![Українські слідчі відкрили тисячі справ за виправдовування агресії та глорифікацію її учасників. Ілюстрація: Марія Крикуненко / Харківська правозахисна група [стаття 436-2 кку виправдовування російської агресії] Thousands of criminal proceedings have been initiated on charges of justifying Russian aggression or glorifying those taking part in it Illustration Maria Krykunenko, KHPG](https://khpg.org/files/img/1608819125.png)

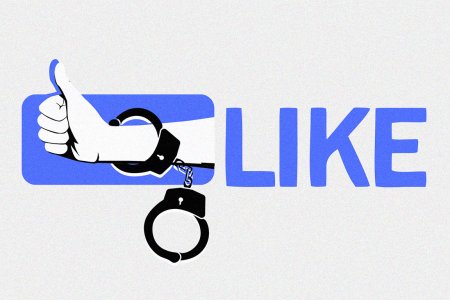

A recent five-year sentence against a Ukrainian pensioner for ‘liking’ texts justifying Russia’s war against Ukraine on the social network Odnoklassniki received wide publicity back in September 2023, with some commentators expressing deep unease. Mykola Komarovsky and Denys Volokha from the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group [KHPG] recently carried out a study which found a considerable number of similar sentences since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Their analysis is not aimed at criticizing new legislation introduced in response to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine but does highlight certain concerns about how criminal proceedings are being initiated and the response of courts throughout Ukraine.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine began in 2014, and the new article of the criminal code introducing liability for justification of Russia’s armed aggression against Ukraine was first proposed in early 2021. Russia’s full-scale invasion on 24 February meant that the entire country was at war and the new Article 436-2 was adopted by the Verkhovna Rada on 3 March 2022 and came into force on 16 March. This punishes for justifying Russia’s armed aggression against Ukraine, claiming it to be legitimate, denying it and / or glorifying those taking part in it. Such justification would also, of course, include claiming that the temporary occupation of Ukrainian territory was justified or denial that Russia is an occupying power. Certain aspects of the new article were criticized shortly after it came into force by, among others, Professor Mykola Khavroniuk from the Centre for Political and Legal Reform. The KHPG report notes that the new article envisages up to eight years’ imprisonment, yet does not provide a clear definition, for example, of what is to be considered ‘glorification’ or ‘justification of aggression’.

This obviously makes it difficult for an ordinary citizen to foresee what actions carry criminal liability. Without unambiguous definitions, particular verdicts are dangerously dependent on what a specific linguistic expert considers to be ‘justification’ or ‘glorification’, and on the individual court, In one case, for example, the expert’s argument for saying that a repost denied Russian occupation of Donbas seemed based on the fact that the post referred to the Russian proxy ‘Donetsk and Luhansk people’s republics’, without inverted commas and without any other indication that these refer to illegally occupied parts of Ukraine.

It is evident also from the report’s analysis of 715 court verdicts passed under Article 436-2 from 8 April 2022 to 26 September 2023 that there are huge variations in the sentences passed. Although the sentences passed in 674 of the verdicts were to terms of imprisonment from 2 to 5 years, the overwhelming majority of these (595) were suspended sentences. KHPG notes that the accused often reached an agreement with the prosecution and admitted guilt, with this presumably the reason that they did not face real terms of imprisonment. In at least one case, the judge insisted on a real sentence on the grounds that there were grounds for doubting the sincerity of the defendant’s stated repentance.

There were, however, also a few cases where, instead of terms of imprisonment; fines or community work, a court ordered that a person read certain books (aimed at refuting the propaganda over which they were being prosecuted).

One woman was sentenced to 8 years over a large number of videos posted on Tik Tok. She had, however, also been charged under Article 109 §2 and §3 of Ukraine’s Criminal Code (public calls to violently overthrow the constitutional order or seize power or circulating material with such calls).

429 out of the 715 cases involved reposts, etc. on Odnoklassniki. This is one of two networks, together with VKontakte, which were banned in Ukraine in 2017 because of their part in Russia’s information war against Ukraine.

It was the case of a pensioner from Pryluki in Chernihiv oblast sentenced on 6 September 2023 to 5 years for ‘likes’ on Odnoklassniki that gained most attention and criticism, for example, from human rights lawyer Volodymyr Yavorsky, In fact, however, Komarovsky and Volokha have identified several such cases, albeit with varying sentences.

The logic to such prosecutions is that, specifically on Odnoklassniki, if a person clicks the relevant ‘like’ option, then what they have ‘liked’ gets circulated on their profile and to all their contacts. ‘Liking’ is thus considered equivalent to circulating’, with it largely being immaterial how many contacts any specific person clicking ‘like’ has.

While the Pryluki ruling does not make it clear what exactly the person ‘liked’ (and therefore, according to the court, circulated), in other cases, the material in question is quoted. For example, on 2 May 2023, the Leninsky District Court in Kirovohrad sentenced a person to three years imprisonment over several such ‘likes’. One of the ‘likes’, for example, was in connection with a claim that the attack on the Kramatorsk Railway Station on 8 April 2022 had been carried out by Ukraine’s Armed Forces. There is widespread acknowledgement that Russia was behind the attack. In a report published in February 2023, Human Rights Watch concluded that Russia’s culpability was “strongly indicated” and that cluster munitions had been used on a station where hundreds of people had been trying to get on evacuation trains.

Worth noting that Ukraine’s efforts to combat Russian disinformation during the first years of its invasion constantly ran up against cries that this was a violation of freedom of speech. The argument from many defenders of such a position was that lies should simply be confronted by other texts telling the truth. The problem, however, should now be apparent to all. In Russia, and in all occupied parts of Ukraine, people face a likely prison sentence if they write the truth, even on social media, about Russia’s war crimes in Ukraine. Russia is also expending vast amounts on propaganda, with this aimed, among other things, at entirely rewriting even the events following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Ukrainian children in occupied Mariupol or Crimea are being told that it was somehow Ukraine’s Armed Forces who bombed Mariupol’s Drama Theatre and maternity hospital, and not Russia. Although western countries reacted to the full-scale invasion by finally banning certain Russian propaganda outlets aimed at foreign audiences, disinformation remains widespread and, often frighteningly effective at distorting the truth. Social media play a huge role in these with only the most egregious lies caught (or not).

The KHPG report notes some very strange cases. The authors, for example, found four verdicts where people had been sentenced for ‘liking’ an alleged quote by Nadiya Savchenko, the former military pilot whom Russia imprisoned and staged a show trial over. There is, in fact, no proof that Savchenko even said what is attributed to her, nor is it easy to understand how circulating this likely fake would fall under Article 436-2.

Ukrainian courts also handed down sentences over reposted reading or video material on other social media or platforms: Telegram (42); VKontakte (36); Facebook (33); Viber (11); YouTube (6); WhatsApp (3) and Instagram (3).

Some of the sentences had nothing to do with ‘likes’ or reposts on social media. On 6 September 2023, a physics lecturer received a one-year suspended sentence over comments made during a lecture by Zoom that were seen as justifying Russia’s aggreession. There were other prosecutions and sentences over conversations in the street, or similar.

There are, however, also some worrying occasions where the grounds for the prosecution could have only become known through unlawful interception of conversations or correspondence. The researchers found eleven cases where sentences had been passed over telephone conversations. They point out that the information about such conversations could only be obtained from one of the participants, or through covert investigative measures (wiretapping). Such covert operations are permitted only where a grave or especially grave crime is suspected, whereas Article 436-2 is classified as a minor crime. In one such case, before the Sosnivsky District Court in Cherkasy, a man was talking with his wife. Since she later brought the bail to get him released, it is probably safe to assume that she did not report his words, meaning that the conversation must have been tapped. The man, a pensioner, was sentenced on 17 May 2023 to two years, with this upheld by the court of appeal.

The majority of such disturbing cases were found in the Cherkasy oblast, with the authors of the report suggesting that the SBU [Ukraine’s Security Service] who were involved in the cases, were behind wiretapping carried out without lawful grounds.

In their conclusion, the authors of the report stress that their aim was merely to demonstrate the objective situation regarding the application of Article 436-2, not to assess whether it should exist, nor to judge whether sentences were proportionate.

They do, however, cite the latest UN Report on the Human Rights Situation in Ukraine (from 1 February to 31 July 2023). This notes that “the definition of the crimes for collaboration activities and for glorifying the armed aggression in national law overlaps with other crimes and would benefit from further clarity. This gives the prosecution a wide margin of discretion in the classification of offences. The severity of punishment for non-violent crimes also appears disproportionate to their gravity in some cases. For example, OHCHR documented the case of a 60-year-old woman who was charged with justification of the armed aggression and actions for the violent overthrowing of the State authority for her reposts on social media related to the ongoing war in Ukraine. She was sentenced to five years of imprisonment.”

Any question as to whether citizens could foresee what would lead to prosecution, as well as over the proportionality of the sentences could result in applications to the European Court of Human Rights which Ukraine would not necessarily win.