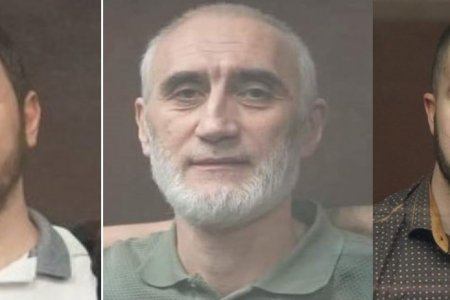

A Russian court has passed 13-year sentences against two Crimean Tatars who actively spoke out against repression in occupied Crimea and helped political prisoners and their families. Neither man was accused of any recognizable crime and the prosecution’s case was essentially based on conversations about religion four years ago, in which one of the defendants did not take part.

Oleh (Ali) Fedorov (b. 1970) and Ernest Ibragimov (b. 1980) were convicted on 8 July of ‘involvement’ in an organization which Russia has declared ‘terrorist’ (Article 205.5 § 1 of Russia’s criminal code, and with ‘planning a violent seizure of power and change in Russia’s constitutional order” (Article 278) Presiding judge Viktor Alexeevich Kostin, together with Roman Konstantinovich Plisko and Aleksei Borisovich Sannikov sentenced them to 13 years’ imprisonment with the first 3.5 years in a prison, the worst of all Russia’s penal institutions, with the rest of the sentence in a harsh regime prison colony. The court also added a one-year term of (severely) restricted liberty, to follow the main sentence. The sentences were lower than those demanded by prosecutor Valery Kuznetsov, but still huge.

The charges that the two men faced may sound serious, but are, in fact, based solely on a flawed and secret ruling by the Russian Supreme Court in 2003 which named a number of organizations ‘terrorist’ including Hizb ut-Tahrir. The latter is a peaceful, transnational Muslim organization which is legal in Ukraine, and which is not known to have carried out any acts of terrorism anywhere. There are grounds for suspecting that Hizb ut-Tahrir was thus labelled ‘terrorist’ in order to forcibly send refugees seeking asylum from religious persecution back to Uzbekistan.

Russia has, since 2015, been using such ‘Hizb ut-Tahrir prosecutions’ against Crimean Tatar and other Ukrainian Muslims in occupied Crimea, with most of the men arrested and imprisoned being civic activists or journalists, most often from the Crimean Solidarity human rights initiative. One of the most shocking aspects of this particular ‘trial’ was that the indictment against Fedorov and Ernest Ibragimov had been copy-pasted from that against the first large group of civic activists and journalists whose arrests in October 2017 and May 2018 were internationally condemned as Russia’s attempt to crush human rights defenders. Four civic journalists – Marlen Asanov; Ernest Ametov; Timur Ibragimov and Seiran Saliyev, were arrested in October 2017, together with two civic activists Memet Belyalov and Server Zekiryaev. On 21 May 2018, Russia’s attempt to crush Crimean Solidarity became even more overt with the arrest of the movement’s Coordinator (and civic journalist) Server Mustafayev and Edem Smailov. All of the men, except Ernest Ametov, were sentenced on 16 September 2020 to huge terms of imprisonment, from 12 to 19 years, although the charges were fatally flawed, and real evidence, even of involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir, non-existent. There were fears from the beginning that the sole acquittal by the Russian Southern District Military Court in Rostov of Ernest Ametov was purely to imitate a real trial. These were effectively confirmed on 14 March 2022, when the Military Court of Appeal in Vlasikha (Moscow region) rejected the appeals against the seven convictions, and overturned Ametov’s acquittal. He is now imprisoned again, on the same flawed charges, with a new panel of ‘judges’ from the same Rostov ‘court’ beginning a rerun of the original judicial travesty.

The grotesque nature of these ‘terrorism’ charges is highlighted by the fact that Fedorov and Ernest Ibragimov were only arrested on 17 February 2021, although they faced identical charges to the eight men arrested in 2017 and 2018, although all of these arrests were based on the same innocuous discussions on religious and other topics in a Bakhchysarai mosque back in 2016 and January 2017. The FSB had thus been in possession of supposed ‘evidence’ against Fedorov and Ernest Ibragimov for over four years. Even the supposed ‘testimony’ of anonymous witnesses was four years old.

A key and damning difference between the earlier ‘trial’ is that Oleh Fedorov’s voice is not actually on the illicitly taped conversations which are presented as ‘proof’ of involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir. The FSB mixed him up with another man who has since been arrested himself, Ruslan Murasov. The latter has confirmed to Fedorov’s lawyers that it is his voice on the tapes in question, however the ‘court’ refused to allow him to give testimony and face questioning. This is just one of the many ways in which Russian ‘judges’ effectively work for the prosecution in such ‘trials’.

In all of these prosecutions, the FSB uses ‘expert assessments’ by individuals with no expert knowledge of the subject, but who can be relied upon to claim that this word or that sentiment ‘proves’ support for Hizb ut-Tahrir. During the trial of the eight civic activists and journalists, Dr Yelena Novozhilova, an independent and experienced forensic linguist, gave an absolutely damning assessment of the linguistic analysis produced by the two linguistic ‘experts’ - Yulia Fomina and Yelena Khazimulina, This was ignored by the earlier ‘judges’, and has presumably been disregarded here also.

The most egregious example of collaboration between the prosecution and court is, however, in the use of so-called secret or anonymous witnesses. The court invariably allows the use of such alleged ‘witnesses’, although there is not a shred of evidence that the individuals would be in danger if their identity were revealed. All such prosecutions hinge on ‘testimony’ which cannot be verified in any way. The ‘judges’ are well aware that these supposed anonymous witnesses are essentially working for the prosecution, as evidenced by the number of times they prevent the defence from asking questions which show the alleged ‘witnesses’ ignorance of anything but the ‘incriminating’ details which they always know off by heart. The ‘judges’ are equally unconcerned by such witnesses’ baffling ‘forgetfulness’ as to the most basic of details; by the contradictions in their testimony and by clear indications that they are consulting with somebody (probably an FSB officer) before answering many questions.

In this case, as in the earlier trial of the eight men, the identity of the two ‘secret witnesses’ is in fact known, with this making the judges’ behaviour even more reprehensible. Ernest Ibragimov recognized one of the men, by his manner of speech, as Narzulayev Salakhutdin, a man who was living in occupied Crimea without the proper documents and who categorically did not want to be forcibly returned to his native Uzbekistan. This very clearly gave the FSB leverage over him.

In early November, both Fedorov and Ibragimov recognized the first ‘secret witness’, under the pseudonym ‘Ismailov’, by his voice (and likely accent). Ibragimov identified him in court, stating that he had known him as ‘Kostya the Latvian’, although he had also been known as Konstantin Alexeyev. This individual’s real name appears to be Konstantin Tumarevich, and he too has taken part in several trials as a secret witness. Just like Salakhutdin, it is clear that Tumarevich was in a very vulnerable legal position, as a fugitive from justice in Latvia, without proper papers.

The only reason for the judges to abet the prosecution in retaining any secrecy about the identity of a man whom all of the defendants publicly recognize is that they show the prosecution’s case for what it is.

******************

Oleh Fedorov (b. 1970) is a successful businessman. He played an active role in the Bakhchysarai Crimean Tatar community, and, as the number of political prisoners mounted, he attended many politically motivated court hearings and took part in information campaigns and flash-mobs in support of political prisoners. He was also active in providing material aid to the families of political prisoners. His younger daughter recently married the son of Remzi Memetov, another political prisoner.

Ernest Ibragimov (b. 1980) is the third Crimean Tatar political prisoner who earlier worked (as chef) for the renowned Salachik Cultural and Ethnographic Café. The café faced constant searches and harassment under Russian occupation and was finally forced to close in 2018. Fellow chef, Remzi Memetov was arrested in May 2016, while the café’s founder and civic journalist, Marlen (Suleiman) Asanov was arrested in October 2017. While taking part in flash-mobs, etc. in support of political prisoners, Ibragimov, who himself has four young children, was particularly active in the Crimean Childhood initiative. The latter arose in response to the ever-mounting number of children whose fathers have been imprisoned on politically-motivated charges

Like the eight men arrested earlier, Oleh Fedorov and Ernest Ibragimov are recognized by the renowned (and recently forcibly dissolved) Memorial Human Rights Centre as political prisoners.

See excerpts from Oleh Fedorov’s powerful final address to the court here:

Please write to Oleh Fedorov and Ernest Ibragimov!

The letters tell them and Moscow that they are not forgotten and that Russia’s persecution and the fate of its victims are under scrutiny. The addresses below will almost certainly remain current until after appeal hearings. Letters need to be in Russian, handwritten, and on ‘safe’ subjects. If that is a problem, use the sample letter below (copying it by hand), perhaps adding a picture or photo. Do add a return address so that the men can answer.

Sample letter

Привет,

Желаю Вам здоровья, мужества и терпения, надеюсь на скорое освобождение. Простите, что мало пишу – мне трудно писать по-русски, но мы все о Вас помним.

[Hi. I wish you good health, courage and patience and hope that you will soon be released. I’m sorry that this letter is short – it’s hard for me to write in Russian., but you are not forgotten. ]

Oleh Fedorov

344022, Россия, Ростов-на-Дону, ул. Максима Горького, 219 СИЗО-1.

Фёдорову, Олегу Владимировичу, г.р. 1970

[In English: 344022 Russian Federation, Rostov on the Don, 219 Maxim Gorky St, SIZO-1

Fedorov, Oleg Vladimirovich, b. 1970

Ernest Ibragimov

344022, Россия, Ростов-на-Дону, ул. Максима Горького, 219 СИЗО-1.

Ибрагимову, Эрнесту Ильясовичу, г.р. 1980

[In English: 344022 Russian Federation, Rostov on the Don, 219 Maxim Gorky St, SIZO-1

Ibragimov, Ernest Ilyasovich, b. 1980

* pronounced, and therefore often written as, Fyodorov