![Українські слідчі відкрили тисячі справ за виправдовування агресії та глорифікацію її учасників. Ілюстрація: Марія Крикуненко / Харківська правозахисна група [стаття 436-2 кку виправдовування російської агресії]](https://khpg.org/files/img/1608819125.png)

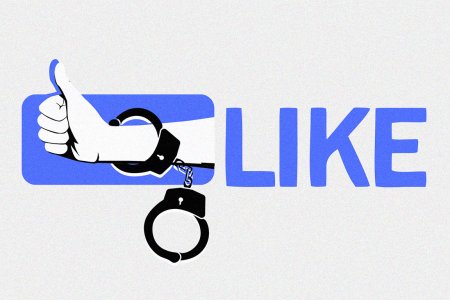

In early September, people in Ukraine began discussing the case of an older woman sentenced to five years in prison for liking a post on the Odnoklassniki (Classmates) social network very popular in the former USSR.

The court decided that liking the post was tantamount to justifying Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. According to the court ruling, “The said publication, due to the algorithm of the regular ‘like’ function in the Odnoklassniki social network, was automatically posted in the news feed of persons from the accused friends’ list (178 people).”

Imprisonment for liking or sharing posts, and sometimes even for talking on the street or the phone, is already quite common in Ukraine, although just this particular case has attracted general attention. In the court register, we found 715 verdicts under Article 436-2 of the Criminal Code, under which the woman was convicted.

The Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group analyzed all these sentences and found out what actions the Ukrainian courts consider “justification of the aggression of the Russian Federation and glorification of its participants,” imposing imprisonment for this.

Law and judicial practice

In March 2022, the Criminal Code of Ukraine was supplemented with a new Article 436-2 entitled “Justification, Recognition of Lawfulness, and Denial of the Armed Aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine, and Glorification of its Participants.”

This article provides for up to eight years in prison but does not clearly define what is meant by “glorification” or “justification of aggression.”

![© Денис Волоха/ХПГ [кримінальний кодекс]](https://khpg.org/files/img/1600326866.png)

At the time of writing, the Unified Register of Court Decisions under Article 436-2 contains 715 verdicts (we include here full court decisions and do not consider those that contain only the introductory and operative parts).

Most of these cases (429 verdicts) concerned disseminating “criminal” publications on one’s Odnoklassniki page. When a registered Odnoklassniki user clicks like (or “class” as it is called in this social network) under a post, this post is shared on their profile, and friends can see the post.

This is the basis for bringing such Odnoklassniki users to justice: The courts consider clicking a like on a social network equivalent to spreading information among friends. The more friends you have, the wider the circle of information recipients.

If the prosecution manages to prove that a post denies or justifies Russian aggression (a usual proof is an expert examination, to which we will return), then clicking the “like” button becomes a crime, and a person can be sent to prison for five years.

But don’t rush to clean up your social media friend lists, even if you’ve meant to do so for a long time. We found no correlation between the number of friends and the sentence under Article 436-2.

For example, the Leninsky District Court of Kirovohrad sentenced a person who had 524 social media friends and 118 followers to three years in prison.

The decision of the Terebovlyansky District Court of the Ternopil Region mentioned that the accused person had 256 friends, but the punishment was more severe — five years in prison.

In the case mentioned at the beginning, the woman had even fewer friends but was also sentenced to five years in prison.

Below, see the example of a post whose “like” can become a crime: (in Russian, a quote from the court decision) “The best news. Grandma and grandpa are alive. They were rescued by DPR and LPR militias and taken to Luhansk. My daughter and son-in-law flew from Barnaul. Now they are all in Barnaul. My grandparents invited me to Red Square on May 9.” The expert involved by the court stated that this post contains a denial of the temporary occupation of part of the territory of Ukraine, as it “refers to the so-called ’LPR’ and ’DPR’ as separate state entities.”

There was also a case when a man was convicted for liking an alleged quote by Nadiia Savchenko that “the war in Ukraine can be ended with ten tank shots at the Presidential Administration and the Verkhovna Rada.” There is no evidence that Savchenko said this. The court sentenced the man to two years in prison for clicking the “class” button under this post, as well as a video with undisclosed content. In at least three other court verdicts, people were punished for likes under this Savchenko fictitious quote.

Not only Odnoklassniki and not only social networks

People are also prosecuted for actions on other social networks and messengers, although much less frequently.

- Telegram — 42 sentences

- Vkontakte — 36 sentences

- Facebook — 33 sentences

- Viber — 11 sentences

- YouTube — six sentences

- WhatsApp — three sentences

- Instagram — three sentences

People are sometimes punished for private correspondence with their loved ones. Here is an excerpt from the verdict of the Shchorsky District Court of Chernihiv Region:

“On 24.06.2022 at 21:05, a person, being in the town of Snovsk, Koryukiv district, Chernihiv Region, using his account in the Telegram messenger, realizing the illegal nature of his intentions, being aware that the Russian Federation has been committing an act of armed aggression against Ukraine since 2014 and intending to justify these criminal actions of the Russian Federation and its military and political leadership, in correspondence with the contact ’Brother,’ posted a video by ’reposting’.”

Similarly, a man was prosecuted for chatting in WhatsApp chats according to a decision of the Zavodsky District Court of Mykolaiv. Moreover, since he justified the aggression twice (he sent the message twice with an interval of two days), he was prosecuted under parts 2 and 3 of Article 436-2, i.e., for a repeated crime.

Prison term for a phone call?

Out of the entire number of court decisions, eleven verdicts hold a person liable for talking on the phone.

For example, the decision of the Sosnivsky District Court of Cherkasy states that a man, while communicating with his wife, “justified the need for so-called ’denazification’ as one of the components of Russia’s armed aggression, since, in his words, Ukraine appears to be saturated with Banderites.” Ultimately, the wife had to post almost UAH 200,000 bail for her husband. Their communication “cost” the retired husband two years in prison: the court of appeal upheld the sentence. This decision was highlighted in the local news.

The method of obtaining evidence in such cases is of interest since there are only two ways to obtain information about a telephone conversation: Either through the testimony of the other party or through a “third ear,” in other words, through covert investigative actions.

However, such investigative actions should be preceded by an already initiated criminal investigation against a person, which is clearly not our case, not to mention that such covert investigative actions by the provisions of the Criminal Procedure Code (Article 246, Pt. 2) are allowed only concerning a severe or especially grave crime. The first part of Article 436-2 covers a minor crime, and it is impossible to immediately predict that a person’s actions have the elements of a crime under part 2 or 3.

The majority of such verdicts were handed down in the Cherkasy Region. Since the SBU was involved in the abovementioned and similar verdicts (the SBU department stored the phone and laptop seized from the suspect), the service seems to wiretap phones without legal grounds.

In several cases, the court prosecuted people for talking on the street. A resident of a village in the Sumy Region was punished for intervening in her fellow villagers conversation about the war in Ukraine and “started telling them that the President of Ukraine started the war, that Russia had legitimately invaded Ukraine, and that the government of Ukraine was to blame for everything.” After that, the woman repeatedly continued similar conversations with her fellow villagers, for which she was brought to justice.

Here is a quote from a similar decision of the Khmelnytsky City and District Court:

“The person is accused that on November 2, 2022, acting for ideological reasons to implement her criminal intent aimed at spreading her worldview among other persons, holding the position of a physical therapy nurse, while at her workplace in the physical therapy room located on the 0th floor of the clinic building, held a conversation with a Ukrainian citizen.”

The decision goes on to provide a detailed transcript of the nurse’s conversation, where she repeats various Russian propaganda theses and admits that she adores Russian propagandists Solovyov and Skabeyeva. Several other dialogues with other patients are also cited. The woman was sentenced to five years in prison, but due to a deal with the prosecutor’s office, she was released from serving her sentence.

Instead of prison — read the books!

Imprisonment (674 sentences) prevails among all types of punishment for justifying Russian aggression. The arrest (short-term imprisonment up to six months) was imposed in 13 cases, and correctional labor was imposed in five cases. Restriction of liberty was not imposed in any of the verdicts under study.

The most common term of imprisonment is five years, which was imposed in 229 verdicts. The second most common term — three years of imprisonment (203 verdicts).

In at least one case, a person was sentenced to eight years in prison with confiscation of all property. This was the decision of the Shevchenkivsky District Court in Kyiv, which sentenced the woman for disseminating information through her TikTok account. In 2022, she posted several videos: some were classified as justification of aggression, and some as actions aimed at violent change or overthrow of the constitutional order (Article 109 of the Criminal Code).

The judge of the Prymorsky District Court of Odesa ordered the accused person to read the books “Independent Ukraine” by Mykola Mikhnovsky, “Gates of Europe. The History of Ukraine from Scythian Wars to Independence” by Serhiy Plokhiy and “The Division of Russia” by Yuriy Lypa. The obligation to read books is found in three other verdicts of the Primorsky District Court.

The Cherkasy court assigned an even longer list of mandatory reading. The defendant was voicing pro-Russian opinions in telephone conversations. She did this during lunch breaks at her job at the Cherkasy Regional Prosecutor’s Office. The court ordered the civil servant to get the books from the Lesya Ukrainka Library in Cherkasy, make a handwritten summary of their contents of 3-5 A4 sheets long each, and show them to the probation officer.

Sometimes, courts have commuted a sentence to a fine following Article 69 of the Criminal Code, which allows for a lighter sentence than the law prescribes. There are only 13 such decisions in the court register. The largest fine found by KHPG was UAH 102000. An Odesa court imposed this penalty on a man who sent 658 messages via Telegram in two weeks. The expert found that all of these messages fell under the disposition of Article 436-2. The services of this expert cost UAH 15101, which the court also recovered from the accused.

In almost each such criminal case, a special linguistic examination was conducted. Article 436-2 itself does not define what is meant by terms like “justification,” “recognition of legitimacy,” and “denial” of Russian aggression or “glorification of its participants.” It is up to an expert to decide whether a particular social media post or statement can be qualified by these terms. The cost of such an examination is quite significant. In one of the cases, it amounted to UAH 56399, but there was also a case where the expert cost much less, only UAH 2,390 UAH. It is unclear why there was such a difference in the cost of expertise, as the cases were very similar. Usually, the court puts the cost of expert services on the convicted person.

![За проросійські висловлювання суд призначив до прочитання твори Ірини Вовк. Світлина: Бібліотека Запорізького державного медико-фармацевтичного університету [ірина вовк донецький аеропорт на щиті іловайськ книги книга]](https://khpg.org/files/img/1608819118.jpg)

In most cases, the court imposes imprisonment, but it also often releases the person from serving a sentence with a probationary period. In other words, the person does not end up behind bars but only covers court costs, is obliged to report to the local police station regularly, and experiences the stress of the criminal process.

In 595 out of 715 studied verdicts, the court released the convicted person from serving their sentence. Often, the defendant agrees to enter into a plea bargain with the investigation and admit their guilt. It seems that just a guilty plea is usually the reason for the court to release a person from actual imprisonment.

For example, the Vasylkivsky District Court of Dnipropetrovs’k Region decided that the accused could not be released from serving his sentence due to “the ongoing armed aggression against Ukraine by the Russian Federation, as well as the reasonable doubts about the sincerity of the accused’s contrition."

There were also cases when the appellate court sent a person to prison, although the court of first instance considered that they could be released. For example, the Dnipro Court of Appeal overturned a lower court’s verdict due to the “unjustified release of the accused from serving the sentence with probation.” It issued a new verdict, sending the person to serve the imprisonment sentence.

Transferring funds to support the Armed Forces is sometimes mentioned as a mitigating circumstance.

Thousands of cases concerning the justification of aggression

On the Prosecutor General’s Office website, anyone can find statistics on offenses by individual articles of the Criminal Code.

The relevant table for 2022 shows that a total of 1354 criminal offenses under Article 436-2 were registered. In 622 cases, a person was notified of suspicion. In 513 cases, the proceedings were sent to court, including 506 cases with the charge sheet. Article 436-2 was added to the Criminal Code only in March 2022. Thus, the information is available for April-December of this year.

The 2023 statistics at the time of writing were available for January— September. A total of 1,189 criminal offenses under article 436-2 were registered. In 613 cases, perpetrators were served with notices of suspicion. In 533 cases, the proceedings were sent to court, including 530 cases with the charge sheet.

Statistics of cases under Article 436-2 of the Criminal Code

|

2022 |

2023 |

|

|

Proceedings |

1354 |

1189 |

|

Suspicions |

622 |

613 |

|

Sentences |

290 |

425 |

During the same period (January— September) in 2023, for example, 1243 offenses under Article 368 (acceptance of an offer, promise or receipt of an undue benefit by an official) were registered. Almost the same number of robberies — 1378 — were registered.

Conclusion

From time to time, the Ukrainian media reports news of people being convicted for supporting Russian narratives online. The well-known case of sentencing a 60-year-old woman was also mentioned in the report on the human rights situation in Ukraine prepared by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. This report also notes that “in the Ukrainian legislation, the definitions of the crimes of collaboration and glorification of armed aggression overlap with the definitions of other crimes, so it would be helpful to clarify them. Such overlapping gives the prosecution a wide range of options in qualifying offenses."

This study aimed to show the objective situation with prosecutions under Article 436-2. We do not evaluate the appropriateness of this article and how proportionate the punishment is.

Our analysis shows that Ukrainian investigators are very active in opening proceedings on justifying Russian aggression against Ukraine. The vast majority of those sentenced to imprisonment were punished for their likes on the Odnoklassniki social network. Still, the accused mostly did not go to prison because they were released from serving their sentence. It seems that the mitigation of a conviction was directly related to whether a person admits guilt.

Sentences based on personal correspondence with relatives or telephone conversations are pretty disturbing: there is a possibility that the investigation is obtaining evidence violating a person’s right to privacy. This could eventually result in cases against Ukraine in the European Court of Human Rights.

In 2020, the KHPG director, Yevhen Zakharov, analyzed all decisions on crimes against national security. These studies are available on our website.

- Application practice of Article 109 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (Actions aimed at forceful change or overthrow of the constitutional order)

- Application practice of Article 110 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (Trespass against territorial integrity and inviolability of Ukraine)

- The practice of application of Article 111 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (High treason)

In March and April of 2022, new Articles 111-1 (collaborationism) and 111-2 (aiding the aggressor state) were added to the Criminal Code.

Data processing: Illia Ioffe; Illustrations: Mariia Krykunenko.