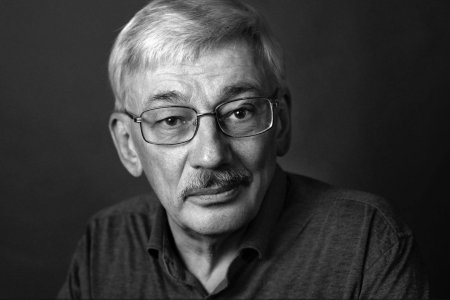

Russia’s public prosecutor has appealed against the hefty fine imposed upon Oleg Orlov for his criticism of Russia’s war against Ukraine, claiming this to be ‘too lenient’ and demanding instead that the 70-year-old Co-Chair of Memorial be imprisoned for three years (the maximum sentence possible). Since the prosecutor had herself earlier sought a fine, albeit a larger one, the suspicion arises that the initial sentence was always intended to be a temporary measure, possibly to deflect public attention from a high-profile trial.

The Memorial Centre for Human Rights Project (as they have been known since the Memorial Society and Memorial Human Rights Centre were forcibly dissolved) reported on 27 October that both Orlov and the prosecution had filed appeals against the 11 October ruling. In Orlov’s case, this was over the conviction itself, not the fine of 150 thousand roubles (around 1400 euros) which was far less than the feared prison sentence. Although judge Kristina Kostryukova from the Golovinsky district court in Moscow set the fine at 100 thousand roubles less than that demanded by prosecutors Svetlana Kildysheva and M. I. Shcherbakova, and ignored the request to order a ‘psychiatric assessment’, she did still find Orlov ‘guilty’ of a repeat case of ‘discrediting Russia’s armed forces’ (under Article 280.3 § 1 of Russia’s criminal code). This was a politically motivated verdict in a political trial on one of the charges which were hastily introduced within days of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine as a weapon for silencing protest.

The prosecutor’s office appeal, signed by N. V. Stupkin, seeks to justify the harshest possible sentence under Article 280.3 as being because Orlov purportedly “feels political and ideological hatred towards the Russian Federation”, and alleges that both Orlov and Memorial are “continuing to undermine the stability of civil society.”

The prosecution claims that the sentence was excessively lenient and is not commensurate with “the nature and level of public danger of what was done, and Orlov’s personality”.

Stupkin asserts that the court had failed to consider the aims of punishment, namely “to reform the convicted person and to avert new crimes”.

Orlov is alleged to have tried to convey his supposed “political and ideological hatred of the Russian Federation to as large a number of people as possible”, with this purportedly demonstrated by the nature and content of his publications on the Internet.

Memorial notes that the prosecutor not only mentions the two administrative prosecutions (under an analogous administrative charge of ‘discrediting the Russian armed forces’) but also throws in Chechen leader Ramsan Kadyrov’s attempt to sue Orlov for supposed ‘slander’ in 2009. This was after Orlov expressed what many others believed, blaming Kadyrov for the murder of Natalia Estemirova. The prosecutor even points out that Orlov was acquitted, yet still goes on to say that “the court established the fact of Orlov’s public pronouncements over the murder of Estemirova and the accusation over this by the head of Chechnya R.A. Kadyrov”/

All of this is claimed to demonstrate “Orlov’s persistent unlawful behaviour aimed at inciting hatred towards Russian political figures and bodies of state power.” Stupkin then goes on to accuse both Orlov and Memorial of “undermining the stability of civil society”.

“Under such circumstances”, this extraordinary document claims, “it is clear that Orlov, for his own reform, needs to be isolated from society.”

In response, Orlov point out that the question of whether this was a political trial had frequently arisen during the hearings. Now the prosecutor had produced an appeal that effectively exposed the political nature. The actual charge, of ‘discrediting the armed forces’ had been forgotten, with the prosecutor concentrating purely on the unacceptability of criticizing the regime.

“I am being persecuted for dissident thinking. And in the prosecutor’s view, the fact that I have not gone silent, and am continuing to uphold the human rights guaranteed by the constitution should be viewed as an aggravating circumstance”, Orlov notes.

Russia has been using both the administrative and the criminal charges of so-called ‘discrediting of the Russian armed forces’ to prosecute people, both in Russia and in occupied Crimea, for expressing opposition to its full-scale invasion, or even for demonstrating a Ukrainian flag, or playing a Ukrainian patriotic song. Even worse sentences are envisaged for what are claimed to be ‘fake information’ about the war, with this referring to fully documented facts of Russia’s war crimes in Ukraine, since these do not correspond to the lies told by the Kremlin and Russia’s defence ministry.

It has been clear from the outset that these charges are an attack not only on the veteran human rights defender, but on Memorial itself. The charges against Orlov were first announced on 21 March 2023, after mass raids that day on the offices and homes of several Memorial members. That attack came a little over a year after Russia forcibly dissolved International Memorial and the Memorial Human Rights Centre, and almost exactly three months after Memorial became laureate of the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize, together with Ukraine’s Centre for Civil Liberties and the Belarusian Viasna Human Rights Centre and its imprisoned head, Ales Bialiatski.

The criminal charges (under Article 280.3, because there had already been two administrative prosecutions) were over the posting on Orlov’s Facebook page of the Russian translation of his article “They wanted fascism. They got it”, which was published by the French Mediapart on 14 November 2022. The article states, for example, that “The bloody war launched by Putin in Ukraine is not only the mass killing of people, the destruction of infrastructure, of the economy, of cultural sites of this wonderful country. It is not only the crushing of the foundations of international law. It is also the gravest of blows against Russia’s future. A country which, 30 years ago, moved from communist totalitarianism has descended back into totalitarianism, but now fascist.”