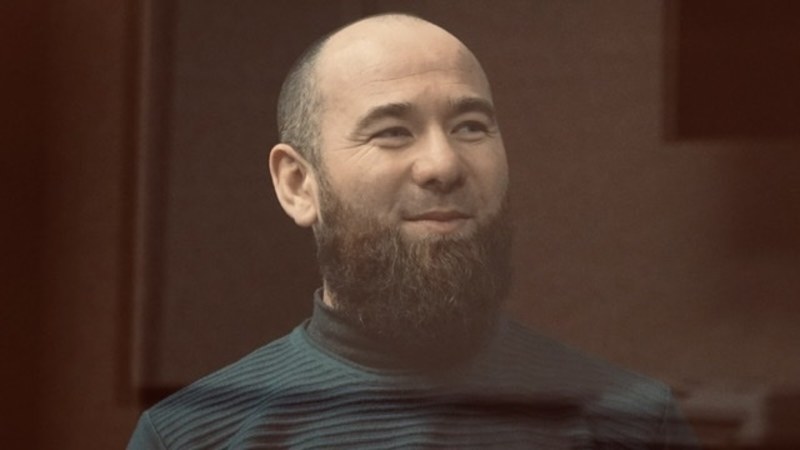

A court in Russia has sentenced Emil Ziyadinov to 17 years after a farcical ‘trial’ that made no pretence of trying to prove that the 37-year-old children’s sports trainer and Crimean Solidarity civic activist had committed anything but ‘thought crimes’. During one of the final hearings, Ziyadinov pointed out the absurdity of a situation where listening to poems, discussing political events in various countries and the reaction of international organizations to those events can get you accused of planning “violent seizure of power” with sentences worse than those passed on murderers. The methods used, he noted, mean that anybody can find themselves prosecuted and thrown into prison if they prove inconvenient to the regime. Such ‘inconvenience’ in occupied Crimea lies in ‘dissident’ religious and political views and, perhaps most importantly, civic activism in defence of political prisoners. Ziyadinov is one of over 80 Crimean Muslims, most of whom are Crimean Tatars, either serving or facing huge sentences on identical and profoundly flawed charges, backed by falsified ‘evidence’.

The flaws in the ‘case’ against Ziyadinov prompted the renowned Memorial Human Rights Centre to declare him a political prisoner back in July 2021, and are among the reasons why numerous international bodies have demanded that Russia release him and well over 100 other Ukrainian political prisoners.

All such demands, as well as the glaring flaws in the prosecution, were ignored by prosecutor Igor Vladimirovich Nadolinsky who claimed back in March that Ziyadinov’s ‘guilt’ had been proven and asked for a 17-year sentence. This was obligingly provided on 19 April by the panel of judges Stanislav Vladimirovich Zhidkov (presiding); Valery Sergeevich Opanasenko and Andrei Ivanovich Zarya from the notorious Southern District Military Court in Rostov (Russia). Ziyadinov was sentenced to 17 years in the harshest of Russian penal colonies, with the first four years in the very worst of such institutions (a prison). As has become standard in such sentences, a further 18 months of restriction of liberty was added after Ziyadinov’s release. The sentence will, of course, be appealed, however these are conveyor belt ‘trials’, with the ‘judges’ involved going through the motions of hearing a trial only to provide the sentences clearly expected of them. Since Russia began illegally applying its repressive legislation in occupied Crimea, there has been one occasion where the same court (but different judges) passed a sentence significantly lower than that demanded (against Ruslan Zeytullaev) and one ‘acquittal’ (of civic journalist and activist Ernes Ametov). The ‘trials’ of Zeytullaev were simply repeated until the FSB got the sentence it wanted, and the acquittal of Ametov was overturned. It seems likely that the so-called ‘acquittal’ was always a stunt to imitate ‘justice’ in a case obviously targeting civic journalists and activists.

Human beings are not conveyor belts, however, and Russia has shattered not only Ziyadinov’s life, but that of his wife and four young sons. Now 37, Ziyadinov had devoted a huge amount of time to bringing up his own children, while working as a children’s sports trainer. Despite the danger, he could not ignore the mounting repression under Russian occupation and joined the Crimean Solidarity human rights initiative, attending political trials, taking part in solitary pickets, etc. He did not stop, even after he faced harassment and administrative prosecution for supposedly ‘failing to obey enforcement officers’ by peacefully standing outside the home of Crimean Solidarity civic journalist Rustem Sheikhaliev during the latter’s arrest.

Russia’s FSB came for Ziyadinov during its ‘operation’ on 7 July 2020, when eleven armed searches were carried out and seven men arrested, including Oleksandr Sizikov, who is blind and walks with difficulty. All of the men, who included four civic activists, were charged with ‘involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir ‘,a peaceful Muslim organization which is legal in Ukraine, and which is not known to have committed any acts of terrorism or violence anywhere in the world. The highly secretive Russian Supreme Court’s ruling in 2003, which declared Hizb ut-Tahrir and many other organizations ‘terrorist’ was probably passed for political reasons, with Moscow looking for a way of forcibly sending Uzbek refugees back to Uzbekistan where they faced religious persecution.

Russia has been making arrests in occupied Crimea on the basis of that flawed ruling since January 2015, and has increasingly used these fake ‘terrorism’ charges as a weapon against Crimean Solidarity and human rights activists in general. In its statement, the Memorial Human Rights Centre indicated that Ziyadinov “is being persecuted for his non-violent exercising of his right to freedom of religion and of association. According to our information, he has been deprived of his liberty without any elements of a crime in order to stop his religious activities and also to crush the civic activism of residents of annexed Crimea.”

Ziyadinov faced the more serious charge of ‘organizing a Hizb ut-Tahrir group’ (under Article 205.5 § 1 of Russia’s criminal code). It has also become standard in occupied Crimea to charge all these political prisoners under Articles 30 and 278 – with planning an armed uprising. There has not been one case where ‘searches’ have found any weapons, etc, nor where any evidence has been provided of even the vaguest of plans.

Memorial HRC subjected the ‘evidence’ to analysis and was scathing in its conclusions. There were supposed ‘expert assessments’ of the transcripts of four meetings between Ziyadinov and an unidentified person. The alleged ‘experts’ claim that Ziyadinov is behaving like “a teacher”, “a mentor”, etc., while the unidentified person purportedly behaves like “a student”. The two men read what are asserted to be “texts from the ideological sources of Hizb ut-Tahrir “ and discussed them. “According to the investigators, this constitutes ‘terrorist activities’, Memorial noted and reiterated its long-standing position, that the Supreme Court ruling declaring Hizb ut-Tahrir ‘terrorist’ was unwarranted and illegal, and provided no proof of any terrorist activities.

Such ‘trials’ are especially shocking in occupied Crimea, given that Hizb ut-Tahrir is perfectly legal in Ukraine, and that Russia is in breach of international law (the Fourth Geneva Convention, for example) in applying Russian legislation on occupied territory.

Like most of the Crimean Tatars imprisoned on these charges, Emil Ziyadinov was born in exile (as a result of Stalin’s 1944 Deportation of the entire Crimean Tatar people). A graduate of the Taurida National University, he originally worked as a sports trainer, however had, in 2018, completed professional studies and become a qualified electrician.

Ziyadinov is now, yet again, exile, in Russia, very far from his wife and four small sons (Asadullakh, b. 2011; Umar, b. 2013; Davud, b. 2014; and Mukhammad, born in 2018. The children were, exceptionally, allowed to see their father, but only through the Russian ‘aquarium’ (effective cage) that Ziyadinov, who was not accused of any recognizable crime, has been held in at each court hearing.

Please write to Emil Ziyadinov!

The letters tell him and Moscow that he is not forgotten and that Russia’s treatment of him is under close scrutiny. Letters need to be in Russian, and on ‘safe’ subjects. If that is a problem, use the sample letter below (copying it by hand), perhaps adding a picture or photo. Do add a return address so that he can answer.

Sample letter

Здравствуйте,

Желаю Вам здоровья, мужества и терпения, надеюсь на скорое освобождение. Простите, что мало пишу – мне трудно писать по-русски, но мы все о Вас помним.

[Hi. I wish you good health, courage and patience and hope that you will soon be released. I’m sorry that this letter is short – it’s hard for me to write in Russian., but you are not forgotten. ]

Address

344022, Россия,, Ростовская обл., г. Ростов-на-Дону, ул. Максима Горького, 219, ФКУ СИЗО-1

Зиядинову, Эмилю Исмаиловичу, 1984 г.р.

Or in English

344022 Russian Federation, Rostov on the Don, 219 Maxim Gorky St, SIZO-1

Ziyadinov, Emil Ismailovich, b. 1984