When Russia’s aggression against Ukraine began in 2014, I lived in the city of Novoazovsk. Then, I learned about children from a disbanded boarding school who remained in the occupied territory. They lived in families that were unable to support them.

I told this story to my journalist friends in Kyiv. One of them, my close friend Olha Musafyrova, came to Novoazovsk. Despite the partial occupation of the city, Olha was able to visit and bring New Year’s toys for the children.

We visited these children, saw them, and realized we could not leave them. It was decided that I would remain in the occupation zone, and Olya in Kyiv, among friends and acquaintances, would collect things and send them to me, and I would pick them up across the demarcation line and give them to the children. Among the parcels were postcards signed in Ukrainian and Ukrainian books.

I wanted to convey to the children that they are citizens of Ukraine, that this is our country, and Ukraine has not forgotten about them.

When I went to Mariupol across the demarcation line to pick up parcels, I also tried to support our soldiers who were defending the city. I wanted to show them that people in the occupied territories were waiting for liberation.

When I was given a Ukrainian flag signed by the Lviv battalion with wishes to the patriots of Novoazovsk, this became the highest award for me. I was able to keep this flag, and it is still hidden in a very safe place in Novoazovsk. This will be my incentive to live until the liberation of all our territories and my city.

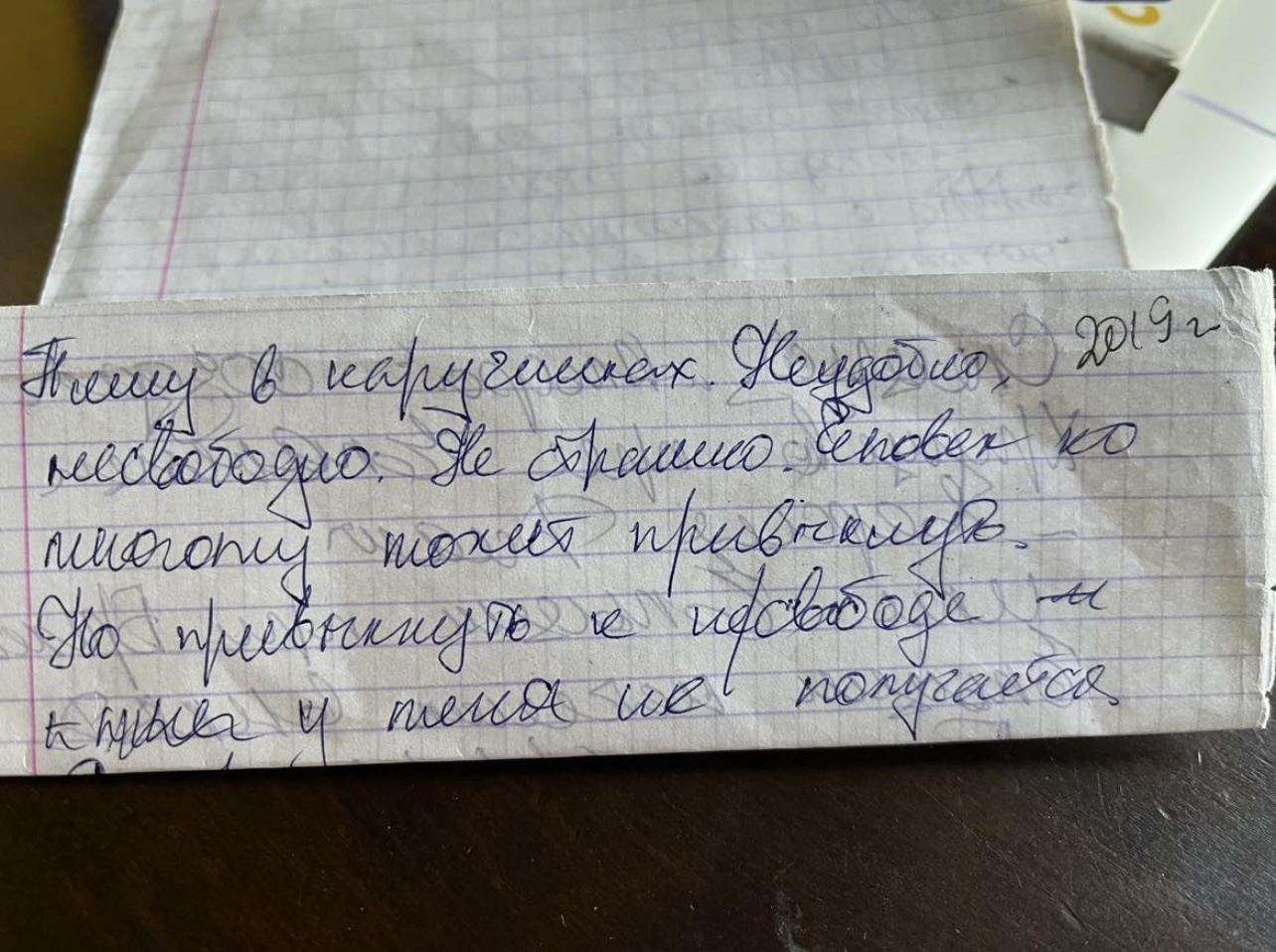

In 2019, I was arrested near my home. In the evening, with a bag over my head and in handcuffs, I was taken to an unknown location. Then they threw me into a cell where a girl told me that this was “Izolyatsia” — a Russian torture center in Donetsk.

It was a shock. I heard people screaming and understood that the same thing could happen to me at any moment.

I spent 50 days in this nightmare. There were different things there. I do not want to go into details because these memories are very traumatic.

The general conditions were as follows: you must stand from six in the morning until ten in the evening. You cannot sit down — any noise in the corridor, knocking, or opening of the feeder forces you to put a bag on your head and stand facing the wall. For the slightest offense, they beat you cruelly.

They can put you “in a glass” — a narrow stone room with a door, where you are forced to stand in the dark. You lose the sense of time. Constant threats, summonses for interrogations. On the second floor, there were barracks for their soldiers. They sometimes called men or girls for “entertainment” when returning from combat missions.

There was no sunlight — the windows were painted white, and bright lamps blinded the eyes. The basement was without proper conditions: a bucket instead of a toilet and one and a half liters of water daily. Once a day, they allowed you to take the bucket out. Otherwise, you sleep next to it and breathe all this. There was constant video surveillance. The guards were exclusively men, and they could undress you. You do not see them, but they see you.

I had a lawyer. It is a miracle that he was allowed to work with me. He said that my relatives submitted me for exchange immediately after I disappeared. He advised me to agree with everything the investigators say, sign, and not argue. They said the case would be quickly transferred to court, there would be a verdict, and an exchange would be possible.

The lawyer tried to transfer me to a pretrial detention center but warned that the conditions there would be harsh. Then I thought it couldn’t get any worse, but it turned out it could.

The cell in the pretrial detention center was tiny, but 20 women were in it. The two-story bunks were paired, and the toilet was a hole in the concrete floor. Almost all the women smoked, and it was hard to breathe. There were criminals there: women who committed murders, sold drugs or weapons, and fought on the side of Russia.

When they asked what article I was serving time under, and I answered that it was for extremism, they perceived me as “Ukrop” [literally “dill” is a Russian-language deriding term for Ukrainians.] They shouted, accused me, and said that because of people like me, Donbas was being bombed.

Women with tuberculosis, AIDS patients, and open purulent wounds slept with me on the bunks—the cell stank. Women smoked around the clock. There were fights, and some women used sharpened knives.

There was intense psychological pressure. They called it “working off”: if the investigator didn’t like something during interrogation, the prison authorities would give the order to the “overseer” in the cell to apply additional pressure. There was no medical care.

Once, I felt so bad that even my cellmates, who were hostile to me, rebelled and called the paramedic. He came but said: “What difference does it make when you die?” However, he injected me with something, and my cellmates gave me tea, and I gradually came back to life. Over three years, I wrote several times asking the investigator for permission to visit my family, but they refused.

In 2022, after a full-scale invasion, the attitude towards us worsened. The guards said: “So, “Ukropki”, are you waiting for an exchange? There will be no exchange. There is nowhere to exchange you. Kyiv no longer exists.” They banned parcels and even meetings with a lawyer.

Then, they decided to hold a so-called “referendum” on the annexation of the occupied territories to Russia. In prison, we were called to vote with one woman, who was also a political figure. We refused to go out, saying that we were citizens of Ukraine.

One of the guards, who treated us a little more humanely, came up to us and said: “Listen, this is an order — to beat you until you agree. Why do you need this?” We went anyway, and they led us one by one into a room. The prison lawyer was sitting there. On the table lay ballots already filled out for joining Russia. Behind me stood guards with truncheons.

I was told to put a tick in a specific place, but I wrote that I was against it. Surprised, The lawyer said to the guards, “Look what this “Ukropka” is doing.”

They beat me, threw me out of the room, and returned me to the cell. The woman who was with me did the same.

I told her: “You have a small child, you have a trial soon, maybe you shouldn’t have done this?” And she answered: “I wouldn’t respect myself if I had done otherwise."

In the whole prison, only four of us voted against it. It was me, my cellmate, and two women from another cell. I am proud of them but worried about their fate because they remained there.

After that, they threatened to transfer us to a Russian prison or reopen “Izolyatsia” and send us there.

The cell door opened on October 15, 2022, and they told me I had 20 minutes to get ready. I thought that now they would carry out all their threats. The woman from my cell, Olya, somehow sensed that it was an exchange and said, “So that’s how it happens.” She started crying and asked us not to forget about them. It was an exchange. It lasted for two days. There were 14 of us: 8 soldiers and 6 civilians. They covered our eyes with tape, tied our hands, and loaded us into a large military truck. We couldn’t see anything.

When they dropped us off, they took the tape off. We realized that we were back in the Donetsk pretrial detention center. They started laughing and said that they would shoot us.

Then they blindfolded us again, put us in a car, and drove for a long time. We heard one of the escorts say, “Relax, you’re on Russian territory.” This scared us even more.

They brought us to a military airfield. We spent the night right in the car, and they made us board a plane the following day. On the plane, we sat on the floor close to each other, unable to move. When we landed, they loaded us into another car. The girls saw through a hole in the tarpaulin that we were entering the Zaporizhia region.

When they dropped us off, we saw a man with a white flag. We were directed to him. It was an exchange. I barely remember this journey. A broken bridge, climbs, descents... But when we got there, I realized this is freedom, and we are saved.

After my dismissal, I learned that I had been awarded a prize in absentia for my contribution to protecting human rights. I received this award after I was free.

My main goal now is to help those who remain in captivity. I will always remember the words of my cellmate Olya: “Just don’t forget about us.”

In the occupied territories, people are still being taken away accused of espionage, extremism, and terrorism. This does not stop. If we remain silent, these people will stay in captivity for years. We won’t even know where they are. We can’t remain silent. Information reaches the prisons. When prisoners learn that they are remembered, it gives them the strength to fight. Oblivion is worse than death.

On December 6, 2024, the NGO “Numo, Sisters” was registered, headed by Liudmyla Huseinova. The organization unites women who, during captivity under occupation, survived CNSC (conflict-related sexual violence), torture, and other consequences of war.