostin, together with Roman Konstantinovich Plisko and Aleksei Borisovich Sannikov from the Southern District Military Court in Rostov (Russia). Those same individuals ordered that each of the men, if they survived the sentence, then face a further year of severely restricted liberty.

There is simply no possibility that the ‘judges’ and prosecutor Valery Kuznetsov were unaware of the glaring flaws in the trial of these two men. So too were the FSB officers in occupied Crimea who had first targeted eight Crimean Tatar civic journalists and activists and ensured that they received sentences of up to 19 years for their civic position, and then, four years later, came for Fedorov and Ibragimov. The latter had also spoken out against repression in occupied Crimea and sought to help political prisoners and their families.

Neither Fedorov, nor Ibragimov, was accused of any recognizable crime. The charges against them – of ‘involvement in a terrorist organization’ (Article 205.5 § 1 of Russia’s criminal code) and of ‘planning a violent seizure of power and change in Russia’s constitutional order” (Article 278) were based solely on unproven allegations of involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir. The latter is a peaceful, transnational Muslim organization which is legal in Ukraine, and which is not known to have ever carried out acts of terrorism. The 2003 Russian Supreme Court ruling declaring Hizb ut-Tahrir ‘terrorist’ was issued in secret and kept from the organization itself and human rights groups under it could no longer be appealed against, and was, almost certainly, politically motivated.

In occupied Crimea, Russia is using these Hizb ut-Tahrir prosecutions as a weapon aimed at crushing the Crimean Tatar human rights movement, especially civic journalists and activists from Crimean Solidarity.

The cynicism of Russia’s use of ‘terrorism’ legislation is particularly highlighted in this case since Fedorov and Ibragimov were only arrested on 17 February 2021, although everything about the charges and the ‘evidence’ was essentially a remake of the ‘case’ against eight civic journalists and activists arrested back in October 2017 and May 2018. Crimean Solidarity Coordinator and civic journalist Server Mustafayev; four other civic journalists Marlen Asanov; Ernes Ametov; Timur Ibragimov and Seiran Saliyev, as well as two civic activists Memet Belyalov and Server Zekiryaev and Edem Smailov are all now serving sentences from 11 to 19 years, although the charges were fatally flawed, and real evidence, even of involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir, non-existent.

Four years later, they used identical charges against Fedorov and Ibragimov. Neither Russian ‘court’ showed any interest in the fact that Oleh Fedorov’s voice was not even on the illicitly taped conversations which are presented as ‘proof’ of involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir. The FSB had mixed him up with another man who has since been arrested himself, Ruslan Murasov.

In all of these prosecutions, the FSB uses ‘expert assessments’ by individuals with no expert knowledge of the subject, but who can be relied upon to claim that this word or that sentiment ‘proves’ support for Hizb ut-Tahrir. During the trial of the eight civic activists and journalists, Dr Yelena Novozhilova, an independent and experienced forensic linguist, gave an absolutely damning assessment of the linguistic analysis produced by the two linguistic ‘experts’ - Yulia Fomina and Yelena Khazimulina, This two was ignored by both first and appeal courts. Both refused to question Murasov who was willing to confirm that it was his voice on the tape, not Fedorov’s, and also ignored the real forensic linguist’s assessment.

The most egregious example of collaboration between the prosecution and court is, however, in the use of so-called secret or anonymous witnesses. No evidence has ever been provided that even one such anonymous witness would be in danger if he testified openly. This is never demanded by the court, which, instead, systematically prevents the defence from asking questions aimed at demonstrating that the supposed witnesses are lying.

In Fedorov and Ibragimov’s trial, as in that of the eight activists and journalists, the identity of two ‘secret witnesses’ was, in fact, known, as were the reasons for believing their testimony to be fundamentally flawed. Ibragimov recognized one of the men, by his manner of speech, as Narzulayev Salakhutdin, a man who was living in occupied Crimea without the proper documents and who categorically did not want to be forcibly returned to his native Uzbekistan. This very clearly gave the FSB leverage over him. Both Fedorov and Ibragimov recognized the ‘secret witness’, under the pseudonym ‘Ismailov’, by his voice (and likely accent). Ibragimov identified him in court, stating that he had known him as ‘Kostya the Latvian’, although he had also been known as Konstantin Alexeyev. This individual’s real name appears to be Konstantin Tumarevich, and he too has taken part in several trials as a secret witness. Just like Salakhutdin, it is clear that Tumarevich was in a very vulnerable legal position, as a fugitive from justice in Latvia, without proper papers.

The three judges from the court of appeal also had a duty to consider whether such ‘witnesses’, whose alleged ‘testimony’ was all that linked the men with Hizb ut-Tahrir, were reliable. They failed to do so, just as they refused to consider the fact that Fedorov’s voice was not on the tapes. The defence was also ignored when they pointed out a serious discrepancy in the translation of an expression in Crimean Tatar. Instead of correctly translating this as “forfeited trust”, it was claimed to mean “knocked out his eye” [!]. The difference is too great to be accidental and was undoubtedly aimed at suggesting that Fedorov and Ibragimov had used force against others.

******************

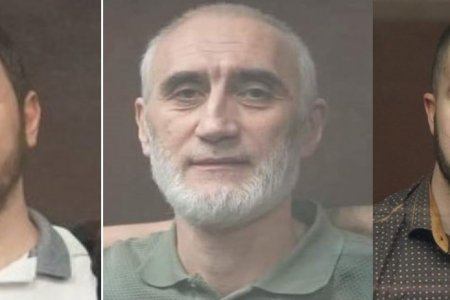

Oleh Fedorov (b. 1970) is a successful businessman. He played an active role in the Bakhchysarai Crimean Tatar community, and, as the number of political prisoners mounted, he attended many politically motivated court hearings and took part in information campaigns and flash-mobs in support of political prisoners. He was also active in providing material aid to the families of political prisoners. His younger daughter recently married the son of Remzi Memetov, another political prisoner.

Ernest Ibragimov (b. 1980) is the third Crimean Tatar political prisoner who earlier worked (as chef) for the renowned Salachik Cultural and Ethnographic Café. The café faced constant searches and harassment under Russian occupation and was finally forced to close in 2018. Fellow chef, Remzi Memetov was arrested in May 2016, while the café’s founder and civic journalist, Marlen (Suleiman) Asanov was arrested in October 2017. While taking part in flash-mobs, etc. in support of political prisoners, Ibragimov, who himself has four young children, was particularly active in the Crimean Childhood initiative. The latter arose in response to the ever-mounting number of children whose fathers have been imprisoned on politically-motivated charges

Like the eight men arrested earlier, Oleh Fedorov and Ernest Ibragimov are recognized by the renowned (and recently forcibly dissolved) Memorial Human Rights Centre as political prisoners.

See excerpts from Oleh Fedorov’s powerful final address to the court here: