Russia’s State Duma has passed in its first reading a draft law that dangerously extends the scope of Russia’s repressive legislation on so-called ‘extremism’. This legislation has already been used to persecute Ukrainians in occupied Crimea for their religious beliefs or for expressing their opinion, and Russia would doubtless seek to expand its application to any Ukrainian territory which it is presently occupying.

The bill was first tabled in the Duma in late July, with the first reading on 28 September. Although there were voices against it, it received a huge majority, with 278 for it and 54 against (and 16 abstaining. In light of that, as well as the general tendency towards ever more repressive legislation in today’s Russia, it seems likely to soon be adopted in full.

The bill extends criminal liability under Article 280 of Russia’s criminal code (‘calls to extremism’) to include similar liability for what is termed “public propaganda of extremism and its justification”. Russia’s legislation on ‘extremism’ has long been criticised as dangerously broad, enabling its application for expressing views that contradict the official position. It has also been used as a direct instrument of persecution. In banning the Jehovah’s Witnesses, for example, Russia’s prosecutor general and supreme court claimed that this huge world faith is ‘an extremist organization’.

The new bill does not in any way improve this situation. Instead, it adds two more terms that lend themselves to abuse. Definition of sorts is provided. ‘Propaganda of extremism’ is, for example, to extend to “information aimed at forming in somebody the ideology of extremism and conviction about its attractiveness.’ ‘Justification’ is considered to be “a public statement on recognising the ideology and practice of extremism correct, needing to be supported and emulated.”

Those who opposed the bill pointed, for example, to the broad scope of the legislation already, and the fact that this would make it broader still, or lead to it being used very selectively. For a bill which, if passed, would mean that Russians or Ukrainians on occupied territory could face up to five years’ imprisonment

As with the essentially analogous legislation on so-called ‘terrorism’, the person will be added to Russia’s notorious list of terrorists and extremists as soon as the criminal proceedings are initiated. Inclusion on that list leads to very practical difficulties, including the blocking of a person’s bank account.

Eva Levenberg, a lawyer from the OVD-Info human rights monitoring initiative, called the move “yet another step towards the effective blurring of the distinction between the concepts of ‘extremism’ and ‘terrorism’, with this confirmed by the bill’s explanatory note. Application of Article 205.2 of Russia’s criminal code [‘Public calls to carry out terrorist actions; public justification of terrorism, or propaganda of terrorism’]. She went on to explain that the charge is often applied over utterances, even if these carry an opposite meaning, if some word typical for application of these articles is used.

One of the authors of this bill is Vasily Piskarev, the head of the Duma committee on security. He claims that the amendments are needed because of the supposed propaganda of mass killings in educational establishments and kindergartens. Even if there is evidence that such actions are being justified or presented on the Internet as ‘fashionable’, that hardly warrants the dangerous extension to already repressive legislation.

There are already examples of abuse of the analogous article applying to so-called ‘terrorism’. In July 2020, a Russian court found Russian journalist Svetlana Prokopyeva guilty of ‘‘“public incitement to terrorist activity, public justification or propaganda of terrorism.”. This was based solely on comments she made after 17-year-old Mikhail Zhlobytsky blew himself up at the entrance to the Akhangelsk FSB offices on 31 October 2018. He had left a statement on a anarchist Telegram page saying that this was an act of protest because the FSB “fabricate criminal prosecutions and torture people”. Prokopyeva had published an article in which she was critical of the brutal system under Russian president Vladimir Putin and tried to understand the tragedy, while in no way condoning the young lad’s actions.

Even more cynical have been threats of criminal proceedings or actual charges of ‘justification of terrorism’ against civic activists for peaceful protest over the political persecution of Crimean Tatar or other Ukrainian political prisoners.

The argument is that, by defending a person who has been convicted on ‘terrorist charges’, the person is, himself or herself, justifying ‘terrorism’. That would always depend on what they actually said, but the argument is even more fundamentally flawed since prosecution on ‘terrorist charges’ is not, in Russia or occupied Crimea synonymous with actual terrorism. Russia has, for example, imprisoned over 100 Crimean Tatars, most of them civic journalists or activists on unproven charges of involvement in the peaceful Hizb ut-Tahrir. That organization is legal in Ukraine and most countries, and Russia’s supreme court has never explained why, in very secretive mode, it declared it ‘terrorist’ back in February 2003.

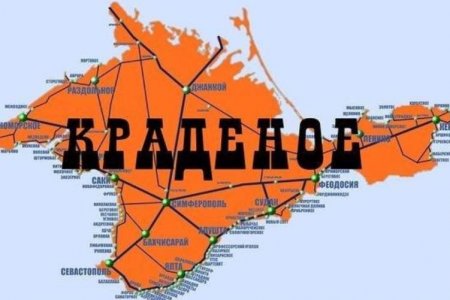

Anyone can, in occupied Crimea or Russia, be accused of ‘justifying terrorism’ by speaking out in defence of such political prisoners. If the bill on extending the ‘extremism’ legislation is adopted, the same will also be true here. Definition of ‘extremism’ has been loose from the outset and was stretched beyond any possible limits in Russia’s recent farcical imitation of a ‘trial’ to massively lengthen Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s imprisonment. It can, and almost certainly will, be used to justify application of ‘extremism legislation’ against those who rightly suggest that Russia’s occupation of Ukrainian territory is wrong and should end. This can be treated as ‘calls to change Russia’s constitutional order’, with the person then prosecuted for ‘extremism’.

The law could also be used to silence protest over the rising number of Ukrainians prosecuted and sentenced to 6 or 7 years’ imprisonment for practising their faith as Jehovah’s Witnesses.