Russia’s Supreme Court has upheld an 11-year sentence passed, without any crime, against Crimean Tatar scholar Vadym Bektemirov. In rejecting the defence’s cassation appeal on 13 June, the ‘judges’ ignored both the illegal nature of a ruling from 2003 which Russia is using as pretext for political persecution, and the evident fabrication of the ‘case’ against Bektemirov. It is four years since Bektemirov was first taken prisoner, and such denial of his right to a fair trial cannot be called a surprise. That, however, does not make it any the less shocking that the highest-ranking ‘judges’ of the Russian Federation are complicit in the persecution of a recognized political prisoner.

Bektemirov was represented by renowned human rights lawyer Emil Kurbedinov. He pointed out the fatal flaws in a 2003 Supreme Court ruling which forms the sole grounds for the persecution of Bektemirov and over 100 other Crimean Tatar and other Ukrainian Muslims. That ruling on 14 February 2003 declared a number of organizations to be ‘terrorist’, including the peaceful transnational Muslim organization Hizb ut-Tahrir. The ruling was passed behind closed doors without members of Hizb ut-Tahrir or human rights groups being informed of it until after any time frame for lodging a legal challenge had elapsed. Vitaly Ponomaryov, an analyst from the Memorial Human Rights Centre, believes that Hizb ut-Tahrir was probably included on the list for political reasons, with Russia seeking an excuse for forcibly returning refugees to Uzbekistan where they faced religious persecution for involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir. While parts of Hizb ut-Tahrir ideology are highly contentious, there was no evidence back in 2003, nor is there now, that members of the organization had committed acts of terrorism anywhere.

Kurbedinov points out that there was no explanation for the ruling and that, in accordance with current Russian legislation from 2006 to the present day, Hizb ut-Tahrir was not a ‘terrorist’ organization. “The FSB simply carry out political repression under the guise of the fight against terrorism, just arresting religious figures and activists and getting them imprisoned on long sentences.”

Russia’s FSB began using this 2003 ruling to fabricate ‘terrorism’ charges against Crimean Tatar and other Ukrainian Muslims in early 2015. At first this was probably just an easy way for the FSB to get promotion or bonuses for ‘good statistics on fighting terrorism’ (and possibly for targeting Crimean Tatars whose opposition to Russia’s occupation had particularly riled the Kremlin.) The first human rights defender, Emil-Usein Kuku, was arrested on ‘Hizb ut-Tahrir’ charges in February 2016, and by late 2017 the FSB were quite openly targeting civic journalists and activists, especially from the vital Crimean Solidarity human rights movement.

Russia’s use of ‘terrorism’ charges to persecute members of the Crimean Tatar human rights movement has received international condemnation. So too has its illegal use of Russian legislation on occupied territory and the methods used to fabricate ‘evidence’, including FSB-loyal ‘experts’ without any qualification and ‘anonymous witnesses’. All such violations of the right to a fair trial were seen in Bektemirov’s case. The ‘proof’ was provided by fake secret witnesses and by an illicitly taped conversation in which Bektemirov simply expressed his own opinion.

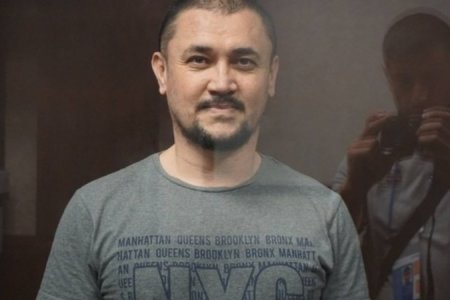

Vadym Bektemirov (b. 7.07.1981) has a higher education in Islamic Studies but worked as a translator to support his family. He has two daughters and a son, who was born after his arrest. Bektemirov also played an active role in the human rights movement which arose in response to mounting Russian repression. He regularly attended political trials of fellow Crimean Tatars; helped get parcels, with food and other essential items, to political prisoners held in Crimea or Russia, as well as organizing collective prayers for them and their families.

Such civic activism in defence of Russia’s victims has on many occasions led to the arrest of the civic journalist or activist, and on 7 July 2020, the FSB came for Bektemirov and six other Crimean Muslims.

Bektemirov was charged, under Article 205.5 § 2 of Russia’s criminal code with ‘involvement’ in an entirely unproven Hizb ut-Tahrir ‘cell’. The ‘evidence’ was essentially provided by two ‘anonymous witnesses’. These individuals may never have set eyes on Bektemirov, yet they were allowed to ‘testify’ in secret, claiming that from 2015 to 2018 Bektemirov had taken them to conspiratory meetings of the supposed Hizb ut-Tahrir group, recruited new followers; held explanatory discussions in mosques; and also discussed the persecution of Muslims in Crimea. Kurbedinov earlier stated that he believes one of these individuals to be Adnan Masri, and that he is appearing as a ‘secret witness’ not because he has anything to fear, but because he is, in fact, an FSB agent. Kurbedinov has amassed evidence demonstrating that Masri has played a similar role in at least five other ‘trials’, including those that resulted in huge sentences against recognized political prisoners Ruslan Zeytullaev and Enver Seitosmanov. There was also a video which, according to Kurbedinov, was illicitly made by an FSB agent in April 2015, in which Bektemirov essentially just expressed an opinion about Hizb ut-Tahrir.

The ‘trial’ took place at the notorious Southern District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don, with the prosecutor Sergei Aidinov, and ‘judges’ having all been involved in imprisoning other Ukrainian political prisoners. Presiding ‘judge Aleksei Abdulmazhitovich Magomadov, together with Kirill Nikolaevich Krivtsov and Sergei Fedorovich Yarosh effectively supported the prosecution by allowing secret witnesses and blocking questions from the defence proving the lack of any grounds for such secret ‘testimony or for the very charges themselves.

On 11 February 2022, these individuals handed down an 11-year sentence, one year less than that demanded by Aidinov, but with the first three years, as Aidinov had demanded, in a prison, the harshest of Russian penal institutions. That sentence was upheld on 3 April 2023 by ‘judge’ Dmitry Tepliuk from the Military court of appeal in Vlasikha (Moscow region) on 3 April 2023, and now, by Russia’s supreme court. Bektemirov is recognized as a political prisoner by, among others, the Memorial Support for Political Prisoners Project, which is categorical that he is being persecuted for his faith and civic position. His release, and that of Russia’s other Ukrainian political prisoners, has been demanded by the UN’s General Assembly, other international structures and organizations.